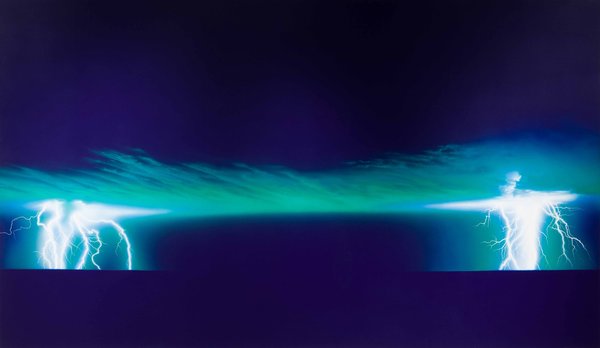

Jack Goldstein, "Untitled," 1983. From the Jewish Museum's current exhibition, "Jack Goldstein x 10,000".

Every once in a while an artist’s talk comes along that’s as spirited as a wild dinner party. The conversation’s good, if a little off track, but mostly, it’s the company that makes the evening worthwhile. That pretty much sums up what happened Tuesday night at the Jewish Museum’s “Dialogue and Discourse: How Is Jack Goldstein?”, a roundtable held in conjunction with the Jewish Museum’s current exhibition Jack Goldstein x 10,0000.

The on-stage guests consisted of artists R.H. Quaytman and John Baldessari, and moderator Jens Hoffmann, the Jewish Museum’s Deputy Director. Of the panelists, Baldessari was the only one with a personal relationship to Goldstein; he came out of the artist’s first crop of students at CalArts.

That didn’t prevent everyone from having their own personal takes on the artist’s lasting legacy. For the most part, the talk didn’t stray far from attempts to figure out the difference, if any, between Goldstein’s life and work.

“[His] big drama was trying to get ideas into the two-dimensional,” R.H. Quaytman began. “His images were banal, but also melodramatic. There was a fear and danger.” Hoffmann went on to reiterate that viewpoint, saying there’s “a fascination with something dark that you’ll see in the early paintings and then later in the natural phenomena. But at the same time they have a beautiful quality at the same time they’re horrifying.” Baldessari, a lone wolf, wryly disagreed with any of those readings.

When Quaytman brought up how Goldstein’s military brat lifestyle influenced his work, with his father in the military, Baldessari cut in.

“There was that trauma there,” Quaytman said. “Obviously of World War II.”

“I really try to avoid those readings,” Baldessari said abruptly. “I catch myself in those readings and I really hate myself..but it sounds good!”

Quaytman continued to explain Goldstein’s contribution in terms of the artist’s self. “There’s no self in his work, and I think that was the goal that was so fierce and violent,” Quaytman said. “Though I wouldn’t have really wanted to know him or anything.” For Quaytman, the type of self in Goldstein’s work, was really an anti-self; she applauded his use of appropriated imagery and outsourcing the actual painting of the paintings to others. Evading any talk about the psychology of art practice, Baldessari referred to this method as “finished finish”. “Finish is so embedded in L.A. culture,” Baldessari said, “He was trying to avoid any trace of the brushstroke.” The artist then rattled off a list of California ornamentation that prefers the “wax on/wax off” effect: cars, surfboards, skateboards, and of course, paintings. For Baldessari, that list points to Goldstein’s’ lack of a singular legacy; he was just one of many artists working in California at the time who were trying to avoid the brushstroke.

Coupled with other remarks hinting at Goldstein’s menial ranking, the artist’s former student doesn’t seem to shine so brightly in Baldessari’s eyes. “Jack wouldn’t have stood out so much if he hadn’t committed suicide,” Baldessari actually said. “Talk about this artist myth we buy into!” Baldessari went on to say that Goldstein’s best work took place early on, in 1972, when he was buried alive as a student at the CalArts campus. So much for a lasting career.

Comments like these were just as often refreshing as they were off-putting. At the very least, they provided a nice counterpoint to the praises of Quaytman and Hoffmann. By the end of the hour-long discussion, the only consensus reached by the panelists was summed up by one of John Baldessari’s closing remarks: “Nobody knew who Jack Goldstein was.”

Comments on this entry are closed.