Lu Zhang: topo(log) typo(log)

Institute of Contemporary Art Baltimore

The George Peabody Library

17 W. Mount Vernon Place

Baltimore, MD 21202

Exhibition Runs:

Nov 12 to Dec 19 2015

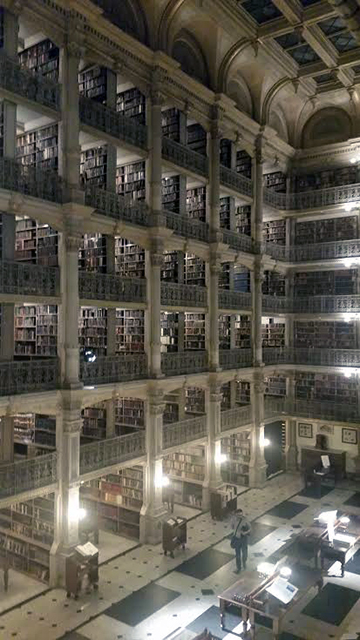

The George Peabody Library, completed in 1878, is widely considered to be one of the most beautiful in the world. Its five stories of cast-iron stacks wrap around a skylit atrium, dripping with mis-matched architectural features from the neoclassical to gothic pendants. Its special collections hold everything from Victorian first editions to anti-Protestant propaganda leaflets dating from the Reformation. One could easily spend a year wandering its curiosities, and that’s exactly what artist Lu Zhang did.

Her project topo(log) typo(log) is the culmination of a year-long studio residency, jointly facilitated between the ICA Baltimore and the library, which cleared off a few shelves of archaic science books to create a studio space for Zhang. During that time, Zhang embarked on a sort of non-objective research project—approaching the fruits of the Victorian impulse to collect and index knowledge with a contemporary gaze trained by scrolling, surfing, swiping, and favoriting. The result is a collection of single-edition printed matter loosely based around the Dewey Decimal system of relative location, each piece corresponding to a different level of the library’s physical structure. Zhang’s work is arranged on the atrium’s study tables for perusal, beginning with a large, cloth-bound book with content sourced from the concept of “General Reference.”

The book is a collection of images, mostly sourced from the 18th Century Diderot’s Encyclopédie, as well as archival architectural drawings of the library itself, and other works from the Peabody collection. Zhang xeroxed images that caught her eye and arranged them as a progression informed by formal or symbolic associations. An illustration of symmetrical balustrades might lead to an image of a neoclassical structure, back to the library itself, and on to other signs of the archival impulse—ending with a seemingly blank page that captures a hairline flaw in the bed of the library’s copier. The piece brings to mind Dina Kelberman’s ongoing artwork “I’m Google“, in which reverse-image search leads the artist and viewer down a rabbit hole of ever-slightly-changing imagery. In both cases, it’s suggested that we have such a surplus of collected knowledge at our fingertips that the most arbitrary or personal forms of sequencing it are just as valid coping mechanism for information overload/processing as any search algorithm.

Here though, Zhang’s work feels precious—the images have been painstakingly xerox-transferred by hand-pressing to archival-quality cotton paper and bound beautifully. Conversely, the act of appropriation and the photocopier process by which they were transferred evoke punk fliers or zines. And Zhang seems to relish in that “not-precious” quality—when we approached the work at the opening, another attendee who happens to be an archivist for another institution blurted out “I can’t believe you aren’t wearing gloves!” Zhang replied that she’s looking forward to the book accumulating scuff marks and smudges, adding “I make objects because I love touching things.” It’s easy to imagine the book bearing a warm patina, marking the passing of time and use as so many others in the library have. The piece, along with the rest of the work in the show, is slated to join the Peabody’s permanent collection.

The next level, “Biography”, is marked by two quarto-sized volumes, again beautifully bound. Each page contains a single chapter heading from Cervantes’s The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, the plot of which is famously set in motion by the burning of Quixote’s treasured library. Don Quixote’s fictional life is thus reduced to a series of bullet points, not unlike a historical timeline. It seems to suggest the minutiae and details of one’s existence are eventually forgotten, survived by only “highlights” or vague summary.

“History” is recorded in a folding pamphlet with details of various library surfaces and their wear juxtaposed with what appears to be a transcript of a guided tour. Marble might show erosion from countless footsteps, while a wooden desk top might bear the marks of errant pen strokes. Zhang’s artifacts of “Language, Literature, and Translation” again recall the library’s texture, rather than text. She created plaster casts of everything from braille signage and ironwork florettes to contemporary fire-suppression systems. All of these tactile surfaces—including the banal ones most likely to be replaced eventually—are tenderly/clinically cradled by foam, preserved for posterity.

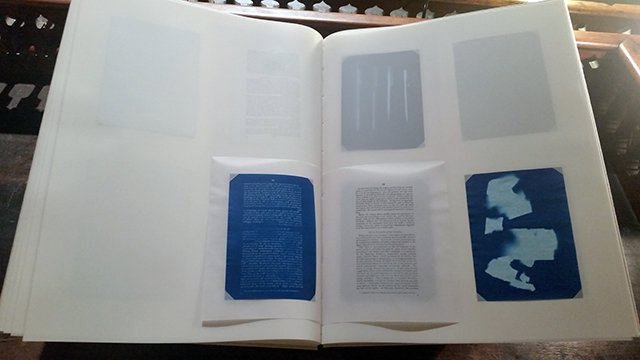

There’s an interesting tension in Lu Zhang’s practice between adherence to a formula, or “rule” she creates for herself and the desire to do something whimsical and illogical. It’s a dichotomy that fits perfectly with the period and intentions of the library itself—so many Victorian creators and archivists of culture aspired to be scientist and artist, anthropologist and poet, adventure-seeker and librarian. The wunderkammer was embraced with conviction as both a collection of personal curiosities and scientific specimens that held some absolute aesthetic truth. And like the Victorians, Zhang seems to relish her role as both archeologist and architect of follys. Zhang’s response to the library’s “Science and Art” level is especially fitting. Sampling text from an old, charmingly authoritative/poetic guidebook to clouds, Zhang bound a vellum folio illustrated with cyanotype “specimens” of imaginary skies. These are created from mundane supplies one might encounter at a study desk—pens, scraps of paper, etc..—exposed to create absurd cloud formations. What’s especially great about these though is their ability to tread that line between fact and fantasy so well. Obviously, these tell us absolutely nothing useful about what a cirrus cloud looks like. But emulsion itself cannot lie—we’re left with a fossil perfectly describing the silhouette of a pen or staple to a curious future researcher.

The top tier of the library, and the final piece in Zhang’s series is “Bibliography and Books about Books.” It’s a roughly 3-foot box, bound in the same cloth as the books, intimidatingly filled with catalog cards. To be honest, I didn’t even begin the undoubtedly exhaustive process of looking through them. If there’s one takeaway from topo(log) typo(log), it’s that the world is full of more things than one could possibly read or see or touch (or remember to put back in the right place) in one lifetime. And certainly not in one year.

Comments on this entry are closed.