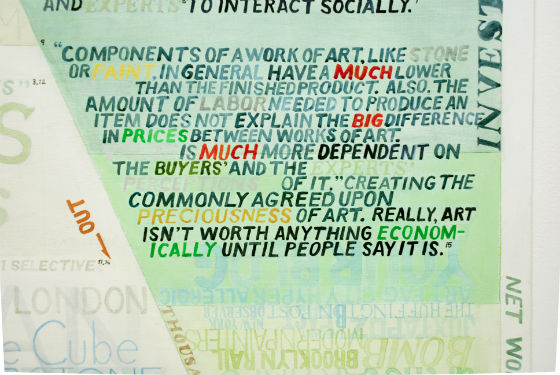

William Powhida, Oligopoly (Revised) (detail), 2011, Graphite acrylic ink, colored pencil and watercolor on panel, 60 x 44 inches

WB: But you're seeing these artists who are bitching about the art world. You have to have seen that and thought, “Hold on, they're missing this,” or “They're not doing it quite right,” or “I have something to add to that.” What did you think was missing?

WP: What was missing was specificity. Even with Guy's work, he was like, “Hey, I'm big sweaty painter guy. I make paintings so big I have to paint them on the roof.” It was kind of a thinly veiled Schnabel thing. Then he's like, you might also know Catholic Hangup guy or whomever. He could only critique in generalizations. I don't know if it was because you weren't actually supposed to say peoples' names at the time, or it didn't occur to him, or it was too risky. But it's hard to make arguments or have a rational debate about something if you can't have specific examples. If you're making an argument and you can only say “the galleries” or “painters” or “this kind of artist,” and you don't have anything specific to use in articulating what you're talking about, it makes it a lot more difficult. Invoking somebody's name seemed to be more powerful in a way, made people pay more attention or look at it.

WB: Well, it certainly provokes a reaction. I remember Jerry Saltz loving your Art Basel Miami Beach Hooverville piece, because you put him in it. And also because he wasn't actually there.

WP: For me, one of the pieces that somebody had a reaction to that wasn't, “Ah, I'd like to own it or laugh at it or be self reflexive about it” was when I did this hex drawing on Zach Feuer. I was putting my thoughts in his head, like, “I'm not going to show these big horrible paintings.” But he didn't take the Jerry Saltz route of thinking it was funny. He was deeply offended, upset, and hurt, and [Schroeder Romero, who showed the work] wasn't asked to come back to NADA, even though they were founding members. It was a specific kind of critique to Zach, with the idea of this second, third, fourth, fifth coming of bad, bad painting, which has been a spectacular triumph for other people.

His reaction to it was fucking amazing in a way, because everyone else who didn't like [Feuer], or didn't like the work, or the gallerists who said, “How did he win the fucking lotto,” they all had a totally different reaction. It seemed actually risky. It seemed actually to have something at stake. I realized if you put in things that other people can recognize, it creates this common ground and makes the work more social, adds this element of realness to it that other people can latch onto. It's not just a generality where you're projecting whatever you want onto them.

WB: I feel like there are some similar things going on in criticism. If you're doing your job, you're very often calling someone out, taking the broad generalities of history and press and saying, where that's in operation.

Also, though, I think about the choice of targets – plenty of times, you see a terrible show, but you can't say anything because it's not big enough or successful enough to merit a take-down. You're always fighting between two sets of morals in criticism, and it hurts. Did having to think about those issues as a critic spill over at all, or do you see that as a separate thing entirely?

WP: With the first pieces, most of the artists I was criticizing had already succeeded — they were selling work for lots of money, and the press was paying attention, like when Dana Schutz had that Vogue spread. There's this myth created around the artist, a perception of the artist being successful, which becomes so much talk. I was trying to deflate some of that through the work, and very specifically the painting magazine spreads.

Early on, I didn't really give a fuck that it might hurt Dana's feelings – and I don't know if it did, and I don't really care. But the contention was also that this particular kind of painting has been done very similarly before. It's not a knock on her skills or even on the genre.

It's just that the market came back with such a fury in 2004, 2005, 2006, and then slowly shit started to fall apart, until we found ourselves in our current state, which has evened out but is still pretty fucking disgusting. But this is not that kind of boom time, and it's put the power of deciding what art was back in the consumer's hands. So all of a sudden, it was about individual tastes and connoisseurship again, and I'm really interested in how that affects how we decide what good art is, what excellence is.

WB: So there was the sudden appearance of what the public would call “good art” when the market picked up –

WP: Yeah, to me, it wasn't good art. It was stuff that didn't make any sense to me coming out of graduate school. It was just so conventional.

Yeah, I'm targeting successful artists, because they're the standard bearers of what the market is saying and what, by default, the 1% of the art world is saying, is successful art. I mean, when you step outside of that and look at what's going on with nonprofits or places outside New York City, you see there are other artists doing things, but we don't tend to hear about them in the same way. And a lot of those places are still funded the same way – the pool of money tends to come from the same place. And then once you start to deal with institutions, anything you do has to go through the marketing department and be approved by the director and make sure it fits with their mission. It's like, when the fuck did my art align with that? I need your approval?

WB: Even major museums will get their works together and then go back to their philanthropist base and ask them for money to ship everything in.

WP: Actually, a young artist I know, who does not have gallery representation, was approached by the Whitney and asked to submit her work. So she did, but didn't hear anything. So she called the curator back, and the curator said, “Oh, I'm really sorry, I didn't realize when I asked you to submit that you didn't have a gallery, because we rely on the galleries to fund these projects.” My friend said, “You're telling me that I have to have a gallery if I want to be part of this program?” and she's like, “Yeah, that's how it's works.” And this particular artist did not want to have a gallery.

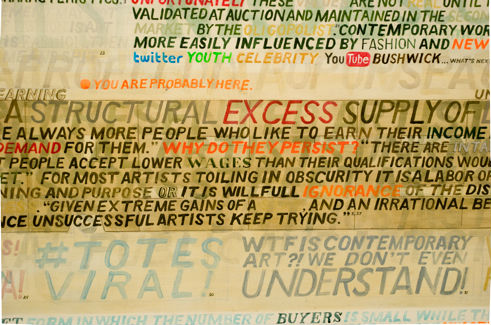

William Powhida, Oligopoly (Revised) (detail), 2011, Graphite acrylic ink, colored pencil and watercolor on panel, 60 x 44 inches

WB: So, you're a downer, all of this stuff is a downer. Do you have any ideas for how we fix any of this?

WP:You know, not that there's a solution proposed in here, but it's the idea that everyone's just fucking yelling about a particular belief. The economic overlaps with the social, with the religious. I spent this inordinate amount of time having this conversation on Twitter with this woman, a “Tea Party Patriot fiscal conservative who differs with the GOP on social issues, a deist with strong belief in God”. Her post said, “Occupy Wall St., its these leftist teachings in public schools and colleges and the left-leaning media. We must fix this.” She was calling everyone an idiot, and I was just trying to have a civil conversation with her, to see if it was possible. In her one sentence description, you have not only have to contend with the fact that she's a conservative and differs with the GOP on social issues, but that she's also a deist. Those are three major things that are going to make having a rational discussion a problem. And I'm not even arguing, I'm just listening. So I think one of the solutions is that people have to listen, get over themselves and potentially compromise. Looking at this over the past six or seven months, it's really tempered my own approach to yelling at people on Twitter, because it's futile.It also comes out of my own experience making work: it'll either be interpolated by the art world and sucked up into the apparatus, or the market just doesn't give a shit, because we can't impose things on people. I think there's this general idea that if we just fucking yell enough, we'll have this revolution – that somehow we're magically going to convince this entire sphere of people that they are wrong, have been wrong the entire time, and should get onboard on the left train, which is at historically low levels in this country. Center is left, right is center, and anything that looks like socialism is now fringe. We don't really have a left. The art world purports to be really left — at least grass-fed cow left — but it's really not. It's completely dependent on the funding that comes from the right.

So there's just a general hypocrisy, and I'm not going to lecture anybody on hypocrisy, but it seems to be the natural state of affairs for everybody, right and left. But this woman's screaming, “These people are idiots! Mr. President, you lie!” and I'm like, we're all really that angry? Where's your sense of humor?

WB: It doesn't seem to fit: let's have more ambiguity and compromise and coming together, but also these specific people are assholes. So is this purely a political thing you had to get off your chest? How do you see that fitting in? Maybe it doesn't need to, I'm just anticipating that reaction.

WP: I don't see them as being linked, like if you understand this, you'll understand that. But even if you could understand what caused the financial crisis exactly, you knew everything and had God-like perspective on it, there would still be people saying, “You're wrong. We need to free the market. I'm going with Ayn Rand. I can find some way to spin it and show it's not Greenspan's fault, it's not Goldman Sachs. If we'd just free the market”¦”

I don't know what to do when that happens.

You have all this talk, and you have 1% with about 35% of the wealth, which is where is the money to fund the government is coming from, in terms of political campaigns and lobbyists. I'm trying to make that connection.

It's not even that these people are assholes, it's just the way things are structured. Let's say Agnes Gund is on the board at the Whitney and they go for a preview of the shows coming up that season, before the public knows about them, and she knows they're going to be showing Ryan Trecartin and two emerging artists that most people don't know about. Those trustees can walk out the door, call the gallery and say, “Buy me seven Trecartins,” before anybody knows about it. In terms of sustaining prices, you're hanging out with the artists at galas, with other trustees, in the area where collusion need not be formal — it's simply sharing information and talking.

Hopefully, this one isn't saying, “Agnes Gund is a bitch.” I don't know Agnes Gund, I don't even know what she does anymore, but she's one of the top 200 collectors. These things keep coming up in the work. You don't have to get personal with it if you're just looking at the system. My friend keeps talking about the idea that politics shouldn't be personal ever, and I say, “Well, people run politics, so how do you talk about politics without talking about the people?” But politics itself should not be personal. I'm trying to move away from that a little bit.

{ 4 comments }

Can you make a single-page version of this? Thanks!

this is incomprehensible, and unlikely to have any practical effect — just like most contemporary art!

Dude you write about art all day and this is the best you got?

More substantially:Â

Of course Powhida’s show is “unlikely to have any practical effect”. Everyone from Picabia to Oscar Wilde has called art useless, and most of them have recognized that this is not a definitive fault. There exist reams of text on the topic of why contemporary art is so useless, if you’re interested, though I get that understanding might lack the self-satisfaction of contempt. In any case, I can recommend a number of good design blogs if that’s what you’re looking for.Â

Besides which, Powhida spends a large part of the interview you’re commenting on saying explicitly that his art is unlikely to have any practical effect. He says that he “doesn’t know what to do”, that “it’s futile”, that “it’ll either be interpolated by the art world and sucked up into the apparatus, or the market just [won’t] give a shit”, that “Even if you could identify and articulate the problem exactly, there are still people who would just disagree fundamentally because it doesn’t line up with their ideological position.” He repeatedly mentions the circularity of the arguments he’s entering into, and the slim chances of changing that. Even if you were to read nothing more than the image at the very beginning of the interview, you would have noticed it’s titled A Continuum of Ideological Futility.Â

I agree that most of Powhida’s subject matter is, in some sense, “incomprehensible”. I think he got that across when he said he “doesn’t really know how it works”, and when he stated that his goal was “to represent th[at] complexity.” That said, I feel like your comprehension problems might run deeper than that.Is there any particular point in the interview I can clarify? I have seven thousand-odd cut words sitting around in a Google doc, so I can almost certainly shed some light on anything that was left unclear, if you have a specific question.

Comments on this entry are closed.