In the 1990s the New York transgender scene was pretty localized. Most drag queens lived within a 10-block radius of one another in the East Village, and nobody went further than midtown for a club. New York was still considered dangerous, but the city became decadent because of it; the police were so busy fighting street crime that the clubs were really wild and crazy. The club’s fostered this creative atmosphere that was energizing and attracted people who were marginalized elsewhere.

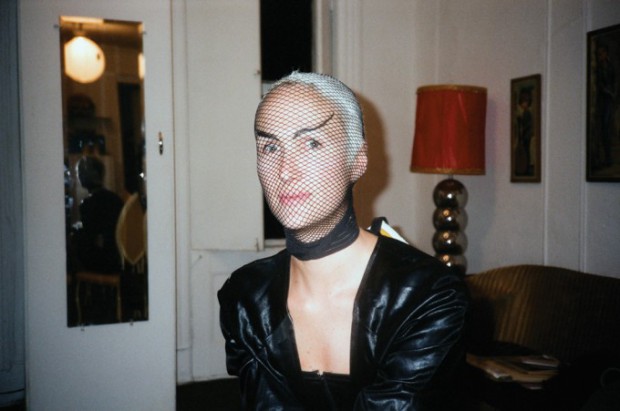

That’s how Linda Simpson, a well-known New York personality and drag queen remembers it. She currently has a show at ClampArt consisting of 11 intimate photographs taken of her friend and prominent village performer Page. Nestled in the hallway-shaped back room of the gallery, the images, taken with a 35 millimeter point-and-shoot at clubs or on the street, provide a good amount of insight into who Page was and why so many people cared about her.

“Page is one of those people, who even in New York, stands out as one in a million,” Simpson told me over the phone after the opening. “She really was a unique person.”

Page, a pre-op transexual who died in 2001, was described to me as someone who was both mysterious—frequently behind sunglasses—and wild. According to Simpson, she grew up in Vermont in a “comfortable manner,” giving her an almost country-club demeanor. She was shy and very conscious of her looks. At six-foot-tall, though, she didn’t have much to worry about. “She could have passed,” Simpson told me, adding, “Stealth is what we say in the trans community.”

Loyalty to her trans-friends kept her from integrating, though, and there was some benefit to that. “Back then drag alone was shocking to many people and transexualism was not understood. Page was a pioneer because she was very matter of fact about being transgender. Most of the people she hung out with were not—so she demystified it for them.”

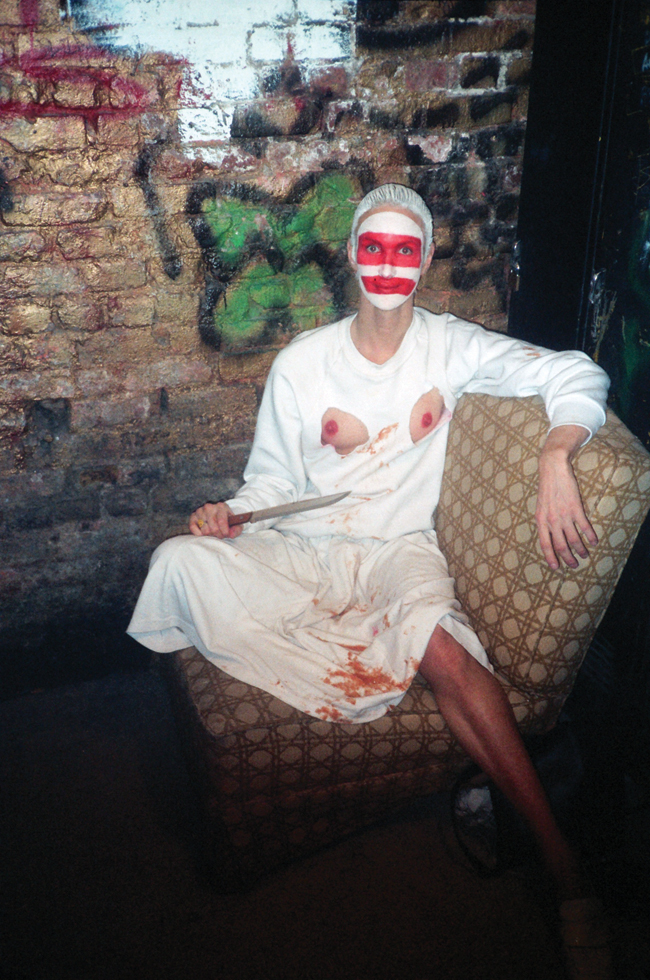

It’s hard to gauge how much influence one person can have on a community, but if Simpson’s images are any indication, it must have been a lot. Many of Page’s costumes documented in the show remain shocking today, and reveal Page’s interest in exploring trans-identity. In one particularly brutal photograph (pictured above), Page sits in a white coat covered in blood, with holes cut out around the breasts. The image was shot just after a performance Simpson organized at the Pyramid Club where she had hacked off her dildo on stage.

That performance, like many, stood in contrast to those of many other drag queens in those circles who mostly lip-synced popular songs. Page’s work resembled performance art. “We were not plugged into the art world,” Simpson made clear when I mentioned this ,though. “We might might have known a couple things, but this was performance for the sake of entertaining other people in clubs.”

I asked Simpson if the exhibition offered any closure on Page’s death, a question that proved tough to answer. “I don’t know. It’s difficult…” she began. “I know Page would have liked this. And if I can keep her freak flag flying high, then I will. But I don’t want it took like it’s some sordid obsession. I mean, really, Page is special.”

And as if to signify that, the fire alarm had to go off at the opening. The alarm rang for 20 minutes, then the fire department came. “I’m not religious or spiritual or any of that,” Simpson began, “but I just knew that Page was going to make her presence felt.”

Linda Simpson‘s book, “Linda Simpson: Pages” is available at the gallery for $20. It includes 30 color illustrations and an essay by Simpson. What follows is a slideshow from the opening with commentary by Simpson.

Linda Simpson, Pages, at ClampArt. All photos: Christian Grattan

Next to me is painter Scooter LaForge, and next to him is Gazelle, who champions cutting edge nightlife and fashion on his website, Freakchic.com. I don’t think he ever had the chance to meet Page, but she’s exactly the type of imaginative type of personality that Gazelle appreciates.

Paul Alexander is a member of the band The Ones and a fantastic nightlife photographer. Paul used to emcee at the nightclub Mother on West 14th Street, where Page sometimes performed.

Michael Formika Jones (a.k.a. Misstress Formika) came into my life about the same time as Page, when I was hosting drag shows at the Pyramid Club in the early 1990s.

Denise and I have known each other since the early 1990s when we worked at Interview Magazine. She was the production manager and I was a freelancer in the art department, back when you pasted-up magazines by hand.

Left is Mark, Scotty is right. I met them on the nightlife, which is where I probably met most of the people who attended. Throughout the 1980s and early ’90s, I lived for the after-dark scene.

Thomas Onorato used to one of nightlife’s ruling door people, and now owns his own public relations company

John is a fashion student. He was also one of the go-go dancers at my book release party for PAGES at the Cock, the gay dive bar on Second Avenue.

Wayne Northcross writes about art, culture and fashion for the New York Observer. Also, Wayne wrote an article about queer artists for My Comrade, the magazine I used to publish.

Comments on this entry are closed.