This interview series is produced in partnership with MATTE Magazine, a publication produced by writer and curator Matthew Leifheit that focuses on the work of a single photographer per issue.

Even those unfamiliar with Elisabeth Biondi’s name have probably seen her work. Until she left The New Yorker in 2011, she had been their photo editor for fifteen years. Prior to that, she was the photo editor for Vanity Fair. And before that, she was the photo editor for Geo, a German magazine with a focus on geography, history, and world culture that went out of business in the 80’s. For this interview, I talked to Biondi about what it was like to work with photographers like Annie Leibovitz and Helmut Newton, what life at The New Yorker is like and how photography has changed since she got in the game. The short answer to that last question: video is going to have a much bigger presence in the future.

I’m interested in your path in general. You grew up in Germany, in a small town, right?

A village. 200 people, 400 cows.

When did you become interested in photography? Was it then?

No. There was nothing there. And my parents were not interested in art. So I quite frankly don’t really know how it started. At 19 I was an au pair girl in Paris. It had nothing to with photography, but I would go to museums. I’m a total autodidact, everything I’ve learned I taught myself.

I married an American in Germany, and then we went to New York. I took a job in a tiny commercial photo studio. I was the assistant to the guy who ran it and I had to type letters, which was terrible because I didn’t know then what I know now—which is that I’m dyslexic.

While I was there, I decided I wanted to do something with photography. I wanted to be a photo editor. I thought, well I need to be hired by a magazine. Since I had no experience, I could not be hired by a good magazine. So I was hired by Penthouse.

Penthouse in the 70’s must have been a trip.

I went to the house the first day in my little suit because I thought it was a proper thing. But what I was really doing was finding releases for photos of the Penthouse Pets centerfold photos, and organizing them so they could be sold commercially. It took me two years, and then I was hired by Geo Magazine. Geo is a German magazine, and they were going to come out with an American edition. To me, that’s when I really started to learn about photography. I loved it so much, that when there was a holiday, I was just upset because we couldn’t work. And this came at a time when I was divorcing my husband; I was starting a new life, and it was perfect timing.

The Executive Editor was Thomas Hoepker, who is a Magnum photographer. I learned everything about photography from him. The rules were to respect photography: Not to crop. No type over the image. You respect the story, but photography is independent, it has its own entity, it is parallel to the text but does not illustrate the text. To this day I follow those rules.

These were the glory days of magazines. We would assign a photographer, and they would go out on assignment for three or four weeks, sometimes with a writer. Our offices were in a penthouse on Park Avenue, and we produced a very beautiful magazine, on heavy stock. In the first issue we did a story on the Badlands [National Park], and there were 20 pages of photos. It was expensive, probably equivalent to $16 today. There were lots of problems with the business plan. We had a disastrous series of editors-in-chief. There was a dip in the economy and money was short in New York, and the magazine was shuttered.

So you needed a job.

Tina [Brown] had recently become editor-in-chief of Vanity Fair, and at that point it was unsuccessful, a mess. I walked into the office the first day with a big black bag, and in it were six rolodexes. And that was my pride—my rolodexes with all the addresses in it! Eventually Tina realized they should have a functioning photo department, so she made me Director of Photography. I wasn’t reporting to the Art Director, I was an independent entity.

The magazine started to catch on. I have to say Tina was the right person for that time, for that magazine. She was gutsy. She was very hard to work for; it was hell because she changed things constantly and we worked horrible hours. But it was her magazine. So you put up with her incredible demands. With Tina, “no” is not an option. If you said something couldn’t be done, you were ignored. So what I learned from her is to attempt the impossible. Even if you fail, just try.

What photographers did you work with during that time?

Well, Annie Leibovitz was the staff photographer. She was Vanity Fair’s photographic face. Annie basically created the look and the tone of the magazine. She was part of the reason the magazine was successful and Tina very quickly recognized that.

We got every big photographer: David Bailey, Bruce Webber, Herb Ritts, you name it. One day Tina called me into her office and asked me to organize a shoot for Helmut Newton. So Helmut came in and he was totally snooty, and dismissive of me. And I got really angry. So I said, “What is it you want? I gave you the information, what have I not given you?” I stood up to him because he was German and I knew I could. So from then on, we became friends. I worked extremely well with him.

The amazing thing about Helmut was the way he worked. It was very opposite from Annie. Annie wanted a staff of fifty and lots of film. Helmut wanted one assistant to drive the car, required a good hotel, and he usually shot just a couple rolls.

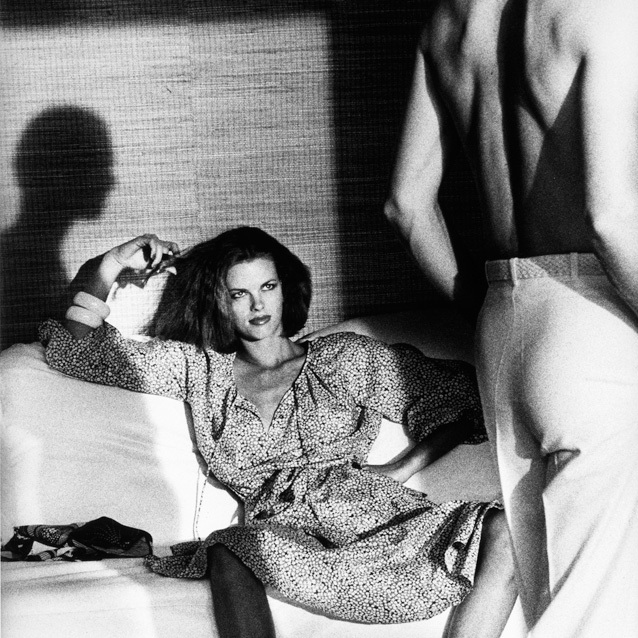

He was famous for photos of women, but actually his pictures of men were very good, too. I have a picture of his, where a very attractive model, a woman sits there like a man, with her legs spread. You see the ass of a man going by, and she’s like “Oh, not bad!” It was a total reversal. I think Helmut was misunderstood. All his women are very strong.

”]

How long were you at Vanity Fair.

7 years. I left in 1991. The Iron Curtain went away, the wall went down, and it was an incredibly exuberant time in Europe. It was May, I was in Berlin, we thought it was the new world. I got myself a job at Stern. I stayed for five years, there were good and bad things about it, but the main thing was that I didn’t like living in Germany.

A friend of mine from America was celebrating his birthday in Florence. I was there, and the phone rang, and Tina was wondering if I might consider coming back to America. I covered up the receiver and jumped up and down with excitement.

In the meantime she had become the Editor-in-Chief of The New Yorker, and you wound up running the photo department for the next 15 years.

They had no proper photo department at that time. This was 1996. We worked with one staff photographer, Richard Avedon.

What was working with Avedon like?

You didn’t really work with Avedon. He produced his own pictures. I think it was incredibly smart for Tina to get him. Whatever she paid him, it was worth the money, and no one could fault her.

Tina realized she needed more than one photographer, and so I was hired to organize a photography department. The great thing was that there was no tradition, so I could create it. I thought it would be easy, there were so few photographs in the magazine. Of course it wasn’t: How do you do pictures for a magazine so well known for its text?

Tina was very adventurous. She had been asked to revamp the whole magazine. There were writers with offices who never came in. It needed to be run in a more contemporary way. So the magazine had to become less genteel, and this created a lot of resistance. It was a rough transition.

What was your vision for photos in The New Yorker?

I feel the pictures have to be strong. You have very few pictures, so they have to have an identity on the page. And they have to be smart, and you have to put editorial content into the pictures, but not in an illustrative way. The pictures have to make their own statement that is somehow connected to the text. And that’s very difficult when you only have one photograph. So you have to work with photographers who think about things, and don’t just take nice images.

I rarely went to shoots because I didn’t want to go to shoots. I picked the photographer because of what he or she does well, and I gave them all the information, so he could do the kind of picture that he wanted to do for the magazine. It’s like a sandbox: I give you the outline, and you’re now in the sandbox, and you can build the sand castle.

Personally I’m interested in the point where documentary aspects of photography and art photography meet. I want to look at visually stimulating photography, but that doesn’t mean I want pictures of roses blooming. I want my eye and my brain to be engaged, not just one or the other.

Has the magazine world changed?

Well, I fell into this [at the right time]. At a certain point I knew the direction I was headed, and took charge of it. Since I have stopped working for magazines, I am realizing how lucky I was in terms of the time I worked in that world.

Right, it doesn’t seem like you could do this now. Like, you didn’t have to do an internship.

No! I still get people asking me how I did this because they want to be a photo editor. And I say forget it! It’s changed. It’s a different time, and magazines take a different shape now. The traditional structure doesn’t work any more. Also, autonomous photo departments rarely exist. They usually answer to a creative director. Now, there’s a creative director at The New Yorker.

Now I think video is going to get stronger and stronger. It’s just part of visual life now. And magazines have to make different platforms that can support changes like these.

You left The New Yorker two years ago, and now you’re doing whatever you want?

I had a very full professional life, and was of a certain age, but I didn’t want to retire. I feel strongly that I was very fortunate in my career, so at a certain point, I’d like to give something back. So instead of going to give out meals on Thanksgiving, I help young photographers. I really want to work with young people—it’s like my pro-bono work.

I don’t make much money, but fortunately I worked for a company that has a pension. So that affords me the luxury of doing some work that is not paid for. I always had a young photo department, a staff that is many years younger than I was, and I really felt that’s the way I can keep things fresh. I still believe that.

Comments on this entry are closed.