If “Best Man Holiday” gave you the impression that mainstream culture is finally diversifying, hold your applause. A new study from USC’s Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism took a look at the number of underrepresented minorities in films, and its findings are grim. Last year, an NPR story reported that eleven films in 2013 were both made by black directors and starred black actors; the article’s author, Hansi Lo Wang, suggested this was a sign of progress in an industry that’s been frequently criticized for its racial inequalities. But as the Annenberg School’s study shows, change has yet to come, and Hollywood is just as lacking in diversity as it has been for the past several years.

If “Best Man Holiday” gave you the impression that mainstream culture is finally diversifying, hold your applause. A new study from USC’s Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism took a look at the number of underrepresented minorities in films, and its findings are grim. Last year, an NPR story reported that eleven films in 2013 were both made by black directors and starred black actors; the article’s author, Hansi Lo Wang, suggested this was a sign of progress in an industry that’s been frequently criticized for its racial inequalities. But as the Annenberg School’s study shows, change has yet to come, and Hollywood is just as lacking in diversity as it has been for the past several years.

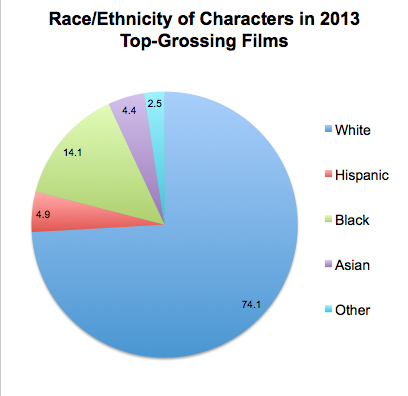

The numbers are pretty troubling across the board. For actors, if you’re not white, you’re going to have a hard time finding a job:

- In 2013, only 25.9% of film characters were not white, even though even though 36.3% of the entire population identifies as either not white and/or as Latino.

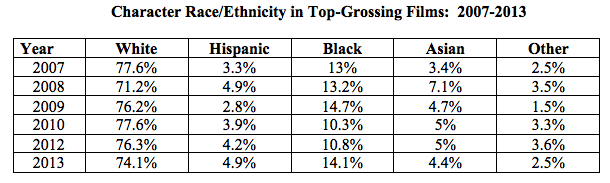

As a chart included in the study shows, these percentages have stayed pretty steady since 2007:

The representation of Latinos on-screen is especially skewed:

- While 16.3% of the population identifies as Hispanic, they only made up 4.9% of film characters

- Hispanic characters, both male and female, were the most likely group to be hypersexualized on screen. Hispanic women were shown in sexualized attire 36.1% of the time, while Hispanic men were shown in sexualized attire 16.5% of the time.

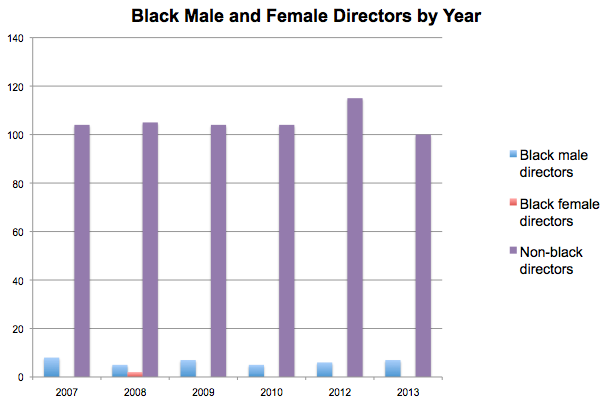

As for the notion that black directors are becoming more prevalent, the study concludes just the opposite:

- The number of black male directors per year stayed pretty stable at about 6% of directors per year. As the study writes, “there has been no meaningful change in the percentage or number of Black directors across the 6 years.”

The numbers were far more unsettling for black female directors:

- Of the 672 film directors the study considered, a mere two were black women, or 0.3%. Those two directors both made films in 2008. In 2009, 2010, 2012 and 2013, no top-grossing films were directed by black women.

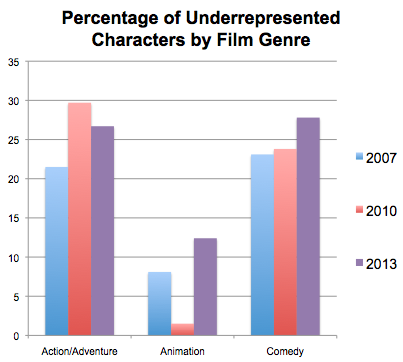

The study also took a look at percentages of underrepresented minorities across genres, finding animation to be the most lacking in representation:

- For 2007, 2010, and 2013, the percentage of underrepresented characters in animated movies remained below 13%.

- 2010 was particularly bad for animated movies, with only 1.5% underrepresented characters.

Considering that in the U.S., nearly half of children under the age of 5 are not white, these statistics seem particularly bad. While 2009’s The Princess and the Frog’s Tiana might have seemed like progress as the first black Disney princess, she’s since been outnumbered by other films with white female protagonists like 2010’s Tangled, 2012’s Brave, and 2013’s Frozen.

These statistics are a reminder that diversity remains a pressing issue across our cultural industries. Indeed, the art world isn’t too much better:

- A study recently released by BFAMFAPhd showed that 74% of New York City’s artists are white.

- This year’s Whitney Biennial only included 7.6% black artists (that percentage does not include Donelle Woolford).

Last year, some claimed that we’d suddenly entered the African-American film renaissance. Of course, there were milestones last year worth celebrating–Steve McQueen being the first black director to make a film that received an Oscar for Best Picture, for one. But a single film does not make for a cultural shift. We’ve seen this before in the art world: Roberta Smith called the 1993 Whitney Biennial a watershed moment for its heightened focus on politics and its greatly increased diversity. But that Biennial has hardly led to lasting structural changes, and Smith seemingly was too soon in her assertion. Similarly, it seems like it might have been too soon to declare an African-American film renaissance. Which is a shame, because with the U.S. growing more and more diverse, our cultural institutions, whether Hollywood or museums, are at risk of becoming totally irrelevant.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Steve McQueen was the first black director to receive an Oscar for Best Director. Instead, Steve McQueen was the first black director to make a film that received an Oscar for Best Picture. The post has been updated accordingly.

{ 1 comment }

Slight correction: McQueen didn’t win Director, he was the first black director to have a movie win Best Picture.

Comments on this entry are closed.