Inside Out: Curated by Ben Gocker

Interstate Projects

66 Knickerbocker Avenue

Bushwick

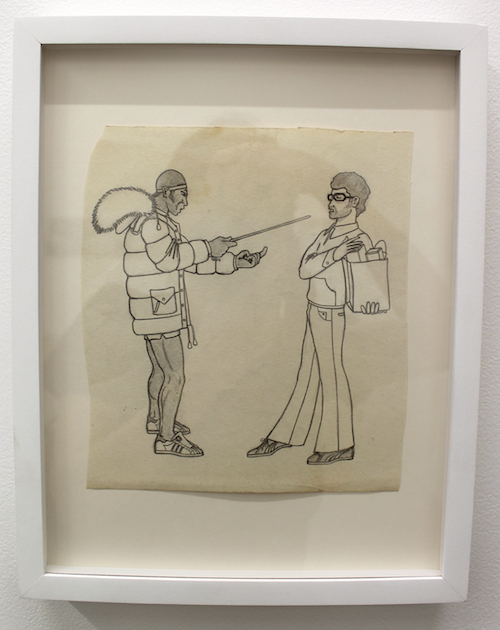

What’s on view: A two-person show: Paintings, records, and T-Shirts by former inmate Armand Schaubroeck, who’s now a bit of a mini-celebrity for sixties and seventies-folk-and-rock-inspired music, and ads for his store “House of Guitars” (T-shirts with the store’s logo are on sale in the gallery). Schaubroeck created this series of paintings after a three-year term in a maximum security prison, after he was convicted in the early sixties, as an 18-year-old, for theft.

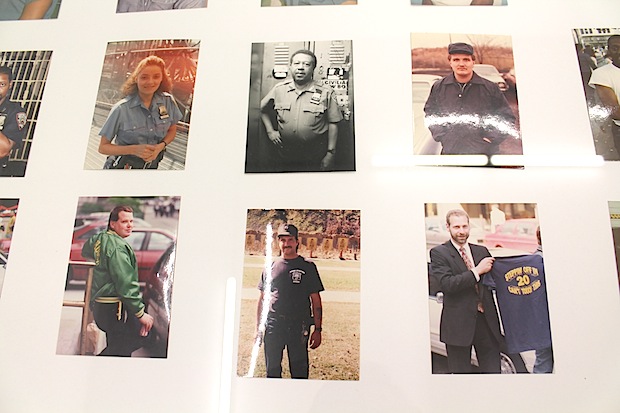

The other half of the show are photographs of prison staff and inmates, by longtime Rikers Island corrections officer and well-known street photographer Jamel Shabazz. Shabazz has included a shelf of books he read while working in prison, with titles like “Understanding and Changing Criminal Behavior”; “Black Robes, White Justice: Why Our Legal System Doesn’t Work for Blacks”; and autobiographies of Angela Davis and James Carr. Shabazz has also included children’s drawings of prison violence, which were prompted by his own descriptions of violence.

Andrew Wagner: Orange is the New Black this isn’t. Inside Out doesn’t try to gussy up prison life into an entertaining fantasy of what life’s like “on the inside;” it confronts the realities head-on, with voices from both sides of the system. Shaubroeck’s paintings portray both the emotional torment of being cut-off from the outside world (like a painting of Schaubroeck hanging himself, a breakup letter from his girlfriend attached to his hand) and the abuse suffered at the hands of prison guards. Shabazz’ grainy, black-and-white photographs, meanwhile, seem to give voice to an ambiguous unease with the system he works for. And a glass case full of small snapshots of Shabazz’ coworkers reminds us that prison guards, as ruthless as we often imagine them to be, are usually just people trying to do their jobs. There’s no TV villains or heroes in this show’s vision of prison life–only a deeply corrupted and flawed system that’s become “inside out,” or, as Ben Gocker in the press release writes, “not right…out of order, it isn’t how it ought to be.”

Whitney Kimball: No, not Orange is the New Black, but this wasn’t a black-and-white docudrama, either. The show’s filled with weird incongruencies, which all come from individual brushes with the prison system. It’s an unexpected subject for zany installation/collage artist, fiction writer, and first-time curator Ben Gocker, for example, who kind of stumbled on the subject when coming into contact with former inmates through his gig at the Brooklyn Public Library Bushwick branch, and he’d heard of Schaubroeck from watching his freaky “House of Guitars” commercials as a kid. I’m glad Gocker did take up the subject, because his unassuming sensibility lends itself to a humble presentation of individual experiences.

First, there’s Shabazz’s collection of smiling photos of prison guards, which you brought up– it’s like a high school yearbook, except some of them are holding their kids. Not to mention, the unlikelihood of the fact that a corrections officer would read Angela Davis by day, mentor kids by night, and photograph city life on his off days. Ben Gocker writes that Shabazz’s prisoners were often also his neighbors: “It wasn’t uncommon for him to see someone he’d photographed a week before show up at Rikers or, vice-versa, reconnect with a former inmate on the outside.”

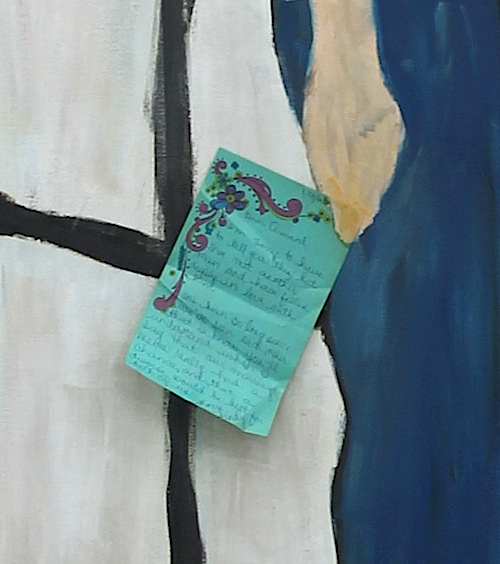

And then there’s Schaubroeck’s black humor, which weaves throughout the horrible situations his paintings depict– like a prisoner with his pants down lying face down on the floor with blood dripping down from his anus. According to Tom Weinrich, Schaubroeck had hoped to spray that flowery break-up note in “Cut My Friend Down” with perfume for the show, but nobody had any onhand at the gallery.

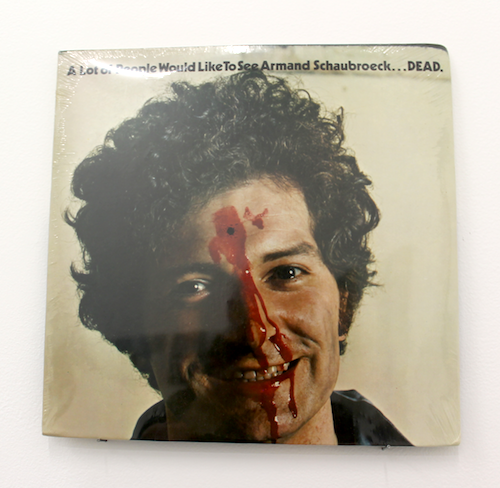

Gocker notes that these paintings had been in storage for 30 years. After his release, Schaubroeck made a 1972 run for New York state senate, on the platform of prison reform. He also clearly found ways to capitalize on the experience. One record cover titled “A Lot of People Would Like to See Armand Schaubreock…DEAD” features a smiling self-portrait with a bullet in his forehead. He became kind of an underground persona; Vincent Gallo is supposedly a fan.

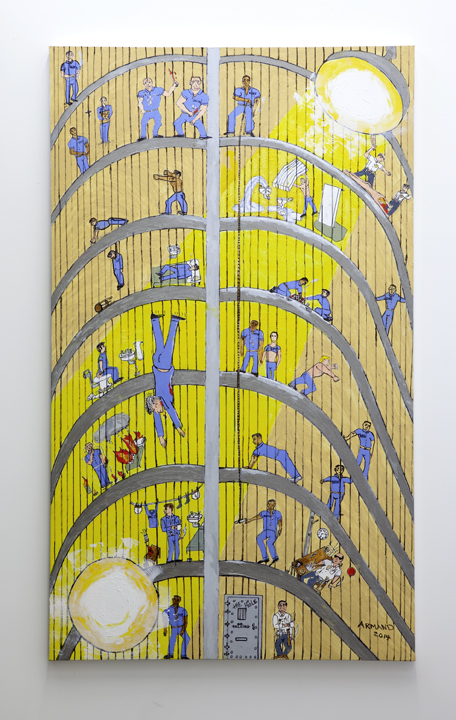

And unlike Orange is the New Black, the show never lets you never forget that this is prison. By the doorway hangs the most recent work, a jarring vertical yellow cartoon tableau, which Schaubroeck painted just for the show. Weinrich reports that Schaubroeck’s cell was in a tower, which influenced the strange ribcage-like layout of cells. These are all situations which Schaubroeck witnessed: a man plummeting headfirst down the atrium; a man setting his bed on fire; guards beating a bloodied naked man; a man hanging; two men holding hands; passing notes from cell to cell on a long rope; a man clutching a Bible, who hoped to use newfound religion as his ticket to freedom. It’s hard to look directly at the characters because Schaubroeck painted spotlights pointing right at the viewer. But fifty years after his release, the memories loom large.

I recommend this. The show closes August 3rd.

Comments on this entry are closed.