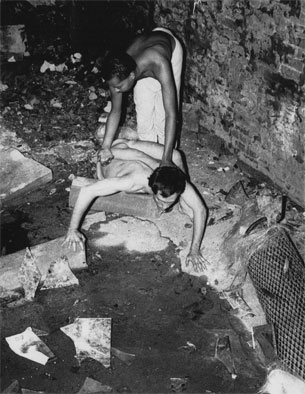

Gordon Kurtti shooting Leslie Lowe and Kembra Pfahler in Leslie Lowe's "Persephone" (Image courtesy of the Gordon Kurtti Project)

In the scope of New York City history, seven years isn’t much time. For the East Village art scene, though, it was a lifetime, and for artist Gordon Kurtti, it was an entire career. After a brief but bright formation in the East Village performance scene, Kurtti passed away in 1987, at age 26, of AIDS-related complications; twenty-six years later, a mini-retrospective at Participant Inc. acquaints us with his life and work. It’s an intimate memorial for Kurtti, but it’s also a story of community, and the meaning of comings and goings.

On the surface, the Gordon Kurtti Project deals us a needed political reminder, and suggests that the lost generation–conspicuously, the queer avant-garde–left behind still unrecognized contributions to art and culture. Had Kurtti survived to the present, he would have had another twenty-six years (in his case, another lifetime) to impact his friends. In only seven years of living in New York, a few of which spent in art school, he’d already formed lifelong bonds, namely with his close collaborators Kembra Pfahler and Allied Productions.

Those relationships are remembered here in a handful of photos on the website, and beautiful catalog essays by Cynthia Carr and fellow Allied members Jack Waters, Peter Cramer, and Carl George. They shared concentric circles with now-canonized names like Kiki Smith, Jenny Holzer, Karen Finley, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, David Wojnarowicz, etcetera, etcetera.

The reading material roughly sketches the character of a long-dead scene: artists writhing in basements, playing Dionysian gods in the woods, smoking cigarettes, kissing, looking like movie stars crossing the street. Their energies are probably best encapsulated in their 1983 performance marathon “Seven Days of Creation,” and “The Extremist Show,” which the crews staged at ABC No Rio–where, as Allied Productions notes in the catalog, artists never went to bolster their resumes. It was a place for experimentation, and quite possible failure.

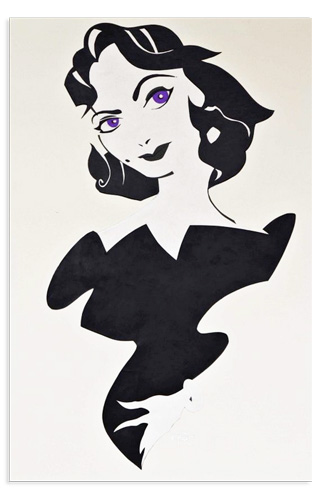

Still, it’s impossible to say where Kurtti might have taken his career in the next lifetime. He was an avid caricaturist, minimally depicting 80’s celebrities like Anita Baker, Elizabeth Taylor, and Prince, though hadn’t quite developed a style. The lines are a little too rounded, and with a traced-over quality that hadn’t yet matured to big risks. More range can be seen in caricatures of his fellow Allied Productions members; Waters’s wispy eyes are treated fondly with a light colored pencil, and lightning strokes for George’s watercolored profile. A small “Happy Birthday” note is scrawled in the bottom corner of Cramer’s. The love is touching, but like the photos on the Gordon Kurtti website, they depend on anecdotal information which may make them difficult for outsiders to fully appreciate.

Instead, the Gordon Kurtti Project comes to life in “One Night Stands”, the community performance evenings, and the first of which featured writer Joe Westmoreland, poet Eileen Myles, and artist Kembra Pfahler. Westmoreland and Myles gave long readings from chapters of their books, both, eloquently sad reflections on the beginning of the end of the AIDS crisis. From Tramps Like Us, Westmoreland read his chapter “Underwear Party“–or, he added, “How I Caught HIV, Version 512.”

The chapter, read in Westmoreland’s deep murmur, paints a picture of a cozy evening in 1986 in San Francisco when close friends lowered the blinds, shot some dope, and snuggled up in boxer shorts. The scene feels about as warm and innocent as a Norman Rockwell painting, with short, direct sentences that make us think only of the present. For a while, Westmoreland offers a taste of sweet freedom from our contemporary fears about other people’s bodies. But by 1986, the AIDS crisis was well underway; their friends went home, and the writer’s left debating whether to have sex with his friend Ali, who’d just returned to the hospital between bouts of illness. A glimpse of Ali’s IV scar registers dread. He figures it’s okay, though, because they’d already shared a needle.

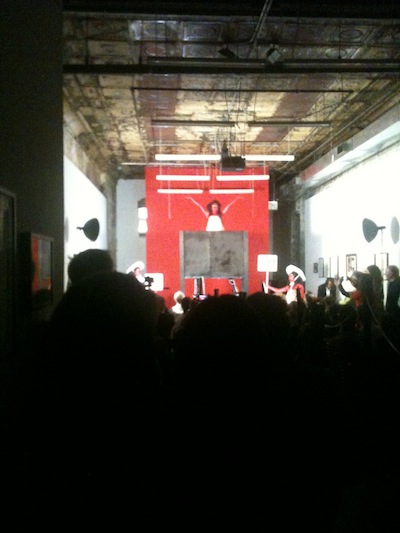

Fellow "Allied" members Jack Waters and Peter Francis performing at dawn in the back yard of ABC No Rio, as part of the 1983 "Extremist Show" (Image courtesy of ABC No Rio Dinero)

The scene pictures early fears, but not the full shock and horror after people started dying, as captured by poet Eileen Myles in “Moving”, a chapter from her novel Inferno. It’s beautiful, and lonely. “I came to understand that I was now explaining the world to a sad child which was me” she read, “and I would find her things and try to make a story for her out of what I picked up.” To that end, “Moving” presents a glazed-over disconnect from finality, as told by a sleepwalker mulling over memories:

Paul died when everyone did, of AIDS. I had learned about it in Nan’s video at the Whitney. Someone just casually said it, walking down Commercial. Now everyone’s dead—Paul Johnson …I felt I was here to visit him. I remembered seeing him so long ago in Cambridge. He was driving a cab. He told me about P-town and he just looked manly and large. Like that was pleasant for him. It seemed like he was “just working”—isn’t that throwing your life away, I thought.

But in fact he was fishing and having sex and then he left P-town for law school and fought for tenant’s rights. In college he was a skinny fag. In college he was bi.

There’s no great closer to that thought, which seems to be the point. The chapter contemplates endings–to relationships, poems, trips, lives–which you can imagine might be a fixation, watching your friends disappear. Myles even interrupted herself to add: “That’s what’s so weird about time, when I think about the nineties or the eighties, I was feeling old. And then like twenty years passed, and I’m like, so what is this?” And then the chapter itself contained several false pauses before Myles finally put the book down. When she did, though, you’d want to let that moment land.

But soon, sundown became an after-hours party, and the audience doubled just in time for Kembra Pfahler. She and her Voluptuous Horror girls staged a very early performance, which, you can guess from Cynthia Carr’s catalog essay, is a Kurtti-less version of a pre-Voluptuous Horror collaboration. Carr describes a night at the Pyramid Club, where they climbed into a raised black box; Gordon spewed down from Kembra’s legs, showered in thirty raw eggs. At the time, Pfahler explains, “We were beginning our lives again as artists.”

This version had the Karen Black girls dressed in cardboard sunhats and checkered onesies, marching in with “1984” picket signs to a high school musical-like piano verse. The piano turned into a drumbeat, and again, performers crawled up into a raised black box. This time, they swung their legs down and chanted “Availabism is: making the best use of what’s a-v-aaai-la-ble,” a statement of Pfahler and Kurtti’s DIY philosophy. Like anyone taking their first steps, and without a climax, the legs dangled awkwardly. The show ended abruptly with a “Yeah, that’s it”, wrapping up the night, perfectly, with another unceremonious ending.

Comments on this entry are closed.