Lordes, “Yellow Flicker Beat”

In the video for Lorde’s anthemic pop song “Yellow Flicker Beat”, the young singer approaches a room stuffed with posh looking, and mostly much older, well dressed people. Men in tuxes and women in evening gowns make small talk and sip drinks. Lorde strides through the room, full of swagger, and then suddenly she falls down, falls over an unseen ledge, into a dark pit. The party goers carry on, never noticing her presence or her tumbling absence.

The first time I saw this video, I thought: I know that feeling. I have walked into those rooms, halls of power full of all the “right” people and then, however confident I might have felt upon entering, realized that I did not, could never, belong. And then I felt the floor open up beneath me. I am hardly alone. The arts have a way, a particularly cruel way, of making sure everybody knows the pecking order and thus where to set their beaks, big and sharp or tiny and soft.

2016 was a difficult year for practically everybody: Syria, an endless stream of beloved artist/celebrity deaths, the now-universal realization that acclaimed “creative class” hubs have become inaccessibly expensive, the menace of an increasingly aggressive authoritarian regime in Russia, the planet set on boil, that poor gorilla shot to death in a zoo. Trump. In my native Canada, a scandal erupted in the arts that lay bare (many, myself included, would say finally laid bare) the real politick of the arts in our supposedly cuddly and cosy nation. The details are less important than how the event played out, but let’s just report that one group of very well-known and well-rewarded literary artists, in an attempt to protect one of their own from a growing collection of accusations of misbehavior, constructed a public pile-on in an attempt to smother a group of much less known and utterly without reward emerging artists, namely the ones lodging the accusations.

It was ugly and nasty and quickly grew from a case of one special interest group attacking another to a cause for national alarm. Why “national alarm”? Because, as many commentators noted, it has always been supposed that The Arts, being a lofty and allegedly selfless pursuit, were above such claw-wielding and fang-baring. If only. I’m sorry for anybody caught in that quagmire, but to have such inane mythologies about life in the arts finally and irrevocably exposed was worth whatever damage was done to the participating individuals.

The fact that this scandal played itself out in a rarefied environment and was minor, slapstick minor, in comparison to world events and catastrophes, only makes the incident more telling. What we learned, and what all arts professionals can subsequently learn from this squabble, is that no stakes are too small and no careers too obscure in the arts to not prompt a vicious power struggle.

2017 will mark my 25th anniversary in the art criticism/cultural commentary game. I’m no smarter than I was when I started writing about art and culture, but I’ve seen much more, and if I have a wish for 2017 it is that we start to talk about arts and culture in a more forthright manner. And that conversation can only begin when we talk about power.

The arts are like any other industry, and yet we persist in using terms like “art world”, or “community” as if we are not in constant competition, not always struggling to do better and get more, not trying to become more famous and acquire power. Artists are no different than people who work in, say, banking or mining or wedding planning.

But because we over-invest the production of art with all kinds of flights of fancy coded with mystical narratives describing inspiration, talent, universalism, the human spirit, creativity as cure, etc., we are reluctant to acknowledge how careers are actually made. Careers are made by the skillful manipulation of social contacts, self-positioning, and the ability to make other artists feel that they and their works inhabit a different, lesser sphere than we and our works do. But what about talent, you might ask? Talent is skill plus agency. Skill without agency is hobbyism. That’s unpleasant but true.

I am not innocent here. I have said no to plenty of writing gigs I felt were “beneath” my status. And I know that if I don’t have those sorts of conversations with myself, chats about where I belong on the ladder, and then make choices based on that self-generated status, I will end up with no status at all. Power in any profession is acquired, taken, not bestowed. You take and keep taking, because to be seen to be empowered in the arts is to be empowered in the arts. Here’s an example: one of the key players in the literary scandal described above is now embroiled in a scandal relating to his personal life. When this story started making the rounds, I noticed an alarming number of comments in social media asking, “It is OK now to admit I don’t like his writing?” as if it was not “safe” to say so before.

People were right to be hesitant to criticize the work of this artist in the past because as a well-rewarded artist he had, and probably will continue to have power. His jury work and his presence on many arts boards and lobbies, as well as his deep connections to the “top” editors and publishers, could easily stall a career, block a grant application, or keep a less well-known artist from climbing the ladder. He got famous and he took power, by means both practical and then, as those were enacted, in his self-presentation.

Of course, who gets to take and who does not is where the real conversation about power in the arts needs to go next. If this doesn’t happen, if we continue to get caught up in our magical narratives about inspiration, talent and the human spirit, then we’re all just a bunch of white men talking to each other.

The way we talk about art making lacks grit, hard honesty. People make things in order to show them to other people. When other people look, approval and disapproval are at stake. From that moment of looking, a power dynamic begins between the thing observed and the observer. And then the whole nasty, muddy, grasping and tearing mess that is a life in the arts begins.

If we can get one good thing out of 2016, let’s take the bald truths of power struggles we have watched play out so thoroughly in other realms and apply them to the arts. First, let us acknowledge that artists want power, the ability to shape their own careers and then the careers of others, as much as people do in other industries. Second, just as people behave in other industries, artists and cultural workers are capable of a ruthlessness that would make any politician clap their silky hands with glee.

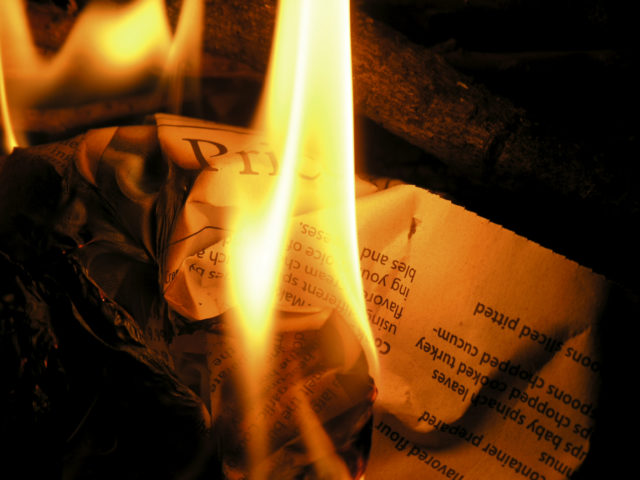

The path forward is harsh and unwelcoming; perfectly in synch with the real world of the arts.

Comments on this entry are closed.