9.5 Theses on Art and Class, by Ben Davis, editor of Artinfo, is both victim to and substantiated by Davis’s adamant worldview. Beginning with the Marxist-centric essays of the early chapters then expanding to more general issues facing the art world, the text saves itself from being an open-ended musing by framing each subject within its relationship to class ideology. This same ideology, however, leads him make some less than irrefutable claims—that all art criticism needs to consider politics or that political art is a lazy shadow of activism. As he writes: “ As a critical trope, ‘aesthetic politics’ is more of an excuse not to be engaged in the difficult, ugly business of nonartistic political activism than it is a way of contributing to it.”

As a collection of essays, 9.5 Theses is simultaneously diverse and thorough. Each chapter checkmarks an item on the list of problems facing the art world today, from women’s under-representation to the hipster aesthetic to the tension between conceptual artists and traditional artists.

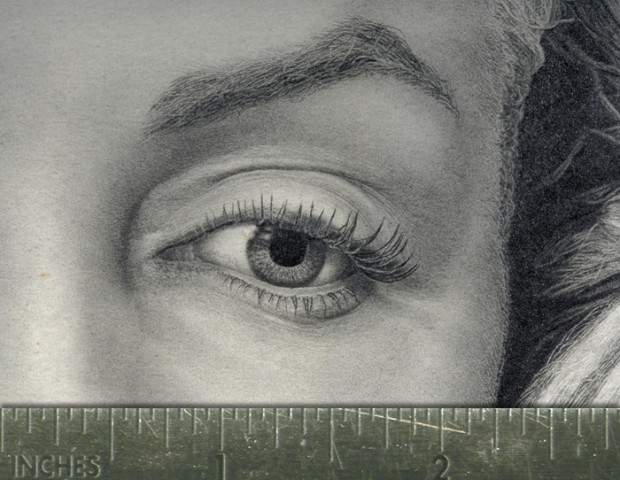

Especially strong is Davis’s elucidation of contradictions embedded in “insider” perceptions of artistic culture. In the Chapter “Agony of the Interloper,” he discusses the film Waiting for Hockney, a documentary following the artist Billy Pappas as he creates his hyper-detailed replica of a Marilyn Monroe photograph by Richard Avedon. Pappas believes the drawing will skyrocket him into the upper ranks of the art world based on technical skill alone, but it is ultimately spurned by his idol, David Hockney. Davis calls this “both a testament to creativity thwarted and to creativity redeemed … because it [the drawing] is the product of a society that creates contradictions for how we view art.”

Some of Davis’s claims, however, are a little less than airtight. In the chapter “Beyond the Art World,” Davis contends that the term “art world,” though convenient, is dangerous. I didn’t have much trouble agreeing with this, except that Davis jumps immediately from that to the idea that art and societal structure must be united. He begins the chapter with “Art is not a world unto itself. Art is a part of the world,” and quickly moves on to say that “you should approach art politically,” which, granted, “is not necessarily the same as demanding that art be political.”

Those qualifications are necessary, but this need for a political approach to all art nonetheless leads to the bigger fallacy that politics is a synonym for the world. Everything seems to be built upon the assumption that ignoring the role of politics is tantamount to isolating art to a constant reflection of itself. While I can agree that, when art ignores the world, it makes itself obsolete, this does not mean that art must concern itself with class relations.

Also, Davis claims that 9.5 Theses is written both for ”artists, writers, and other art lovers” and the “political audience looking, from the outside, for some kind of sympathetic guide to…contemporary art”, but I’m not so sure. It’s true that, as a text, it’s beautifully devoid of jargon. The language is pithy, the logic linear, and the points are illustrated in numbers and examples rather than left to blanket statements. However, though it may be perfectly understandable to a politically-minded person, there’s little justification for why such a person would care to read the text. We never learn why the art world is relevant to a lay reader. Davis could more explicitly say why political people should care about artists as citizens, even if it’s just that artists are part of the workforce.

That said, everyone would benefit from reading the eponymous “9.5 Theses on Art and Class” pamphlet, chapter 3 in the book. Using clear, linear logic, the pamphlet spells out Davis’s view of a better artistic culture (e.g. “3.0: Though ruling-class ideology is ultimately dominant within the sphere of the arts, the predominant character of this sphere is middle class” and “5.0: The idea of ‘art’ has a basic and human sense on which no specific profession or class has a monopoly”). That it was a valuable text is undeniable: it actually allowed me to understand what Davis means when he talks about the artist’s struggle within their class.

If nothing else, 9.5 Theses is absolutely worth reading. Even where Davis did not win me over to his way of thinking, he certainly forced me to strengthen my own. None of what he writes can be immediately discarded. Furthermore, Davis avoids the major Marxist pitfall of starting with some utopian ideal; instead he focuses on how people can behave today, offering productive, applicable insights, rather than starry-eyed dreams.

Comments on this entry are closed.