What is new media? Most of the time I don’t want to spend any more energy than I have to thinking about the question; it has a “what is art?” flavor I don’t care for. There are exceptions to this, though, and last weekend proved to be one of them.

Tackled during the “Issues of Digital Media Art” session at The Woodstock Digital Media Festival Saturday morning, panel moderator and artist Joe McKay began by asking why we always have to ask what new media is. Beyond providing a basic distinction between digital art (a digital print or sculpture — object based work) and New Media (work that is created, stored and distributed with digital technologies), the panelists addressed how the medium is defined in universities, by curators, and by artists (who often opt not to bother with the issue at all). Members also addressed the pull of technology to artists, a topic of conversation that led to Magda Sawon’s assertion that “we’re at this stage where the democratization of access to technology brings in a very different layer of artists who still could be called media artists, but for them it’s a natural tool.” For this new strata of artists, “It’s not a learned tool and discovered tool, it’s the available tool.”

Sawon was part of a panel consisting of herself and Tamas Banovich, owners of Postmasters art, Christiane Paul, curator of New Media at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and artists Marcin Ramocki and Mary Flanagan.

Joe McKay: [preamble] I am going to ask the first question, and after that we have a mic for you to ask questions. Here’s my question: what is new media art, and how do you define it for yourself? I also wanted to ask what it means that we always have to ask what new media is. We don’t go to a painting now and immediately ask “what is painting?”. Does the fact that we always have to ask this question mean that the term is becoming useless? Is it a successful term to describe what we’re doing?

Christiane Paul: The question has been discussed for at least fifteen years when it comes to media that use digital technologies. To the best of my knowledge, the term was first used in the early twentieth century for film. Everybody agrees that it’s a really bad term because it doesn’t say anything. Its big advantage is that it can accommodate whatever is happening at any given point, because this is an evolving medium. So some basic distinctions that need to be made: first of all, “new media” is often used interchangeably with “digital art.” There’s digital art that uses technologies as a tool in the creation of a photograph of a painting of a sculpture; it is a different aesthetic, but that doesn’t change presentation, selling, et cetera. We’re dealing with art objects. And then there is new media that is created, stored, distributed by the digital technologies, and that really makes use of the inherent characteristics of the medium: works that are interactive, generative, participatory. They don’t need to be, but those are the characteristics that are associated with the medium. And those pose tremendous challenges. But, the issue is that this is a constantly evolving medium, and we constantly have to keep defining it. Social media is something of the twenty-first century, like the whole facebook type of networking. Locative media only exploded really in the twenty-first century; the net art of the nineties is not the net art of the two thousands. So that’s why I think we have to keep asking that question. Fifty years ago people said the term is old, and we should make something new, and that is difficult and problematic. It hasn’t happened yet.

Magdelena Sawon: I can just mention that the progression of the new in art occurs in other mediums as well. I think you can trace the very same question to, say, “what is photography?” When that arrived on the scene, everybody was already familiar with painting. So these progressions of technologies- and what allow artists to create new forms of expression and new output- they just kind of continue, so it’s a big umbrella to call something “new media,” and then you have to compartmentalize into things more specific [terms]. But this progression from painting, photography, video and then we can take digital art, computer art, new media art, whatever- those are just the efforts of naming things. I don’t think creators think that way, that they’re going to name their forms.

Joe McKay: That was actually my follow-up question: does it come up in your practice? Because I find I’m only ever saying “new media” when I’m describing it, and never really when I’m thinking it.

Mary Flanagan: I agree with you. In my studio practice, when I’m making things, I cross the lines all the time. For instance, if something comes up in video art form in the process, does it necessarily mean that it’s a video art process, or does it mean that you’re following cinematic traditions? You follow your practice instead of titles about what that is, and sometimes you just have to describe them to others in encapsulated ways. And I think what’s interesting about new media art is also that the public hasn’t run into this kind of work before. Often the easiest way that I end up describing my work, even though it’s wrong- to total strangers, I say “it’s kind of like animation,” because it ends up with these more traditional areas. It’s hard to make associative links unless you’ve seen the dynamic nature of this medium in action.

Marcin Ramocki: Yea, about the naming thing- when you get a teaching job and have to put a name tag on your door [to indicate] what you’re teaching, so that’s when the decision happens. Mine is “computer graphics,” and I didn’t like that, because I felt I wasn’t teaching computer graphics, I was teaching a fine art discipline. And that’s when the need comes to name things.

I’d also like to mention that naming the discipline of art by the medium is kind of a modernist thing. It wasn’t always like that. It isn’t like surrealism or expressionism; there’s video art, there’s film art, there’s all these new technologies, but we threw them into this one bag and called them “new media,” and that’s really a modernist thing. It would make sense for it to end.

Christiane: I think it’s very different from practitioners, where they shouldn’t worry about categories, and taxonomies, but when you work within art institutions or academic departments, it’s a huge issue, and the question comes up constantly; I’ve answered it thousands of times. When I worked at the Whitney, I had to revise all the loan agreement forms because they weren’t specific to new media. The museum system databases that are being used have absolutely no way of accommodating any form of new media, and that’s where you constantly keep defining new media for me. It’s not happening on the practitioners’ end, it’s happening on the end of art history and institutions.

Tamas Banovich: I mean, how new can it be if there are institutions assigned to it? Personally, when I arrived in New York thirty years ago, I was coming from Eastern Europe with an art degree, and I just said, well, there’s nothing I can do. I said I have to get a job, and I picked up the New York Times personals, if you guys even know what personals are anymore- there used to be ads in that newspaper, in the back- and I opened it, and there were five hundred advertisements for artists, and I said “My God! I arrived in a New World- it’s artists, artists, artists.” And it turned out these were all really menial graphic design jobs. So I’m just saying that because you’re asking about naming, and what it means in different environments

Audience member: I’m really interested in hearing you all talk about the distinction between these two avenues- creating new media art or digital media art- I would imagine, particularly with the complex tools that are available today that an artist might be drawn to creating something because they want to express something, so they need to turn to these tools, or they’re drawn to it because they think the tools are cool, so they experiment with it and something comes out of it. So my either/or question is: what do you see the coolest, most groundbreaking stuff coming from? Is it the initial impulse, “there’s something I want to express, thank goodness I found the tools to do it[express myself],” or “these tools are so cool, wow, look what I did?”

Christiane: Well, the answer is both though I think everybody would agree that gratuitous use of technology is never the way to go;, to use something just because it’s cool and has a wow effect doesn’t lead anywhere. But there are artists who are interested in investigating the characteristics of anything new, and you can do that in a conceptually very interesting way, but what counts is the concept and the depth of it. That being said, you can still go both routes. And I know many practitioners who could fall into these categories, who are looking for the tools of expression and realize that paint they can not achieve this with painting I and need other technologies, are the; they are the ones who pick up new technologies and investigate them.

Tamas Banovich: I mean, old technologies like painting and sculpture, those are very intricate technologies- I wouldn’t say that you need more sophisticated skills for doing making digital art and really doing something sophisticated in those mediums with digital art. I remember when we started being becoming interested in digital art [in the late eighties], the main reason we rarely showed digital prints in color was because I could never decide whether it was gratuitous or whether it was actually used because the person had an urge to express something, and this is that was the best way.

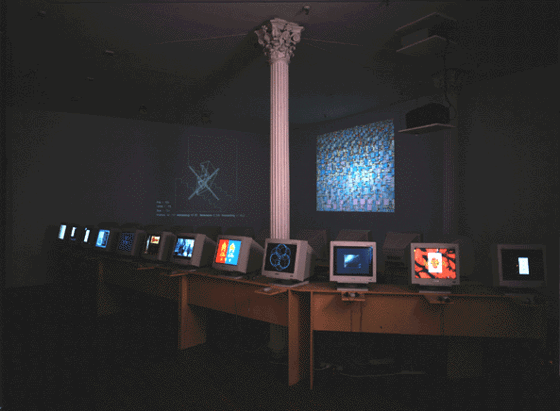

Magda: Well it always comes back to what’s the tool of production and what’s the medium of expression for the work that comes out. And what I would say that it can be established that there’s are two phases of new media that we experienced. We started in 1996 with this show that was called “Can You Digit?” and it was one of the first exhibitions where screen-based work was not lumped into a basement computer, but presented in a similar way to what how other artworks would be presented, each singularly presented on its own screen. We were trying to gauge the nature of what screen-based art was at that point. And it seemed to be a time when people were really digging into the medium itself, doing a lot of investigation, and creating their own software work. And just like how as media operates in communication, in and distribution. And recently I think we’re at this stage where the democratization of access to technology brings in a very different layer of artists who still could be called media artists, but for them it’s a natural tool. It’s not a learned tool and discovered tool, it’s the available tool.

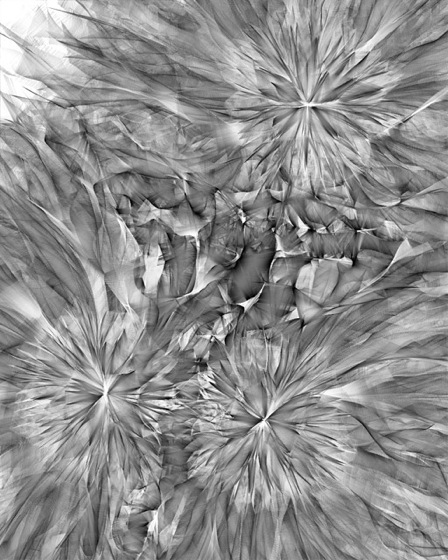

Marcin: I completely agree, in the nineties there was a stage where people were really into the technology and the softwares, looking into how things work and then they were just working out different ideas with the technology. But I wanted to mention that, in the nineties, there was a very important period that we shouldn’t forget: where artists who came from traditional media were looking for the first time into things like Photoshop and Director- many people may not remember that software but this was the time when artists were traditional artists, they were trained to paint, make prints, [and] they looked into writing software for the first time. And the way those tools were structured was very important, because lots of the art worked in response to the internal structures, how the software was put together- where tools existed in Photoshop, whatever functions existed in Director at the time. There’s this a whole wave of artwork that was in response to artists learning these technological tools. I think this is a very important stage.

Mary: I think one of the things that you’re seeing in the works that are in the festival and in a lot of contemporary digital work is this way in which we’re already engaged in digital culture. And digital art or new media art offers us a different way of seeing that engagement, and reflecting upon that engagement, and standing outside that engagement. There’s a celebratory nature; one can say, “wow, it’s so cool that it does that,” or we can use this critical perspective and say “ wow, look at this system, that this system makes me reflect on my own relationship to technology and my own relationship to that tool as a spectator of that art.” And so there’s that layer to it that I find really valuable. It’s something that at first we might not get about digital art if it’s doing something that’s difficult to understand; we’re very used to interfaces, things working for us at the touch of a button. Our technologies in everyday life are supposed to be easy, and often artists want to make them uneasy. Make them disturbing, have us reflect upon things that are going on, really break that seamless relationship we have to our technology in order so that we can see it and look at it. And ask questions about it.

Christiane: It’s certainly true that in the mid-nineties there were artists who were trained in other disciplines and came to the medium, but artists started working with digital technologies in the sixties. That’s when the first algarhythmic drawings were done, when they used punch cards, and later pen and pencil plotters to do drawings, and artists were writing software in the eighties and continued. So there have been many artists who have been working within the medium for decades and would also say, “yes, we’re becoming more and more immersed in this culture and familiar with it, but there’s always the next thing.” For example, amended reality, which is something that has been taking off only very recently — there’s again the same kind of rush and exploration of the medium- people jumping on it, people not sure what can be done, how it can be done, the technology being clunky, and we’re always repeating certain kinds of patterns with every software and, technology that comes along.

Thomas: To me the most exciting discovery of the time was that all those concepts, which were adopted when the technology was made possible, all those concepts were there before the technology;, the technology just made all those concepts viable., The most interesting discovery for me was that it wasn't technology-driven, it was concept-driven.

Paddy Johnson (from the audience): First, somebody from twitter asked what it meant for a new media festival not to use the term “new media” in its name. Second, getting back to the new media term, I wondered to what degree the panelists thought that new media meaning anything affects the authority of the discipline? And where I’m going with this is that when I gave a talk this year at a University where the new media professor was actually a photographer with dreamweaver skills. She told me that she felt, one, grossly unqualified because she was a photographer, and two, that billing herself as tech was simply a way for her to get a job because everybody was looking for that. Also, it was a convenient way for schools to get teachers to do more with less.

Joe: I can answer the first question first, which is I think ”New media” is not in the title partly because we all sort of cringe at the name, and we teach in the new media department, so it was fun to get away from something like that this summer. Honestly, it wasn’t a conscious decision. The other thing I want to say is that the festival itself is showing stuff that’s not art, obviously that’s part of the underlying thing going on that we want the festival to do, and as the festival grows, we keep bringing in digital media, new media,, maybe those people from the radio station- and have that, more of a conversation between the arts and that “new media” that’s not “art new media,” and so “digital media” helps maybe to start having that conversation on a new ground.

Mary: Yea as far as the market forces, like what’s cool and what’s not- these things change with the times. Game design is a really big program, there’s a million game design programs- if you’re an artist if you work with games, are you really going to be happy and fulfilled doing that? A lot of it is how you, as an artist, can be fulfilled sharing what you know in the right context, and that the student expectations are the same, so I think there’s always pressure. And again, these institutional definitions of how these fields get working…it really depends on how much the artist feels comfortable and what they can offer. I can definitely take interesting images, still images, and turn out digital prints, but I would not call myself a photographer. So I think it goes both ways, on some level. And at some point, every discipline is engaged in new media; scientists are doing visualizations, photography is doing digital prints, a lot of artistic disciplines are incorporating [digital programs such as Illustrator]…the digital tool is part of the process, and I think what separates a lot of the work here at the festival is that it’s really engaged in that medium and putting itself in that medium and saying “we’re not necessarily photography, it can’t be done through another form, it needs to be done through this particular set of technologies and particular human interactions.”

Marcin: Another aspect of it is that people who got themselves into teaching in the new media departments or digital departments usually came from one particular field, one particular thing they were doing, and they have to learn everything else. That was pretty much standard practice, that you would get a job and in the beginning teach half painting and half photoshop. You would also have to teach web design, and eventually you would expand your horizons. I think this is the tradition that remains today, you just simply have to deal with whatever is there…and also the softwares keep changing. [You have to] teach five softwares and remain fairly on top of things. We’re meant to be that way. The new media- or digital arts teacher- always has to accommodate to certain circumstances.

Audience member: One of the beautiful and interesting things about digital media is accessibility and the power of distribution. When this is put into the context of art and curatorial practices, I see a conflict. Look at what it took to make the New Museum of Modern Art in terms of money. The fortresses protecting precious objects are still the dominant brand associated with art. How do you see digital media working in relation to these fortresses?

One thing that got me thinking about this is I went to a fabulous photo gallery in California, and when I mentioned digital photography, the woman behind the desk said “No pixologists here.”

Christiane: I think one of the great assets of new media art, and again it doesn’t necessarily apply to photography is that is can circumvent these structures when it comes to net art or a lot of art that is happening on the streets or in the festivals- it has a bigger audience than it ever had, it reaches more people, and it has an effect on life; that’s what art always wants, I think. In that case, the question is, do we really need the approval of the fortress to make a judgement here, or isn’t it more important that it gets to people, that there is an audience, that artists’ work still get commissioned? A lot of the art is also not appropriate for being in the fortress, or its incredibly difficult to bring it there if the museum is just alone in a network, and it’s a highly participatory piece. There are so many obstacles to audience reception within the museum. You’re dealing with a different audience, and you’re dealing with a radically different understanding.

I don’t think the museum fulfills any roles as a measurement of quality, of approval, or anything, I think the important role is to assess what artistic practice is. If new media is developing on its own, outside of the museum, we’re really writing two artist histories: one that’s happening in a subculture, or a different kind of culture, and the traditional art that’s always going to be painting, et cetera- and that would be a tragedy. I would like those to be seen together, I would like new media to be in the art history books as art with a capitol A, as anything else. But, for distribution and access, I think we really don’t need institutions anymore, and they’ve lost their position to some extent, in regards to that.

(Same audience member): Wouldn’t you agree that for artists to be validated they still need to go through the old system? Even people like Shepard Fairy and Banksy, their validity comes from the old school. And when I say validity, that is their ability to garner financial compensation for their creative efforts.

Christiane: The art market is very important here, and many new media artworks cannot easily be sold. That’s a separate issue. There are, however, artists whom I would mention to my colleagues at the Whitney, and nobody would ever have heard their name. But at the same time, they’re getting MacArthur Genius Grants, high level commissions constantly, and they can make a living off of their art, while the traditional art world has no clue who they are. So I think the support is possible outside of the traditional art market, but it’s only a small percentage of artists who manage to do that. It’s also that in the medium itself, how much do you want to make the medium conform to something that is sellable?

Magda: But at the same time, there is this scramble in the institutions to accommodate those doing different processes, so there are curators in many major institutions like Christiane, who struggle with somehow understanding putting those new media in the same place, and yes, it is a validation because I think most new media artists would be very happy to be called artists, with out the [qualifier] that describes their form. So the institutions in a certain way attempt to help this history accommodate things that escape.

Marcin: I wanted to add something the distribution of digital art in the context of the museums. I think there is also a huge amount of resistance there when it comes to formats that can be sold. In 2007, I was was trying to facilitate a piece by jodi, who are the classic hacker artists who work with games, now working a lot with the internet. The piece that most thought about purchasing required internet functionality, it was basically based on the internet for the piece to be properly displayed, and they requested that the piece have constant internet access; and because of that fact the sale didn’t happen because of the regulations the museum had at the time. So you see that there’s some kind of legal block there, still even now the system is not ready to be purchasing that stuff.

(other) Audience member: As a curator, I find myself more and more wanting to emphasize digitally-based media, and I’ve been doing more and more shows. I sort of have the opposite problem, which is out of all the students coming out of school, and there are a huge number of MFA students coming out – very few of them are working with digital tools, particularly coding, as just another arrow of the quiver. And so it’s interesting to do a show specifically to try to find playable computer games, original computer games;I found that very difficult to find them, and I ended up more emphasizing the game world and finding things that could be interpreted as contemporary art there. And so I’m curious, why…are so few students emphasizing that, and what could we do to make more students just assume they would learn how to code, as well as push around pigment on canvas?

Mary: The question of coding goes into this larger history. I teach at Dartmouth down the road, and in the sixties the basic computer language was taught there, and it was basically to have everybody learn how to program. There was a big ethos on campus, everybody must program. Many of us in the room may have learned BASIC as our first programming language, and so there’s this interesting question, “oh, that did work?” There was a literacy, it was this exciting thing, and things were made by the program using that programming language. But it fell by the wayside because it does take a lot of time, and it is really difficult, and I’m still very surprised after everything, through this kind of revival, that there are very few institutions that have core program in literacy, and the base of an undergraduate education outside the arts or in the arts. So I think your question raises this larger cultural thing about literacy, who’s getting to author or consume, so there’s this greater cultural question of who can be an author, who can consume, who can produce or disrupt. You see that in our technology, how they become more appliance like and less hackable, and artists keep fighting that and keep jumping into that system

I do think there are a lot of venues for student work. The game art thing is particularly interesting because many students doing game art also really wanna do professional games, so there’s this tension between [gaming and art]. I don’t know if you know the festival Indiecade- and there are some really great venues where game art has seeped into quite large areas of consumption, so I could just hope it’s happening. But from my perspective it’s really increasing from going to the gaming conferences.

Marcin: I also wanted to mention that coding is sort of a disappearing art as far as anybody doing anything right now, because there’s a culture of mass media production that is geared toward ready-made solutions. All these softwares are customizable…

Audience member: I would dispute that. You were at the same conference, and I think you were sitting there when one of the specialists in the game industry said that she won’t even look at a graduating student who’s not an expert with code.

Christiane: I would think it is highly dependent on the academic programs and how deeply the students coming out of them got engaged with the medium. I think Casey Reas and Ben Fry have done a lot for media literacy with Processing. I don’t want to make it sound as if Processing has been the only effort in increasing programming literacy, though. Whenever I refer to Processing’s success on panels in Europe, people immediately jump on me saying, “Why don’t you mention all the other open source programming environments that have been developed here?” So I think it’s definitely there, you have to be in a program that supports it, and in many schools, it is more superficial; you’re learning softwares, you’re geared toward industry production, and there are others that really deeply believe in programming.

Audience member: To add to what Mary was saying… I just wanted to mention aesthetics, because it is quite different than painting and quite different from physical space. Photoshop is just so integrated into many students’ lives that they just don’t even think twice before they put things together in that way.

Tamas: I actually find it pretty disturbing, that’s why I think that art departments should go back to pure digital coding, because Photoshop is really the aesthetic, there is a certain aesthetic that is encoded in it, so you basically just do whatever Photoshop can do

Christiane: I think there are so many aethetics at play; you say the aethetics of digital is different from that of painting. Well, there are digital prints, for example, that come very close to the aesthetics of painting. When it comes to data visualization that constructs its environment real time, on-the-fly from-life data, completely different aethetics, and for me that’s one of the many distinctions; is technology a tool, or is it a medium? I’m not saying one is better than the other, but the aethetics are radically different. So I think part of the digital may be rooted in quite traditional aethetics, and other parts of new media are far, far away from it.

Audience member: I terms of the technical part, I really don't give a damn about the technical part, because I want to get to my personal statement as quickly as I can. And I didn't come to working with a computer until about five years ago. Now I have my prints printed by a master printer. So as important as the technical part is, a chisel is a chisel, and if you know how to make one maybe that does something for you personally, but I don't want to know how a computer works, I want to be able to use it as a tool.

Christiane: I think that goes back to one of the first questions that was asked. I think that's completely legitimate. I think that for some artists, the technology is a tool they don't want to be deeply involved with, for others it's essential to have that literacy and to build it from the core. And I think that's all perfectly legitimate, but what complicates matters is that it all arrives at very different outputs and very different aesthetics and its all lumped together under one term and that's really problematic and that's why we need to discuss it again and again.

Audience member: Most of the time I would agree that digital media has built into it inherently collaborative potential. Could anybody on the panel [give some examples] of how this potential collaboration could be used for the good of humanity in some way?

Mary: I’m thinking of the Feral Trade Project, and not necessarily technology-related projects, but there are sort of subversive trade projects that are led by artists all around the country, so alternate networks, alternate economies. There are some art networks who have been able to take that on. Specifically, some of the projects we’ll see today reflecting on sustainably and environmental issues- I think there’s a lot of that because we can use our technology to connect with other people and connect with place. Like this festival's trying to do. There’s also the whole idea of fundraising efforts and games, like Free Rice, which is a set of games that when people play them they donate free rice to other countries. There’s a lot of social change in gaming that happens- even the Kickstarter campaign, where you can start a fundraising effort for grassroots projects, where art is enabled by technology. So I think your question is really big, there are a lot of places that any of these tools could be used for social change, and there are a lot of places where artists can reflect upon social issues, and there are even more ways than artists can use connections. And I think one of the hallmarks of network art in the 90s and even now in contemporary work is how people connect. So interrogating why and how people connect and playing with those rules and looking at the power structures of those systems of connection- from power structures from Josh On’s theyrule, which looks at a political and social power among people, to other kinds of projects that are depoliticized and about exchange value. So I think it’s a really good range of things, and some of the projects here will address that.

Joe: I was thinking Christopher Robbins from Ghana Think Tank, who’s speaking here.

Audience member: Are there examples of where it’s been effective? That it’s helped with the education in a third world country or where it’s helped with redistribution of wealth?

Mary: Yes. I think we can find successful projects for you, and it’s gonna take a little bit of looking at what you mean by success…for example, I also run this research lab, so it’s kind of an artistically-infused social activist research projects, so they have a clientsʼ idea of the world. and I think that it just really depends what your goal is. If I can make a game, can I prove that it’s shifted every one’s attitudes in culture through a longitudinal study that’s harder. But can I show smaller changes and small evidence of shifts, it's easier to study. So there’s lots of studies done, sociological studies about empathy, and there are good resources that are printed about this so I could just point you to some of those.

Christiane: And just to mention some complete examples- a lot of it, I think, happens on a micro level within a community…Natalie Jeremijenko, for example, took her modified [robot] dogs to a school in the Bronx, and they discovered that one of the fields there was highly toxic, a lot of radio exposure- it's embarrassing for the councilmen, the city actually had to react to that and do something about it.

Esther Polak's “Milk,” which she started in Latvia and then took to other countries like Africa, really engages with the milk distribution networks in Africa of herdsmen versus dried milk products.

System 77's project, which built a fake operation, had its tent in Vienna in the city and claimed to basically sell military drones to private citizens. It created a huge, huge response, up to the level of the EU because it is something that is up to the government, basically, and private corporations engaging in that business would be a huge risk, and that's precisely what the artist wanted to do and the discussion they wanted to start. So I think a lot of these projects have impact, sometimes on a very small level within a small community.

{ 2 comments }

Marcin: “I’d also like to mention that naming the discipline of art by the medium

is kind of a modernist thing. It wasn’t always like that. It isn’t like

surrealism or expressionism; there’s video art, there’s film art,

there’s all these new technologies, but we threw them into this one bag

and called them “new media,†and that’s really a modernist thing. It

would make sense for it to end.”

Yay Marcin! That is a really helpful analysis.

This is a good discussion. Thanks for the transcript.

Yes, thank you for posting this.

Comments on this entry are closed.