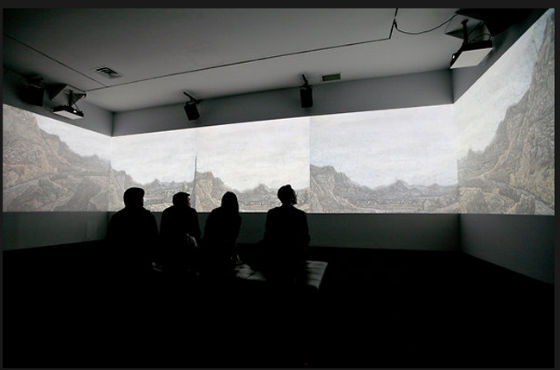

Werner Herzog's 'Hearsay of the Soul', installation view

Hyperallergic's Peter Dobey has decided the entire Biennial is held together by a single work of art, Werner Herzog's Hearsay of the Soul. To prove this thesis, he blows up a quote from some wall text, applies it to a myriad of art cliches, and expects that this will all somehow support the idea that the Biennial is about different states of mind. I'm not convinced.

For those who haven't yet seen the show, a bit of background: Herzog's piece is a five-channel installation that combines slow pans over the landscape etchings of Dutch artist Hercules Segers (1589) with the music of Dutch cellist and composer Ernst Reiseger. The performers—Reiseger and a pianist—look as though they are in a trance.

Dobey and I both agree this makes for a schlocky piece. Dobey goes so far as to call it an “exemplary iMovie experiment”, I said it didn't need all those “bells and whistles”. We also agreed—with each other, but also with Herzog—that the piece is mostly an homage to Segers. What we don't agree on is its importance within the show.

“The context of Hearsay of the Soul within this year's Biennial, and what relationship Herzog's method of appropriation has to the show's undertaking, is indicated by the words of the director himself,” Dobey tells us gravely, before quoting Herzog on Seger: “His landscapes are not landscapes at all; they are states of mind; full of angst, desolation, solitude, a state of dreamlike vision.” From this alone, Dobey draws the conclusion that the piece is the binding element of the show.

Now, I can see how this conclusion might have been drawn. Herzog lists a lot of states, and a disjointed dream may accurately describe the initial viewing experience of any large exhibition. On the other hand, that broadly covers a lot of art concepts and experiences, and Dobey hasn't convinced me that it's particularly true of this year's Biennial. Trouble is, Dobey doesn't actually identify any other works in the show to support his thesis, even though he announces that he's setting off on “an investigation of the conditions surrounding [Hearsay of the Soul].”

After all, one doesn't have to look very far to see that Herzog's reclamation of Seger is a theme repeated throughout the second floor. Immediately outside Hearsay of the Soul are Richard Hawkins' reinterpretations of the butoh-fu notebooks of Tatsumi Hijikata (1928-1986), works that seek to reintroduce Hijikata's collages as erotic transgressions, rather than artifacts of WWII trauma. Around the corner is Robert Gober's curated gallery of Forrest Bess paintings, that sheds light again on an under-recognized artist. Just across the room, Joanna Malinowska displays a horse painting by imprisoned American Indian Movement activist Leonard Peltier to question her inclusion in the Biennial in the absence of Native American art.

These artists easily demonstrate that the themes of the Biennial are more developed than the list of emotional states Herzog listed off. Were there enough of them, they might also call into question Dobey's thought that “at the core of the working principles of this year's Biennial is the idea that we should relinquish the line between the art-making process and the object of art in and of itself.” None of these artists are doing that much to blur those lines.

Truth be told, there is enough performance on the other floors of the Biennial that there's probably a case to be made for this kind of blurring; Dobey, though, never makes it. Instead, he uses “Hearsay of the Soul” as the sole support for this argument, telling us that it gives us “a glimpse into Herzog's thought process”. Sounds good, but there's absolutely no evidence to support that idea. We never hear the director interview his subjects, the camera work is all mechanical rather than handheld, and he didn't compose the music. The fact of the matter is, Herzog gives us extraordinarily little of his own.

And that's a disappointment. Herzog is a great filmmaker, known for his ability to improvise large portions of his scripts, and motivate his colleagues. The touch of his hand is precisely why so many have been moved by his films. None of that was on view at the Whitney.

{ 7 comments }

I agree with you Paddy. Here was my take:

One work getting universal acclaim is Werner Herzog’s Hearsay of the Soul, a five-screen digital projection of the landscape etchings of the relatively unknown 17th-century Dutch artist Hercules Segers. It is set to exquisitely beautiful music: a haunting hymn sung in the Wolof language of Sub-Saharan Africa; a Handel aria; and music by the Dutch cellist and composer Ernst Reijseger. Critics report they were moved to tears. I, on the other hand, felt manipulated. With that music, ANYTHING would be moving, and almost anything else besides five close-ups of landscape etchings would be deeper and more interesting. Why do we accept this kind of heavy-handed schmaltz on film or video but not with the other visual arts? Take a look of this clip of Ernst Reijseger chewing the scenery (overacting) to see what I mean.Â

http://leftbankartblog.blogspot.com/2012/03/2012-whitney-biennial.html

If Herzog created an environment where ANYTHING would be moving, doesn’t that mean he’s an extremely adept artist? Personally, I thought it was a solid work.Â

But Herzog didn’t really create an environment where ANYTHING was moving; the music did that. Making a great work is about more than music selection. I don’t think it’s a compliment when the main thing you say about a movie is that the soundtrack is great; the same applies to an artwork.

Something can be moving but also cheap, easy, manipulative schmaltz.

Can you write more about stuff you actually DO like? Most of the articles on this site always seem negative, or stating how others got it all wrong or came up short.

Dear Tim, “THEY” already shut down http://cathedralofshit.wordpress.com/

Let others to have a bit of healthy reading rather then being owned by artsy people with massive funding and political interests 🙂

Schmaltz is annoying and uncomfortable, but it may be that a new romanticism is trying to come out in contemporary narrative. For those that responded to this installation, I think it touched on a sense of loss and longing. Very European, very ‘saudade’ perhaps – to feel a mixture of loss, fatality, hope, nostalgia. And the video is ephemeral, time-based, just like the programmed performances upstairs.

So I think the merit of the work is that it points to what is no longer available – a landscape that has not been mapped by Google Earth, a membrane between public and private, a question about the future of museums as caretakers of cultural objects in a time of performance, entertainment, and social media. Maybe that’s enough.

Comments on this entry are closed.