Painting may have never reflected the life and culture of New York City more closely than it does now in the sense that both have the feel of an epicurean walking tour. Whereas you can go through the Lower East Side sampling dim sum, chicken and waffles, and Bavarian pastries, lately the art world’s been offering its own form of culture-sampling: a handful of karaoke-themed shows, “Painting and Flowers,” “PIZZA TIME!,” “Bathers,” “Jew York,” “Hair Show,” and “Snail Salon”. They’re not the same, but they tend to share an uninhibited mood, freedom not to be confined by a feeling but to float around from one to the next. This also makes it inherently apolitical.

“Snail Salon”, for example, is all about ambiance. Curator Adrianne Rubenstein describes the premise of nail salon as “a photographic unreality, in a dream, in a fairytale, in a place where vision is free of emotion.” It’s filled with cool, facile painting which blends its color and marks like expert mixology: Heidi Jahnke’s beautiful, but Dana Schutzian, pastiche; Peyton Cosell Turner’s faux eyelash wallpaper; Elizabeth Jaeger’s ceramic hands used as the centerpiece of a working fishtank; a dash of Helen Frankenthaler and Jutta Koether. Most noticeably, the show transforms a small concrete box into a nail salon dreamspace. Between Barb Choit’s splashy Nagel poster and the economically electric neon paintings of Mira Dancy on the opposite wall, you can fully immerse in the fantasy with none of the illusion-breaking art questions. It’s like experiencing Claes Oldenburg’s pastry case for the frosting, the beauty of skill without labor.

It’s like nothing I’ve seen in the real world; for some, that’s the problem. Last year, artist Christopher Ho attributed this to “The Clinton Crew” generation, children of the nineties whose work reflects that easy decade. Ho sees the direct activism of the eighties and nineties—Suzanne Lacy, Barbara Kruger, David Wojnarowicz—being replaced by a formalist wave of the late 2000s—Joshua Abelow, Dana Frankfort, Roger White. Ho believes that the generation born of “liberal, educated parents and baby boomer wealth” make work defined by a bubble “between AIDS and 9/11.” The death of painting was meant to be the birth of a new art, which could be brought to bear on the real and terrifying problems of an imperfect world. Instead, formalism took over where politics disappeared.

This may not be a generational problem so much as knotty times, as Jerry Saltz put it. Political artists like Lacy and Wojnarowicz were emerging at a time when rents were cheap, jobs were plentiful, and there was room to define one’s career on a smaller budget and outside the gallery circuit, where formalism seems to thrive. Also likely (and also probably symptomatic of a bad economy) formalism’s thriving because the art world is full of formalists.

That’s fine; like jazz musicians or chefs, some artists didn’t choose art out of a political will. You can’t force a revolution on people who don’t want to have one.

But if art wants to bear a relationship to the world outside, eventually, this has to end. If it’s anything like art, it’s going to, and a few recent shows make me hope that it will.

Michael Assiff’s “Bali Ha’i”, for one, looks like it would fit in with the fantasy narrative of nearby “Snail Salon”; it’s like walking into a Nintendo-themed Happy Meal, with bright green plastic islands poured into tropical-patterned molds. But the further you go into Assiff’s fantasy, the more you’ll find sadness. His patterns are extinct species, whose death year is tallied by Monster energy claw marks. The title, and the overall motif, comes from a Las Vegas “tropical” golf course, a nod to what Assiff calls the “happy forest” narrative we enjoy when we consume. It’s still a little fun for paintings about mass extinction (the show comes with mango lassi and other edibles) but it’s still hard to leave without thinking about it.

It’s a fantasy that embraces the world, as awkward and ugly as it is. It made me think of another painter Darren Goins– his latest series of cool, shimmering exercise bars (“flexible sculptures“) look like they would fit a perfect world. But instead they’re made for New Yorkers. Goins constructed the models in collaboration with kids from the Boys and Girls Club of Astoria, then installed them under the 7 train in Queens, and hired three performers off the Internet to free-pose on them during rush hour. The result was weird. Three people in sweatsuits did some push-ups, hoisted legs in the air, swung around a pole with one arm. Goins’ use of the gym-theme felt less like a fantasy than an invitation to participate. Commuters didn’t seem to know what to do, except meditatively stand around and smoke cigarettes together. The goals seem similar to KnowMoreGames’ current transformation into an Air BnB, where a show is made only for the random guests who sleep in the gallery. By career standards, these works do everything wrong. That’s a good sign.

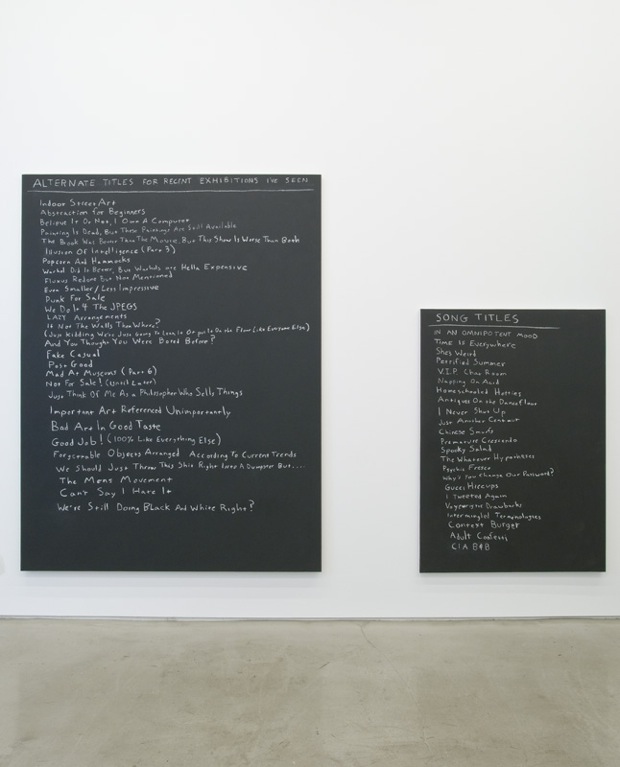

Scott Reeder’s

“Alternate Titles for Recent Exhibitions I’ve Seen”, from “People Call Me Scott” at Lisa Cooley

And nobody sums up the painting dilemma better than Scott Reeder’s list painting “Alternative Titles for Recent Exhibitions I’ve Seen at Lisa Cooley, like “Good Job! (100% Like Everything Else)” and “Painting Is Dead, But These Paintings Are Still Available”. Reeder could add his own art-world-eyeroll to his list of tropes (he’s been at this for a while). But rather than blaming money, per the norm, or art history, as he has in the past, Reeder blames the polite tedium on the complacence of his peers. It’s not nice, and I hope it stays.

{ 2 comments }

The art one encounters these days is a 77 Sunset Möbius Strip you can’t get off, so you stay on and on and then, exhausted you buy it, or frustrated you make an art work about it.

Vapid ephemera.

Comments on this entry are closed.