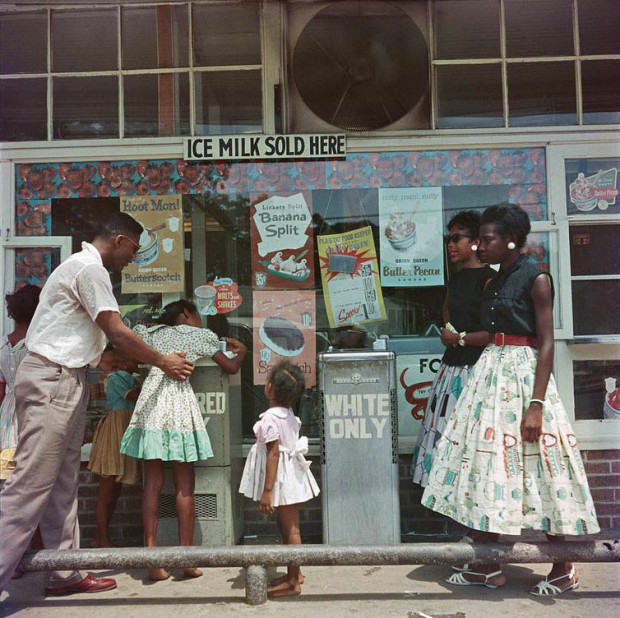

“At Segregated Drinking Fountain,” Mobile, Alabama, 1956. Gordon Parks (Image courtesy of the High Museum)

“Hard to believe,” the woman next to me remarked thoughtfully in “Segregation Story,” a photographic exhibition of Jim Crow-era Alabama at Atlanta’s High Museum. I’d thought the same thing several times of photos of families lining up behind “Coloreds” signs, and cold looks on white faces. How could America let this happen? But when you compare the show to the 2014 news cycle—as I write this, Ferguson awaits the verdict on Michael Brown’s shooting—images of deep south segregation only make clear how little things have changed.

Shot by African American photographer Gordon Parks for a well-known 1956 Life Magazine image essay “The Restraints: Open and Hidden,” the High Museum provides an uncut version with over 40 photos. The timely exhibition itself is just a sampling sourced from over two hundred color transparencies recently re-discovered by the Gordon Parks Foundation.

The selections here mostly follow three generations of the Thornton, Causey, and Tanner families navigating a world where the houses are shabby and small, and the department stores are spotless and intimidating. Overall, it paints a simple picture of what was: children on the outside looking in; colored water fountains and entrances; crowded beds in Alabama shacks. Some photographs fall on the Rockwell spectrum, with almost too-perfect compositions in colorful pastel palettes. Barefoot children crowd expectantly around an ice cream parlor’s “COLORED” water fountain and side entrance; a young mother and daughter look off into the distance, under of a neon “COLORED ENTRANCE” sign; a father looks exhausted in front of a “COLORED” sign on a train platform. If permanently engraved on the cultural psyche, though, the familiarity of these characters, their expressions, and their settings drives home the fact that this was a fairly mundane sight in the fifties.

It’s the more casual photos, though, that really take you by surprise. One over-the-shoulder shot captures a sour white mother sitting a seat apart from her exasperated black nursemaid, in an airline waiting terminal. Half the image is cropped by a blurry head, apparently used to hide the camera; the viewer’s left to imagine the potential stakes of shooting that photo. In another print, a black child looks back at the camera from a doorway. He’s wearing a red cowboy hat, a simple reminder that there were no black cowboy movie stars.

For those of us unfamiliar with unequivocal hatred as part of daily life, it’s easy to believe in the progress narrative that Martin Luther King’s dream reversed history leading to an upward ladder through The Jeffersons to a black President. (To show how far 1950s segregation pictures are considered from today’s politics, the show is sponsored by Coca-Cola, a company with a well-known history of racist advertising).

“Ondria Tanner and Her Grandmother Window-shopping,” Mobile, Alabama, 1956. Gordon Parks (Image courtesy of the High Museum)

Why is an image of “colored” water fountains of yesteryear compartmentalized from those of today’s black-filled prisons? Or even an image of a dozen police pointing guns at an unarmed man? Without the 1950s dresses and ice cream parlors, several of these photos could be contemporary; in Ondria Tanner and Her Grandmother Window-shopping, we look down from a department store platform at a little black girl, stopped in her tracks and staring up at a group of chalky white mannequins. The simple illustration of racial imbalance looks like a relic of the bygone days of golliwogs; now, pop culture now walks a thinner line between appropriation aesthetics (Miley Cyrus and Iggy Azalea), and a general whitening of black divas (blonde Beyoncé, and a lightened Nina Simone, resurrected in the form of Zoe Saldana). What’s okay to do with race is more of a fuzzy grey area.

The show ends with a reminder of what’s not in frame, events that were too dangerous to document. The text quotes an entry in Parks’s diary: “My thoughts swirl around the tragedies that brought me here. Just a few miles down the road, Klansmen are burning and shooting blacks and bombing their churches. …Lying here in the dark, hunted, I feel death crawling the dusty roads.” His subjects suffered consequences, too. After the images were published, the young mother Allie Lee Causey—a vocal proponent of integration—was fired from her teaching job, and gas stations refused to serve her husband. As the New York Times reports, the family left the state two weeks after the essay was published, and Life eventually paid the family $25,000 to help them start over. (It’s hard to imagine a site like BuzzFeed giving that kind of support to one of its subjects today).

With less optimism about class mobility, and a seriously-shaken dream of racial equality in U.S.A., this series is well worth reconsidering. Are we so progressive? For answers, and more on “Segregation Story,” look to the news.

Comments on this entry are closed.