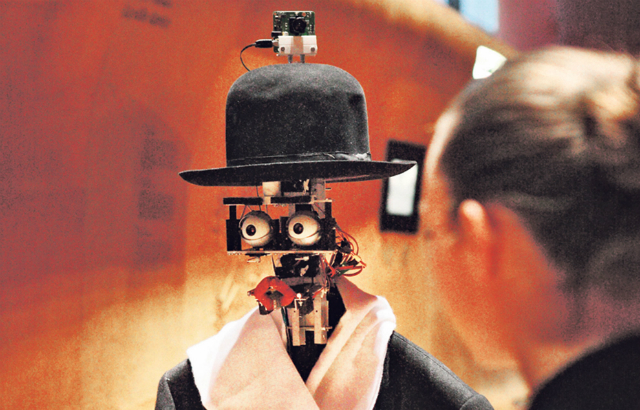

Joe Berenson, the robot art critic. Credit: le JDD

Scientists, we’re told, have invented a robot art critic. Joe Berenson is a four year old robot-cum-research project currently rolling around the galleries of the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris clad in a black bowler and white opera scarf. His robotic exoskeleton supports a camera for an eye; Berenson uses the camera to view hung works, and expresses his opinions with a frown or a smile. He’s the art world equivalent of Short Circuit’s Johnny Five, with a reportedly evolving, algorithmically-determined “artificial taste” thanks to his Rotten Tomatoes-like processing of the responses he observes in other museum visitors.

The brainchild of anthropologist Denis Vidal and robotics engineer Philippe Gaussier, the robot has developed a sense of taste that is “dependent on the tastes of those around him,” says Vidal in an video Yahoo News interview. “The aim is to develop a robot that’s the equivalent of aesthetic exploration of the world and to see if because of that it may adapt itself more easily to the world around.” Joe, then, is a mimic, a so-called robotic mediator of museum publics. He’s also an information gatherer of visitor statistics, a civilian humanoid surveilling attendance rates and profiles, and likely far more effective than a survey.

Of course, it’s worth considering the context in which Joe is operating. The robot is part of the anthropological museum’s Persona: Strangely Human exhibition exploring the liminal boundaries that separate robots from statues, ghosts and zombies, and our cautionary stance on artificial intelligence. “The exhibition invites you first to explore the conditions in which we are led to perceive people, then to discover different devices designed to detect, activate and measure these presences that surround us,” states the exhibition booklet. The non-human, especially dead-eyed zombies or David Byrne’s singing robot, can creep us out. This is an exhibition, then, that is not only about how history has informed how we imagine ourselves, but the techniques we have to quantify what we know about ourselves.

The show, curated by two anthropologists at France’s National Centre for Scientific Research with no prior curatorial experience, is hinged on Japanese robotics expert Masahiro Mori’s seminal “uncanny valley” theory: when a robot looks and acts almost human, the greater the chance of trust and empathy from humans. But when the so-called valley is crossed, that trust disappears – too much realism creates discomfort, and a human is likely to reject the robot. (Coincidentally, we published this essay that discusses how the uncanny valley can be applied to art.)

Probably the most compelling response to the show was expressed by Sciences et Avenir writer Aline Kline, who noted that while we have the ability to attribute intentionality to the figures we animate, it is a bit disturbed how often we imagine their cruelty. At a time when Chicago’s Field Museum has brought back on display its controversial “Races of Mankind” sculptures, we’re seeing institutions re-contextualize previously essentialist, pseudo-scientific exhibition-making that made bold but erroneous biological pronouncements. There’s an aligning between our historical wariness of artificial intelligence with our wariness of difference. So while it appears that Berenson isn’t the robot art critic we originally thought, he does signal our fervor for self-thinking machines that are are unburdened by art history, trends and even our own limitations.

Comments on this entry are closed.