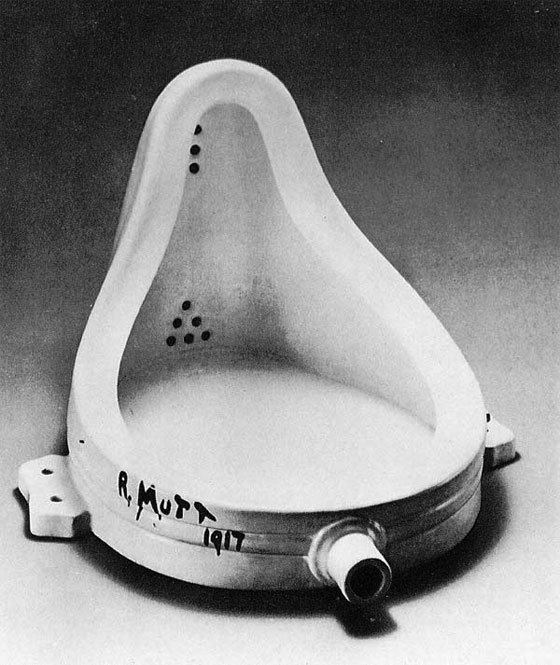

Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, 1917

In an interview at the St. Petersburg Times, film director and screenwriter Andrei Konchalovsky tells audiences that the state of criticism is less than shining. Too many critics share the same opinions, bright names are vanishing, and independent voices are rare. I feel his pain. Web publishing in particular often rewards reactionary criticism and fluffy reporting. And yet these aren’t the problems that Konchalovsky discusses.

Instead, he anchors his criticisms on a survey taken by 200 critics. When asked which work of art contemporary art they liked best, many cited Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain” [A urinal]. “I believe that half of these critics inwardly, secretly don't agree that the most outstanding product of the 20th century is a urinal!” Konchalovsky says, “I consider it a shame to give in to the conformist herd instinct, a dictatorship of political correctness, a fear of going against the grain and looking unmodern.”

I’m not sure where this study comes from, but when talking about why art criticism is in the shitter, I’m not sure I would start with a urinal. “Fountain” isn’t my favorite work either, but few would argue its success in swinging art’s focus from physical craft to intellectual interpretation. That was a big deal. It’s not unreasonable that so many critics would put Duchamp’s sculpture at the top of their list.

As per what the results of the survey say about the state of art criticism, I’m not convinced that our interest in Duchamp should be evidence of that failure. Sure, people misread Duchamp and the Fountain all the time. Critics often make the mistake of repeating Duchamp’s quote about seeking “total anesthesia” by chosing an aesthetically neutral object. No one seems to have looked at the objects long enough to establish whether that’s true. Even a cursory look at the urinal, which has been rotated 90 degrees, or at his unmodified “Bottle Rack,” reveals either sculpture to be beautiful, strangely compelling – anything but aesthetically neutral.

Given that it was The Philadelphia Museum who quoted the artist unquestioningly on a wall label, I’m not entirely surprised Konchalovsky is drawing such harsh conclusions. However, two bloggers did not make these same mistakes.

Recently, Blake Gopnik claimed that the Duchamp urinals we now see in our museums were “visibly handcrafted replacements for his mass-produced industrial original, which disappeared early on.” That such an error could be made in a broadsheet publication is an embarrassment. Blogger Greg.org called it out and corrected it, citing the Economist. “Duchamp’s Fountains replicas include two or three actual, vintage urinals Duchamp signed, showed, or sold;” he writes, “and somewhat more than twelve which were cast, just as porcelain is, from a clay sculpture [aka ‘the prototype’] made from Arthur Stieglitz’s photo of the ‘original.'” That the original urinal may never have existed at all (a point made by an AFC commenter and supported by art historian R. Shearer) is simply gravy.

Regardless of how convinced you are by Greg.org or AFC’s commenter, it’s hard to deny that there’s some good criticism going on here. It’s also worth mentioning that this is happening on two independent publications. While I obviously have a rather large stake in this, to my mind it demonstrates both their vitality and need for support.

{ 3 comments }

It’s obvious that the position of any particular art object in a canon should be called into question on its merits. This is equally true of the Mona Lisa (which is a pretty middling portrait of an ugly lady) and The Fountain. The problem with Andrei Konchalovsky’s meta-criticism is that it addresses the issue from a reactionary viewpoint, rather than one that is actually critical from a contemporary perspective. His answers to the interviewer point to his prejudice, one shared by many people with a low opinion of contemporary forms of art, that anyone with “common sense” could not possibly consider “a urinal” the most important work of art of the 20th century. Regardless of what one thinks of Duchamp in an aesthetic or critical sense, it would be impossible to deny the far reaching and paradigm changing influence of Duchamp, his practice, and particularly his ready mades on the progress of all of the art that would take place later. Indeed much of the art being made by practitioners today bears far more resemblance to Duchamp than it does to artists that came later in the tradition of modernism. To react against Duchamp’s place in the canon isn’t really to react against the influence of his work; that much is settled fact. Rather it is to react against the legitimacy of modernism, and the post-modern phase of modernism in particular. The vast majority of people in the world still reject the validity of even non-representative art made in traditional media, let alone works like The Fountain that are not only non-pictorial, but appear to reject even materials from which art objects are traditionally made (even this isn’t really true of the Fountain, for as pointed out above most or perhaps all of its iterations are artist-made porcelain casts, a well established artistic medium). The rejection of modern and contemporary modes of working in art privileges older forms where the virtuosity of a practitioner could be more readily determined in an “objective” manner (when the criteria of a good painting is looking like the object it depicts it’s fairly easy to say what’s “good” and “bad”), and a romantic vision of a kind of artist that never really existed. He belongs in the ranks of commenters that decry the assembly line production model of an artist like, for instance, Jeff Koons; while completely idolizing Old Masters who are known to have had less hand in many of “their” works than even Koons does. This lazy kind of criticism attacks contemporary and modern art for its supposed pretensions and arbitrariness while leaving the pretensions and arbitrariness of making depictive art after the invention of photography unexamined. It also, as noted in your writing above, treats Duchamp and other artists working in post modern paradigms simplisticly, denying them the complex context and theory they were and are operating in. To imply that The Fountain is “just a urinal” is on the same plane as saying that Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is “just a picture of some prostitutes”. The problem with contemporary criticism isn’t too much conformity or beholdenness to the canon of contemporary art, its a lack of rigor in education and research in contemporary art itself.

That Konchalovsky’s point of view may or not be reactionary is somewhat besides the point because a number of his observations—particularly his suggestions that critics exhibit a herd mentality, and that a reflexive fear of seeming out of it lies behind some of the worship of Fountain—are not wrong. I’ve always admired the piece, and Duchamp’s oeuvre as a whole, but I’ve never overlooked the smugness and cynicism that underscored much of his thinking about art—an attitude which, in our own time, has metastasized to become a core cultural value. I’m personally of the opinion that if, as a society, we were to direct ourselves away from the structural imbalances that currently bedevil us, Fountain’s relevance would likely decline; if not, it will be on critics’ top ten list well into the 22nd century.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bBc8Oh4kA2U

Comments on this entry are closed.