What do you get when you apply the pastoral idealism of the early 20th century illustration to the ugly post-atomic consumerist reality of the last four decades? You’ll find the answer at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, where the first retrospective of Jamie Wyeth combines Renaissance drawing techniques, druggy seventies icons, personal backstory, and idealized New England seasides– all adding up to a jumbly, at times incoherent, show.

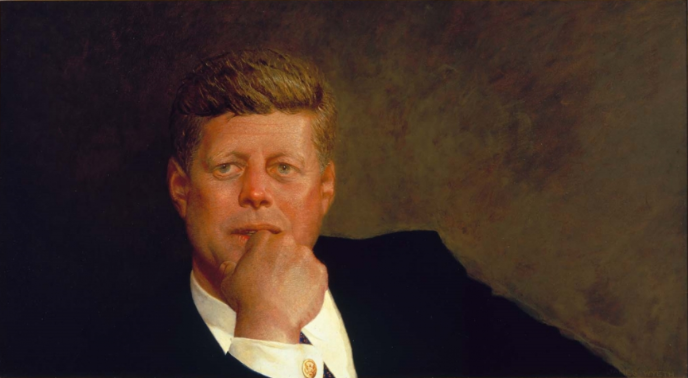

The son of realist painter Andrew Wyeth, and grandson of famed illustrator N.C. Wyeth, Jamie inherited art world prestige. As evidence, the show opens with a posthumous portrait of President Kennedy, which Wyeth completed at age twenty-one, four years after the assassination. The portrait establishes Wyeth’s ability to explore his subject intensively; a highly-detailed Kennedy is depicted lost in thought in the middle of the Cuban Missile Crisis. One eye wanders to the left, and the tight, rectangular canvas cramps his head and shoulders. According to the wall text, Kennedy’s brother Ted thought it was too lifelike. Like most Presidential portraits, this is still not a particularly compelling portrayal (he still looks like another guy in a suit), but it’s obviously been mulled-over.

From here, the rest of the show is a crapshoot. Rooms are roughly arranged by themes Wyeth returned to throughout his life, often with thirty-year gaps between them: 1970s New York, seasides, barnyards, portraits of his wife and his young male muse, and a room filled entirely with seagulls. Early in the seventies, Wyeth got looser and sketchier, with a few moments of detail sprinkling inconsistent focus and generally idiosyncratic decision-making.

For starters, why all the cardboard? Wyeth often chooses the material as his canvas, such as a few portraits of Andy Warhol, who was attracted by Wyeth’s good looks and fame. This resulted in a portrait exchange; Warhol made a silkscreen of Wyeth looking like a moviestar, and Wyeth made a few boilerplate sketches and one finished painting. The first, a 1976 study of Warhol’s feet (a tribute to Warhol’s plan to make portraits of celebrity feet), is a wholly unremarkable study of feet, although the casual 20-minute-sketch suggests the closeness of the relationship. Then there’s the surprisingly wholesome “A.W. Working on His Piss Series,” painted in 2007. The loose portrait depicts Warhol reflective, and cradling his Dachshund Archie under his left arm—not the first pose that comes to mind when you think about Warhol and his assistants pissing all over copper pigment. No splashback made in onto the Wyeth.

But in another rare stroke of clarity, a polished 1976 Warhol portrait will stop you in your tracks. Here Warhol– depicted in oil paint worked up to an almost jewel-like surface– appears both as though he’s staring down the barrel of a gun and laid out on a morgue slab; Archie stares menacingly and rodent-like from the right-hand corner of the canvas. It fabulous. “I see this portrait of Andy as a sort of portrait of New York,” Wyeth is quoted in the wall text. To Wyeth, New York is clearly a life-sucking hole.

Glimpses of such precise vision perhaps explain curatorial interest, but a multitude of head-scratching decisions that follow make you wonder why we need the full career survey. More sketches of feet, side profiles, and board room portraits offer sameness throughout the entire show.

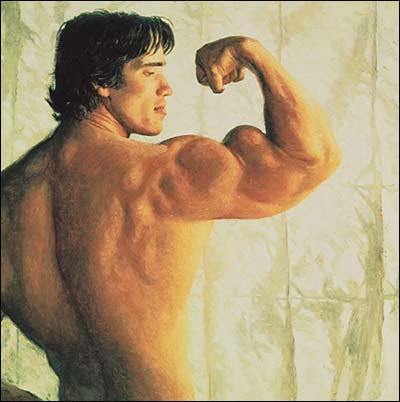

Fortunately Wyeth randomly takes sharp turns into bizarroland (debatably intentional). Take the recent tableux vivants recreating memories of 1970s New York. At first glance, they’re fashionable bohemia; up close, they’re more like “Rocky Horror Picture Show”. The Factory dining room looks like a heritage antique dollhouse, except for the fact that it’s populated by Warhol and well-dressed friends gathered around a dining table watching rough cuts of “BAD.” Then there’s a recreation of the fancy restaurant La Cote Basque, featuring a Dr. Frankenstein version of Truman Capote, with little black sunglasses stuck on his pasty globular face. Similarly incongruous: nearby, a finished 1977 portrait shows Arnold Schwarzenegger flexing. “It looks like bread!” one kid shouted. It was an accurate assessment of the doughy biceps. Add to this, Schwarzenneger appears to be flexing in front of a soft white curtain. While I personally take pleasure in a soft, bready version of, by that time, seven-time Mr. Universe, it’s neither here nor here; the standard macho flex pose mostly provides another straightforward muscleman image.

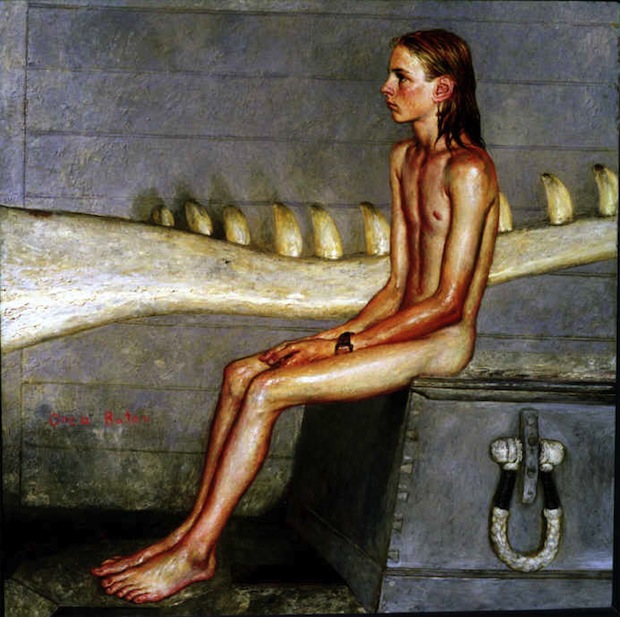

Another strange decision: acrid yellow backgrounds. Wall text explains that the hue references Wyeth’s grandfather’s use of yellow backdrops in his end cover illustrations for “Treasure Island.” But blaring pure cadmiums overpower his subjects– especially his muses, ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev and teenage boy Orca Bates.

Orca, a lean, serious boy with shoulder length blonde hair– often nude but tastefully covered– bears an immediate resemblance to the exotic, sturdy beauty of his father’s famed muse Helga. We learn from wall text that Orca was a native of Manana Island, off the coast of Maine. These are the largest and most obsessively focused paintings in the show, but the Helga Paintings cast a long shadow; missing is the sense that Wyeth lived and breathed his subject. A beautiful and attentive 1990 painting “Orca Bates”, for instance, creates an almost translucent glassy surface in the skin, but the tenderness is lost on a dispassionate side profile view.

What follows are more paintings of Maine life: realistic flowers, old bell towers, pictures of bird, chickens, more hay. A handful of high points here include soft-lit, reverant portraits of his wife; portraits of Orca; a sheep looking out protectively at the sea. Blander, but detailed, landscapes are often framed as brooding and metaphorical; usually, this outsizes their significance. “Bale” is a straightforward painting of hay. “Raven” is a picture of a raven. “Pumpkinhead” is a self-portrait of the artist wearing a pumpkin on his head. Not much to say here.

New England landscapes lead to a room of vicious raptor-like seagulls; at best, one image provides a consistency of detail making a gull melt into a field of seashells. At worst, we get rough acrylic-on-cardboard paintings like “Inferno,” of gulls tearing each other apart in front of a flaming furnace. Again, this seems like a strange judgement call, as the show’s fiercest composition has to compete with ribs in the cardboard.

A nearby Bob Ross-style artist-at-work video only adds more mist. Further mythologizing the artistic process, the title of a cardboard painting “Inferno” appears with a dictionary definition of the word “inferno”; title shot then fades into a shot of the island, which cuts to the artist’s studio. Cardboard “creates another world for me,” Wyeth explains. A close-up shows the artist painting a semitransparent gull’s eye, remarking that “when that gull comes to life…that’s why you paint.” As unfair as it is to expect an artist to fill his father’s shoes, all the same, I miss Helga.

Comments on this entry are closed.