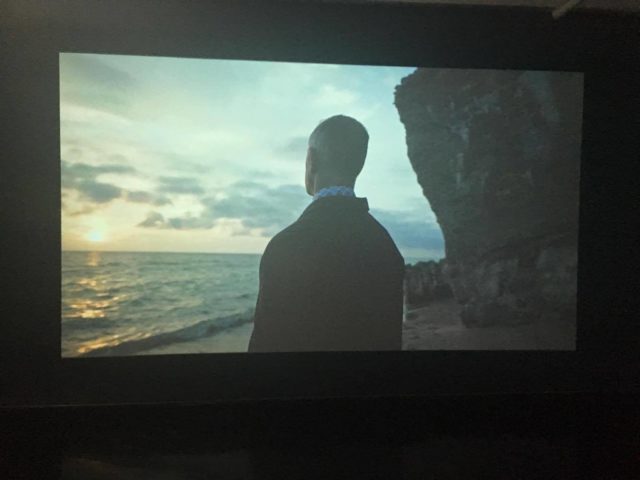

Ieva Epnere, Sea of Living Memories, (video still), 2016. (Courtesy the artist and kim? Contemporary Art Centre, Riga, Latvia)

Following the first part of my DUMBO gallery round-up, I concluded my waterfront adventure by visiting A.I.R. Gallery and Art In General. More on my trip below:

Yvette Drury Dubinsky: On The Move, Nancy Morrow & Erin Wiersma: With/drawn and Yun Shin: Filtering

Yvette Drury Dubinsky, CominggoingEurope, 2016, 28-inch diameter, Cyanotype, monotype and collage on handmade watercolor and Japanese paper (Courtesy the artist and A.I.R. Gallery)

A.I.R. Gallery

155 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY

On view until October 9, 2016

Non-traditional gallery models have their pluses and minuses. For A.I.R. Gallery–a membership based gallery founded with the intent to support and raise the visibility of women artists, one obvious perk is the ability to showcase the work of their members. On the downside, though, A.I.R. doesn’t have a curatorial model so much as it does an membership proposal process. Even with an exhibition committee, that pretty much ensures that the shows won’t all fit together neatly.

Take, for example, A.I.R.’s current lineup of fall exhibitions. Yvette Drury Dubinsky’s refugee-focused On The Move set such a high standard of sociopolitical relevance that the other two exhibitions–Nancy Morrow and Erin Wiersma’s duel With/drawn and Yun Shin’s Filtering–seemed like an afterthought.

Nancy Morrow, See you, see me, see you, 2016, WC, gouache, acrylic, and graphite on paper (photo by author)

This isn’t to say that the other two shows weren’t compelling in their own right. In particular, Nancy Morrow’s mixed media drawings, made in response to her partner’s struggles with dementia, powerfully translated the failure of memory to recall everyday objects and familiar people. Even Yun Shin’s obsessive and thick abstractions on carbon paper left you wanting to stroke the paper.

But, these work paled in comparison to Drury Dubinsky’s show. Part of this had to do with A.I.R.’s organization of the exhibitions. Viewers entered On The Move first before moving on to the other two shows. It’s almost impossible to transition to more formal aesthetic concerns after confronting a global humanitarian crisis.

On The Move takes Syria as its starting point, a particularly personal topic for the artist who visited Syria just before its civil war. Drury Dubinsky displays a series of mostly circular works on handmade Japanese paper. Each piece features a map, revealing a country or city whose population has endured some form of displacement. The borders of the mixed media collages are covered in mysterious silhouetted figures.

Admittedly, the works are cheesy. Maps and ambiguous refugee figures are not just simplistic, they’re cliché. But, sometimes, I can overlook a show’s cheesiness due to its politics. And the refugee crisis is certainly dire enough to give Drury Dubinsky’s art a second look.

Take, for example, Cominggoing Europe, which depicts layers of overlapping multicolored figures. With no faces or any discerning features, their shadows give no indication of race, ethnicity or country of origin. This undoubtedly deserves an eye roll for its “We Are The World” aesthetic. But, the figures do also engage with realities of displacement. The groups of amorphous figures are, on one hand, a representation of the universality of refugees. They could be anyone. And on the other hand, they are ghosts. Like the displaced are often treated in host countries, they are the unknowable and often, invisible other.

Drury Dubinsky doesn’t restrict her focus to Syria alone, expanding the show’s reach to other forms of displacement. The work New Suns, for example, places migration directly in the United States with a map of the Midwest. With both Chicago and St. Louis visible on the map–two cities where the artist has lived, the work references her own migrations. By tying her personal experiences to the political, she encourages viewers to consider their own moves– whether international, national or just within a city itself–within a global political context.

Ieva Epnere: Sea of Living Memories

Still from Ieva Epnere’s Potom (Later) at Art In General (photo by author)

Art In General

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY

On view until November 5, 2016

If Yvette Drury Dubinsky’s On The Move succeeds despite its hackneyed imagery, Latvian artist Ieva Epnere’s nearby exhibition Sea of Living Memories does the exact opposite. Despite her polished cinematic aesthetic, the show’s political resonance falls flat.

Co-presented with kim? Contemporary Art Centre in Riga, Latvia and curated by their own Zane Onckule, Sea of Living Memories deals with the instability of the Latvian identity after the fall of the Soviet Union. While an important subject to mine, the show alienates viewers who aren’t up-to-date on their Latvian history. I found myself researching Latvian politics on Wikipedia late at night after viewing the show to try and understand it.

The central piece in the exhibition is a 20-minute fictionalized film Potom (Later). Opening with a textured close-up of a Soviet-style leather trench coat, the film immediately introduces a sense of power and intimidation. It then sleepily follows a solitary older man as he gets dressed, does pushups, eats some ancient-looking bread and wanders aimlessly on a beach. With a droning soundtrack blaring menacingly throughout, Potom captures perhaps the most realistic depiction of depression since Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia.

More than its pervasive moroseness, the film references the Soviet-controlled military past of the Baltic coast. There are numerous longing shots of ports and ruined fortresses. The last shot in the film juxtaposes the older man’s isolation with the brotherly camaraderie of sailors’ skipping pebbles into the sea.

Even though I caught the overall contrasting nostalgia and trauma of Soviet rule, there were moments in the film when I felt like I was missing something. For example, I assume the ruined fortress on the beach had some specific historic significance, but I have no idea what that was. Instead, I only could relate to it in basic generalities.

One of the stacks of Russian military blankets in Ieva Epnere’s Sea of Living Memories (photo by author)

This feeling was even further emphasized in the next room, which covers the walls with photographs of coral, a tapestry of the beach landscape in Potom and two piles of blankets. The press release describes them as “material reminders of the Soviet legacy,” but it doesn’t give any means to understand why these are Soviet reminders and what they might signify. With some selective Googling, I learned the grey blankets are Russian military blankets, but in the gallery, I wondered if these were intentional or left over from the install. To me, these pieces didn’t seem to add anything to the show, but I suspect that was due to a failure of letting viewers in on the secret.

The exhibition reminded me of the New Museum’s 2011 exhibition Ostalgia, which wrestled with the same problematic of longing for the past Soviet control. The strength of that show illuminates the weakness of Sea of Living Memories. In Ostalgia, the New Museum wrote extensive corresponding wall labels, giving viewers a historical baseline of knowledge with which to approach the work. Art in General provided none of this.

To be fair, Epnere does show a series of short interview-style documentary videos in the last room of the gallery, which shed light on the strained transition of post-Soviet Latvia, as well as the romantic and familial relationships that make this division more complex. But after watching a slow 20-minute film, it is hard to find the motivation to sit and dive into the personal stories of Latvian citizens with limited context. Indeed even those who do make it through the narratives, may still find themselves seeking an answer key.

Comments on this entry are closed.