David Claerbout, Sections of a Happy Moment, 2007

We've gotten better at time. Though a recent study has confirmed we can't beat it, the flash-freezing of photographic documentation and the temporal control of video has brought contemporary time (if such a thing can be identified) a long way from the immutable march of the everyday. In the arts, we've discovered an ability to expand and contract time as it's lived, and moreover we've learned to communicate that ability – to make the variable internal perception evident in phrases like “time flies when you're having fun” into a problem, a challenge, and rich ground for artmaking. Hence, the continuing relevance of shows like Fragments in Time and Space (through Aug. 28th), an exhibition from the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. that aims to “demonstrate the diverse ways in which time and space have been conceptualized, employed, and manipulated.”

The show opens with Ed Ruscha's Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966), a series of photographs taken on a section of LA's famous roadway from the back of a moving pickup truck and then stitched together. It's a gesture that's difficult to see today without thinking of Google Streetview, and might risk being overshadowed by Streetview's greater scope were it not for its simple length – rather than seeing the street one snippet at a time, we see it as a single, continuous presence, wrapped around itself to fit into its vitrine. Streetview gives the work a newly-heightened relevance and universality, without subtracting from Ruscha's contradictions: these are images of the same time, but also different times; of absolutes, but also the relativity of the camera's position; of stillness, created through motion. It's a little shocking, actually, how well it holds up, and it's an excellent curatorial gesture to demonstrate the continuing changes in our understanding of space.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, "Akron Civic, Ohio", 1980 Gelatin silver print on paper sheet: 19 7/8 x 23 7/8 in. (50.5 x 60.6 cm) image: 16 9/16 x 21 7/16 in. (42.0 x 54.5 cm)

On the same wall, we find a series of Hiroshi Sugimoto's long-exposure black-and-white photographs of movie theaters, each taken over the course of an entire film. In each, the screen becomes a solid white, surrounded by the rich architecture of carefully-chosen old-style palaces of cinema, named in each work's title; place is specific, but time is nonspecific, even immaterial. It has passed, and that is all: an appeal to sentimentality always requires a certain broadness of subject.

Across from these two works is the first of three small canvases on show from On Kawara's Today series, which mostly raises questions about whether work can fit a curatorial theme too well. For Today, Kawara paints the date in white lettering against a monochrome grey background; the works are packaged with newspapers from the artist's location on the specified day, and are always begun and completed before the clock turns over (incomplete paintings are destroyed). Kawara makes time and place into objects, turning the continuous into the discrete; fair enough. Compared to the other work on view, though, the paintings look weak: once the exhibition's conceit is set forward, every photograph and every video takes on the properties of these paintings, causing them to feel stale. Perhaps that's simply a risk of creating such straightforward work.

After the first room, it's a long stretch of bad art and bombast before one arrives at John Gerrard's Grow Finish Unit (Eva, Oklahoma). Grow Finish Unit is a painstaking recreation of an unmanned pig farm (or “production facility”, as the terminology now goes) in a video game engine, with maniacal amounts of detail and a real-time 365-day cycle. In the real-life version of these facilities, the pigs are fed automatically, their waste is removed automatically, and the only necessary human contact consists of a series of trucks brought every few months to replace the “finished” pigs and take them away for slaughter. Gerrard insightfully translates this into the medium of video game worlds, thereby rendering one automaton through another; the choice of tool easily and powerfully makes the cool machinations of modern agriculture clear. Meanwhile, the real-time cycle of the simulation is synced to the actual time in Oklahoma, so its progression gives it a level of reality beyond the visual; the “That, there it is, Lo!” of photography but also, “This is happening right now.” It's a clear standout in the show because it moves beyond the questioning stage of duration as form and into fluency: Gerrard doesn't need to question his tools, only to use them, and he does so adeptly and directly.

Takahiko iimura and Arata Isozaki's Ma: Space/Time in the Garden of Ryoan-Ji, is more problematic, but interesting for both its successes and its failures. The work is a video consisting almost entirely of iimura's long, achingly deliberate tracking shots of a Zen garden in Kyoto, occasionally interspersed with bits of Isozaki's poetry like “Perceive not the objects / but the distance between them / not the sounds / but the pauses they leave unfilled”. iimura and Isozaki describe “ma” as the “distance between two points or two sounds”, pointing to it as single word which collapses space and time in Japanese thought, and also as an aesthetic particularly present at Ryoan-Ji. That's far from bulletproof as a concept — one could easily argue that Western languages just as commonly use terms of space to describe time, and tellingly a term, nihonjinron, exists to refer to Japanese thoughts on their own peculiarity. That said, it's a fitting contrast to Ruscha's work; where in the former, the camera is a slave to the tick-tock-tick of everyday life, here the slow spatial passage of the tracking shots at once demarcates its own time and highlights the timelessness of the garden. Ruscha's work causes us to wonder what happens next, what happened before, what changed between the first image and the last; in Ma, the camera seems to document only a single moment, in exhaustive detail, despite our knowledge that film always means time's passing. That said, by committing the garden to film iimura and Isozaki impose on it an endpoint, a point at which, with the rolling of the credits, the viewer can stand thinking, “I have finished this.” It's a property that short-circuits the garden, overwhelming the timelessness Isozaki's words attempt to convey; in this, it could just as easily be an ironic gesture, but there's no hint of that here. Where works like Nam June Paik's 1962 Zen for Film, an eight-minute reel of blank film run through a projector, successfully bring the properties of the Zen garden to the gallery, iimura and Isozaki unwittingly ensure it is always contained, separate, elsewhere: peace stays in Kyoto.

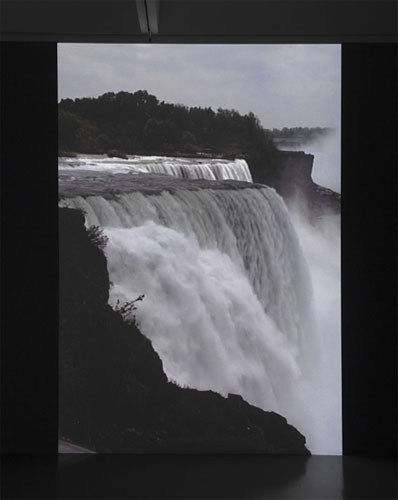

Wolfgang Staehle "Niagara", 2005 Video projection transferred to DVD running time: 00:60:00

Wolfgang Staehle's Niagara (2005), in the final room of the exhibition, accomplishes more. It's a simple 60-minute video of Niagara Falls from one of the common, picture-postcard vantage points; Staehle, though, loops the video, causing the waters to rush endlessly on the gallery wall. Though it's not real-time, as Gerrard's work is, the same feeling is elicited: this is happening now. It's a capturing of the past but also an undeniable fact of the present, and achieves the same grandeur and awe of seeing the ceaselessness of the Falls in person. The work is an excellent representation of its subject, though it struggles to be anything more.

Perhaps Sections of a Happy Moment (2007), David Claerbout's durational slideshow, is a more effective counterpoint. It's made up of black-and-white images from dozens of angles of a single moment, delivered slowly under a nostalgic-sounding easy-listening piano piece. The scene itself is sugary-sweet, of children playing with a ball outside an apartment block, watched adoringly by smiling parents and grandparents; frankly, it's content that's difficult to take seriously. It's hopefully more a joke about wanting to “make a moment last forever” than a serious gesture, but it hardly matters: the construction of the slideshow itself is what's on view here. It's striking, really, how rarely we see the same precise moment from two different angles – it's a curiosity that might be endlessly problematized, whose potential powered Cubism for years, and yet now that it's possible we reserve it only for close plays and stolen base attempts. Whatever the novelty of multiple angles, Claerbout moves beyond, organizing his images in resistance to the medium of video. With each fade-out and fade-in, we expect progress, change, some indication of time's passing; instead, again and again, we're served yet another take on the same. Video's role in the everyday is more often than not a speeding-up: quick cuts, 15-second ad slots, and the compression of the day's events into segments timed to the size of cereal bowls. By rejecting that, Claerbout's work comes far closer to Zen than anything in Ma.

The problem with manipulations of time and space as a theme – beyond, perhaps, the applicability of “manipulating space” to a majority of art practices, which renders it mute in the present show – is that we are too familiar with them. They're basic elements of our existence, and we are fully aware of the feelings of vertigo, meditation, or confusion their altering can affect. When they're manipulated well, we know, instinctively, inarguably, in a way that can't be finessed like the nuances of linguistic, political, or visual discussions in art. Given the immediacy of some of the works on view, it's difficult to take seriously works like Mark Tobey's Fragments in Time and Space (1966), an ethereal lavender abstraction in fidgety gouache with little power; even less so, works like Ma that claim power over time and space but then exert it imperfectly. In short, when works in this area fail, they fail hard, and Fragments in Time and Space becomes disappointingly hit-or-miss. Spend time with the show, by all means; spend it slowly, quickly, or in real-time. Just ensure you spend it wisely.

AFC's Rating: 6/10 (Will Brand)

{ 2 comments }

Great assessment of On Kawara!

His work often suffers in context because of the way it bangs out exactly the idea the curator wanted to illustrate. Like a kid in class who has very little original to say, but always has the right answer.

Truly a work of art.

Comments on this entry are closed.