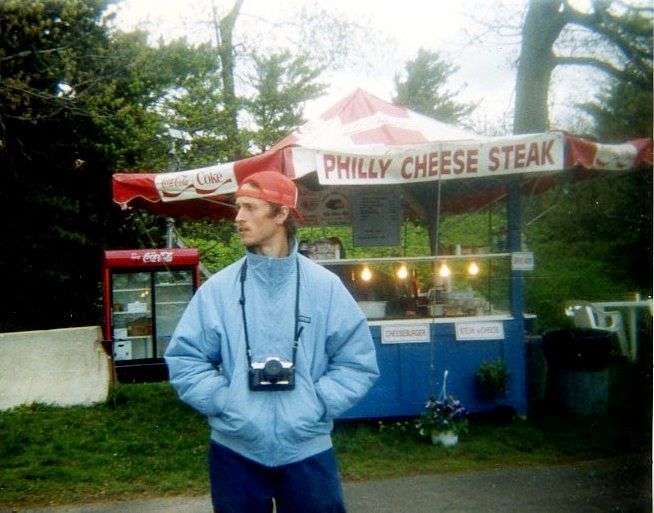

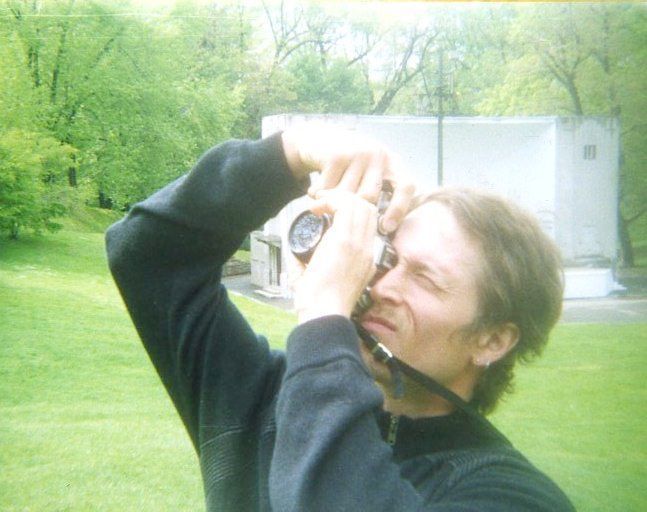

In 2002, I moved back home to my parents’ house in Brighton, a suburb of Rochester, New York, and began working first at a call center then at a sheet metal factory on Hollenbeck Street in the city proper. I got the sheet metal job through a friend of mine whose father knew someone at the plant and could set the both of us up with more or less regular work stamping out the implacable parts needed for the likes of Cisco, Xerox, and – less and less, it seemed – Kodak. My grandfather had been a Kodak engineer during that little camera-&-chemical outfit’s apogee, and when he died in 1999, he left behind a number of cameras. Some of which, as luck would have it (or, as I would have them) were sentimentally small enough to sift through the sieve of aunts and siblings all the way down to me. Setting aside the doomed child of my grandfather’s engineering career, the Disc camera, I gravitated toward a cheap and slim silver thing that could be packed with large black licorice-like rolls of film – a 110. I loved it because it was cheap, on the threshold of its obsolescence, and, most importantly, perhaps, easy to load and zombie-efficient when it came to my preferred mode of photo-documentation: snap-shooting.

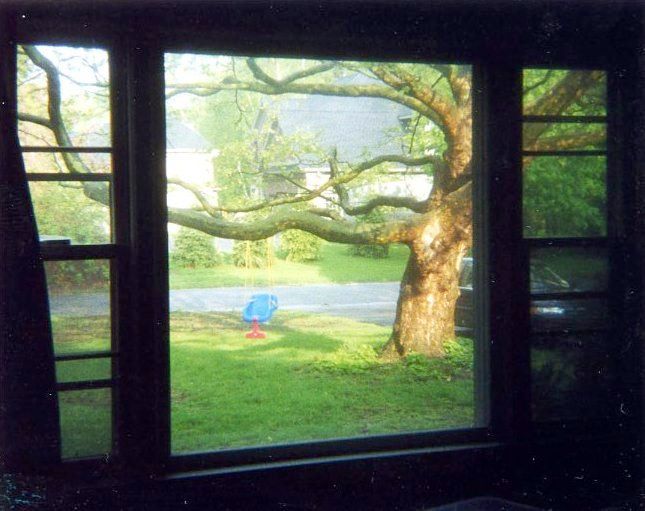

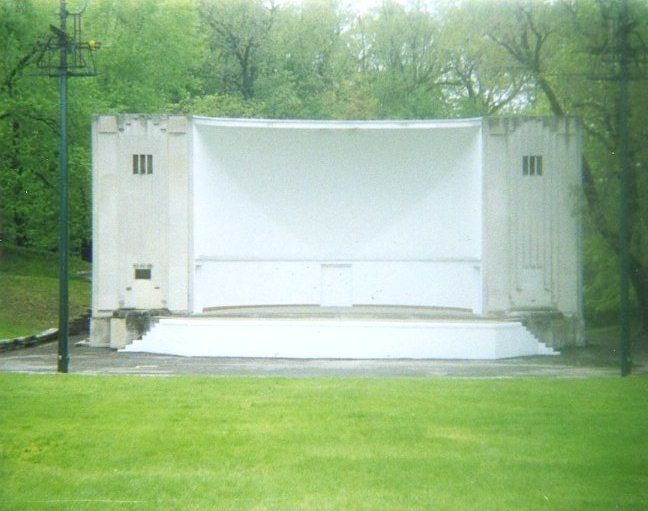

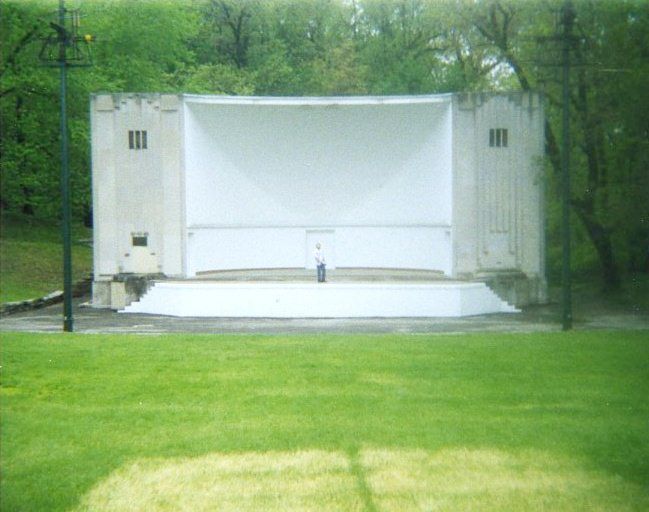

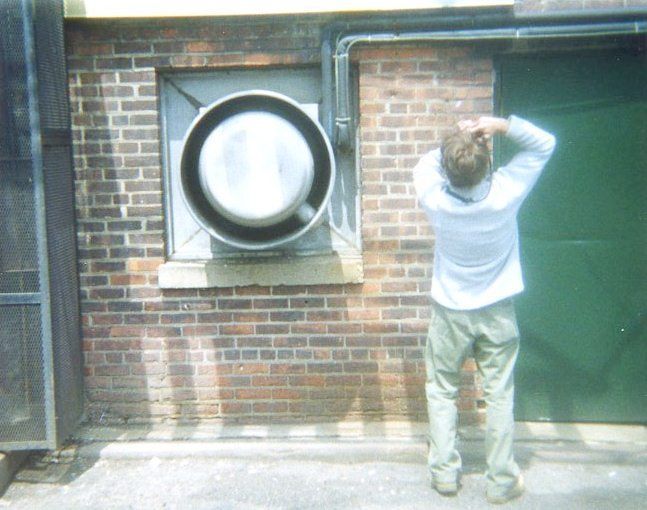

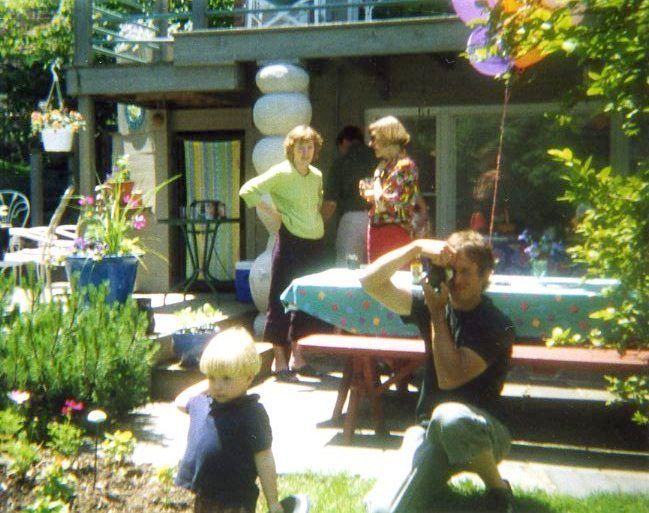

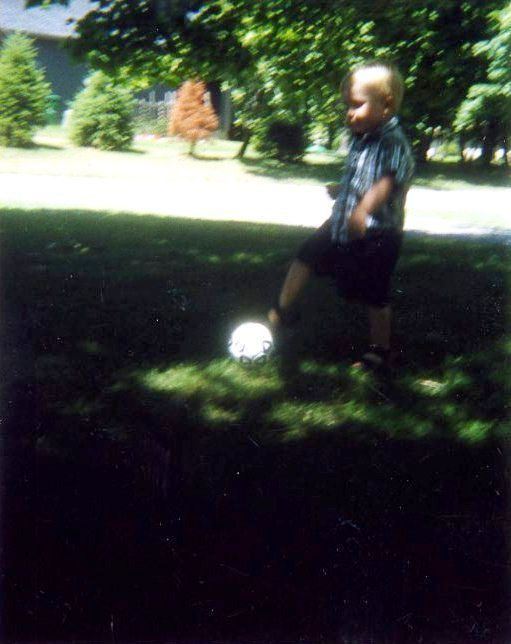

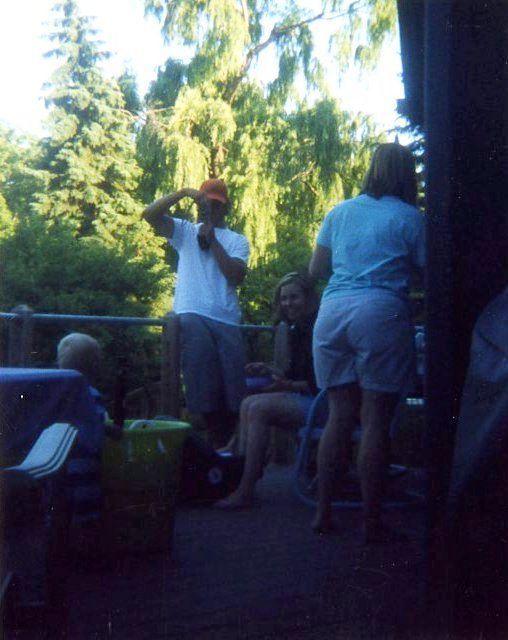

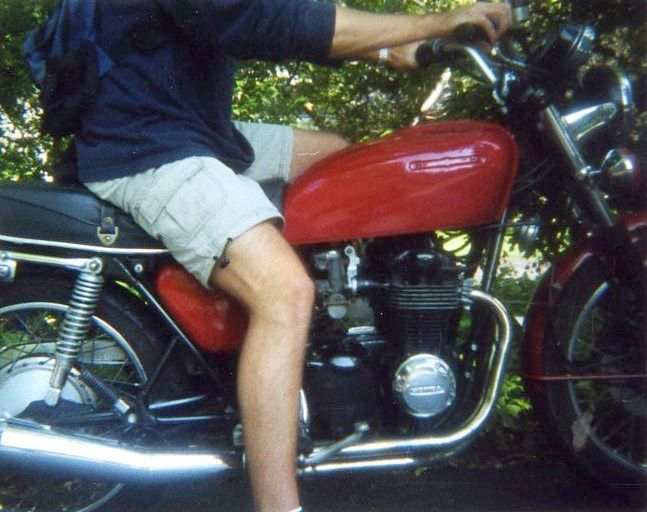

But I wasn’t alone in 2002. My brother also moved home, leaving Toronto and a graduate program he didn’t much like. At first he got a job at the call center with me, and we quizzed strangers nightly about celebrity bangs, household cleaners, and the policies of George W. Bush. Later, he got a job building decks in all the new suburban developments, applying BBQ poultices to the chancres of invaded old farm lands. It was a pretty depressing year. Neither of us really knew what we wanted to do. We shared a bedroom. We stewed. We visited ghosts. We got those old cameras out and drove our Bonneville around town taking photos. Sometimes our dad would come with us. Sometimes, apparently, I dressed in all yellow; it must have been my power color that year.

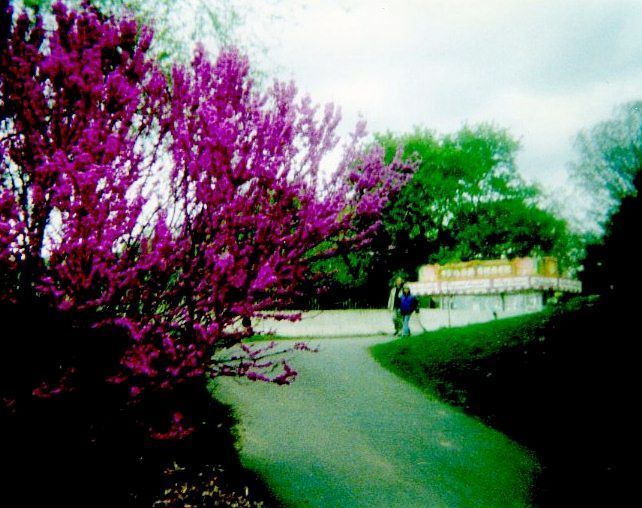

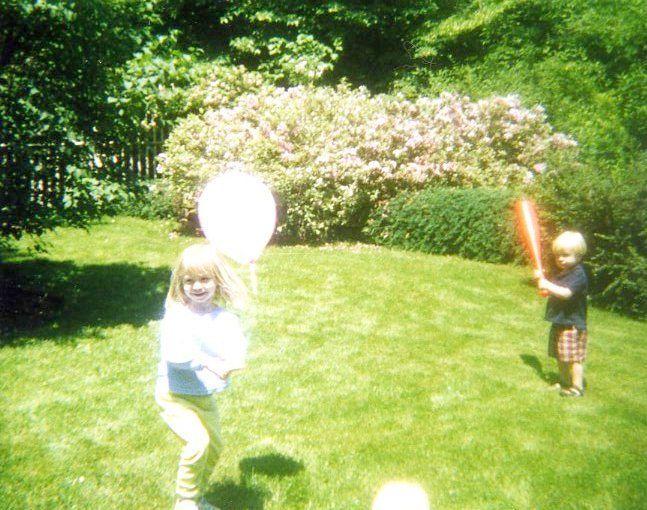

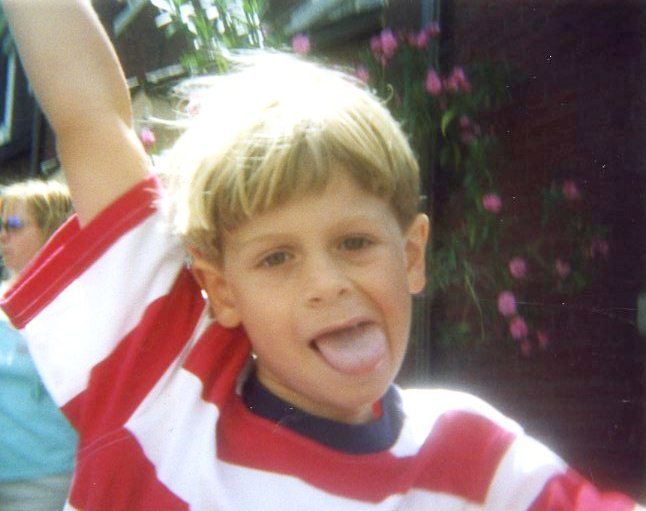

For reasons beyond my understanding, the camera I used – the 110– took some really lovely, sun-grained, light-glutted images. Even the shadows looked all thick and roughed with light. And of course I could figure out the technical process behind the effects – it’s a mechanical process, not magic – but I prefer to let its operation persist in mystery. Whatever it was, the camera had a transforming knack: willow trees shaking with light looking like lemon-lime shaved ice; bluebells vivid as eyeshadow; a person in a white sweatsuit glowing like cut coconut; a child’s orange plastic bat spectral as neon in rain. And Rochester’s indefensibly overcast sky looking as crummy and heart-rendingly oppressive as it really is. It’s all there. And for a few years after I took these photos they felt really unique and, well, magical.

Then everything that has been happening to us began happening. The cruelly ironic product of its short sighted business model, Kodak’s “cheap-camera/good-film” aesthetic – from Instamatics to these 110s – was imitated and outstripped by Instagram and what ever other digital formats were (and are) out there.

What follows are scans of 60 or so photographs I keep in albums and yellow Kodak envelopes in my apartment. Attend to them as you might the sometimes dull details of a stranger’s dream narrative; not too closely, perhaps, but sensitive to the sympathies that inhere.

{ 1 comment }

so boring… in a bad way

Comments on this entry are closed.