Langdon Graves, Home Circle, 2016, wood, vinyl, acrylic paint and a pearl (all images courtesy the artist and Victori + Mo, New York)

Langdon Graves: Spooky Action At A Distance

Victori + Mo

56 Bogart Street, Brooklyn, NY

Open now until June 26, 2016

Walking the darkened halls of 56 Bogart Street, a pulsating pink glow radiated from the open door of Victori + Mo. I felt like I was in The Shining’s Overlook Hotel and told artist Langdon Graves as much when we met to speak about her current exhibition Spooky Action At A Distance. “Yeah,” Graves responded, “That’s not the first Kubrick reference I got.”

Spooky Action At A Distance is nothing if not creepy. Based on her grandmother’s experiences with ghosts, Graves’ exhibition immerses viewers into a dreamlike but distinctly familiar space of a mid-20th century home covered in flowered wallpaper and a jarring candy-colored palette.

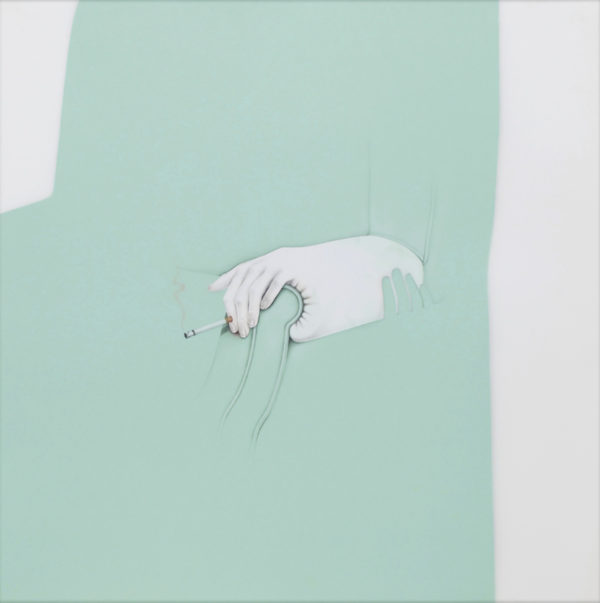

However, all is not what it seems at Spooky Action At A Distance, which is on view until June 26. Drawings of women without faces line the gallery, eyeglasses and hangers merge into walls, and an unidentifiable yellow liquid seems to seep randomly around the space. Graves also repeats imagery throughout the exhibition such as white gloves and cigarettes or pencils passing directly through solid objects, producing an eerie sensation of déjà vu.

Titled after an Einstein quote referencing the unknown in quantum theory, which believers have used as proof of the possibility of spiritual energies, Spooky Action At A Distance not only addresses belief, which is an ongoing theme in Graves’ art, but also the ephemerality of memory. The appearance and disappearance of objects in the show recall the gaps in both our experiential and spatial memories and seem to give her grandmother’s stories a tangible physicality. “I’m struggling to hold onto these memories and there’s this air of preservation to what I’m doing,” says Graves.

Effortlessly referencing the complicated and sometimes impenetrable texts on quantum physics, spiritualism and neurotheology she read in preparation for the show, Graves spoke to me about her translation of her grandmother’s stories into art, the cheery colors she used to represent the undead and ghost stories as a Southern tradition.

Spooky Action At A Distance uses your grandmother’s ghost stories to investigate memory, the supernatural and belief. What initially inspired you to delve into your grandmother’s stories?

About a year and a half ago, my grandmother had a heart attack. We thought we’d lose her. She had a near-death or out-of-body experience. She lost a ton of her short-term memory. I had this scary thought like, “Oh my gosh! What if she’s gone and I can’t hear her stories anymore.” Growing up, she and I would share all of these stories that happened to her when she was younger. I was the one family member who would gather around her and eat it up. I heard these stories over and over, but they were fresh every time. I was afraid I was going to lose my memory of these stories too. After many years, it’s like a game of telephone when every time you remember a memory; you’re remembering it a little bit differently. I’m remembering my memory of her memory. I wanted to get back to the source as much as I could. I started tapping her for these stories again and they were really hard for her to remember. My mom and my aunt started to fill in the gaps. That was an even broader game of telephone: “I remember a white glove!” “No, I remember a purple glove!” I was like, “Nobody remembers this the way it actually is.” Over the last year, my grandmother’s memory is starting to come back a little and she’ll call me, saying “I remembered another detail.” So we’ve had this beautiful reason to connect on a very special level again.

Like anything I start to make work about, I dive into research really hard. If something has a more spiritual flavor to it, I always try to go to the scientific community to see how people are responding to this from a logical, materialist perspective. I got really into parapsychology, neurotheology and Oliver Sacks’ books.

Installation view of Langdon Graves, Spooky Action at a Distance, 2016

I’m glad you mentioned scientific research since your exhibition title refers to a quote by Albert Einstein on quantum entanglement, which many use as an explanation for a soul. Why did you choose to title the show Spooky Action At A Distance and how do you see it engaging with the exhibition?

The title has so many different layers and I fought it for so long because it comes across as a little clunky at first when you don’t know what it references. Also, Trudy Benson, who is an artist I know, had the same title for her exhibition, which opened the exact same week. Talk about spooky…

I came across this book that I immediately knew I had to read called Mental Radio by Upton Sinclair who we normally know for being this socially conscious, corporate ball-busting whistleblower. Turns out that his wife was telepathic and he wrote a book about her telepathy. The book is a series of illustrations that he would do in one place, give her the idea telepathically and she would make an illustration somewhere else. Then they would compare them. I bought this cool old copy of the book and discovered Einstein wrote the forward. The forward basically says: “Without a doubt, these people are amazing minds and I trust them fully. I don’t believe in this stuff, but I believe in them.” That is exactly my position on all of this. I am a believer of believers. It almost doesn’t matter if I believe in this stuff. You need that passionate belief to be human so I live vicariously through other people’s belief.

I began to research Sinclair and Einstein’s relationship and I came across the quote “spooky action at a distance.” I was like, “Einstein said that? What’s he talking about?” I began learning a little–as much as you can through the Internet and books–about quantum theory. Basically if a subatomic microscopic particle of something is removed from its other particles, you can observe one and make predictions about the other. A lot of people who are true believers see quantum entanglement as the potential for energies to be dislocated from the body.

In this show, there’s a lot of splitting or separation of parts where there’s a blockage in between. I’m setting up two removed parts where you can predict what’s happening on the other side of the wall by what you can see. I wasn’t even fully aware I was doing that at first until someone pointed it out. They said, “You know you’re exploring quantum theory physically?”

Langdon Graves, Presque Vu, 2016, Graphite and pastel on mylar

The exhibition not only explores the spiritual realm but also the ever-changing structure of memory. In particular, negative space becomes important–what isn’t remembered or seen. What is the role of negative space in your work?

I’ve always had an interest in how much information I can withhold while still allowing you to connect with what you’re seeing. It’s often the pieces that aren’t there that tell most of the story. When it’s very personal work for me, it leaves room for the viewer to insert their own meaning. There’s a loss to it–a loss of people and life, as well as a general feeling of loss as you age. I’ve been thinking about how there are things you lose and can’t get back. Your relationship with your family changes when you become an adult. You realize they’re flawed adults as well. It’s been interesting to get to know my mother, grandmother and other women in my family as people, not just as my elders. As they get older, you start to take on the role of mothering them and there’s a loss to that as well. The negative space in this show I think deals with that to a degree.

Also ghost stories and anything dealing with the unknown typically have missing pieces or something you can’t see. There’s a presence I don’t want to make material but I still want to be felt.

Despite being about ghosts and the supernatural, the exhibition features these pastel tones. What led you to choose this color scheme?

This is a palette I work with a lot and I also work with icky stuff very often. I was making work a couple years ago that were dissections of bodies in pink frames. Pink and yellow are these two colors that can go either way–yellow is happy and bright, but with one slight change, it’s a sick color. Pink is the same way. Pink, red and any type of inflammatory color is a warning when it comes to the body. It’s like, “Oh, I’m not supposed to see that or this isn’t supposed to be this big or that’s bleeding.” The pink I use is very close to the color that has been tested as an institutional pink used in correctional facilities and juvenile detention centers. It’s been studied as a color that produces calm. It’s womb-like so that’s not too far-fetched. It’s also this transitional color and has this intermediary sort of feeling. I teach color theory so I put a lot of pressure on myself to know what I’m talking about with color.

Langdon Graves, Séance (American Spirit), 2016, Graphite, pastel, paint, paper and mylar

Your grandmother’s stories are hidden within these ambiguous and unexplained sculptures, drawings and installations. Could you tell me one of her stories?

My grandmother’s father was a mortician and my grandmother also grew up in a convent. She was literally surrounded by death and belief in the afterlife whether she believed in it or not. The convent where she lived was actually where The Exorcist was filmed so it’s this famous, saturated type of place. When she was very young she saw bodies prepared all the time. Her Aunt Mary died when she was four or five-years old. It’s customary that the body would be kept in the house before the wake. She slept in her Aunt Mary’s room the night before the wake. In the middle of the night, she heard a noise, sat up in bed and watched a dresser drawer open. Two white day gloves just neatly folded themselves over the drawer as if being laid out for the next day. She said she smelled this waft of funeral flowers but she wasn’t scared. She just watched it happen and put herself back to bed. She said she found out the next day the gloves had already been placed on the body so they couldn’t have been in the drawer. The story is something that has stayed with her and very much with me.

Ghost stories and storytelling have a long Southern tradition, particularly within the Southern Gothic genre. Being from Virginia, do you see your work engaging with this history?

I do think that’s where my grandmother and my swapping stories–or my just absorbing hers–began. It was after we cleared the pie off the table quite literally. Things are more magical, a little more mysterious and a little more shrouded in Southern culture. I remember when I was a freshman in college I got really into Truman Capote. Capote’s writing describes the heaviness of the air, the hot temperature and the heavy trees. Everything is sort of shaded. He creates this air where you can’t quite see what’s happening. There’s a voyeuristic aspect to it and something hanging over everything. I think very much that’s an influence. I grew up outside D.C. but I lived in Richmond for ten years. Richmond is not as far south as some places, but in its mind, it is the southern tip of the United States. I think that influenced me aesthetically and with the storytelling.

Have viewers approached you with their own paranormal stories?

Sometimes when you work with the personal it gets picked up on. At the opening, this very pregnant woman came up to me with two friends. They had very thick Spanish accents and were visiting from Spain. The pregnant woman said, “I have to know about your title.” I said, “Sure” and I started explaining it. Her friends were looking at her and winking. Then she says, “I’m a physicist.” Oh, no pressure! As we got to talking, she revealed she was very superstitious. She did the whole spinning the wedding ring to find out if her baby was a boy or a girl and she has some things she wouldn’t do because she’s pregnant. It was interesting to hear someone who has chosen a particular perspective of the world based on their profession where everything is grounded in earthly explanation say, “I don’t always subscribe to this stuff and I don’t always understand it. Some things can’t be explained with science.”

Comments on this entry are closed.