[Ed note: “Two Experts On…” is a new periodic interview series in which we’ve asked a maven in a creative field to talk shop, in nerdy detail, with a fellow specialist.

This week, courtroom illustrators Elizabeth Williams and Aggie Kenny discuss decades of witnessing high profile cases up close.

Williams’s work has appeared on the cover of major news publications including the New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and USA Today. Kenny won an Emmy for her work on the Mitchell-Stans trial for CBS, and is especially known for her coverage of 9/11 first responders and long-term coverage of the US Supreme Court.

Both of their work is featured in the new book The Illustrated Courtroom: 50 Years of Court Art, along with writings about their cases and their subjects over the years. [All images from The Illustrated Courtroom.]

Elizabeth Williams: What do you think, Aggie, is the most important aspect of your training that you use in a courtroom?

Aggie Kenny: Well, as in live figure drawing, it’s important to acclimate yourself to one-minute sketches. Because that’s essentially what courtroom drawing is all about. People are in constant motion. How do you feel, Liz?

Williams: Absolutely. The second very important attribute of creating courtroom art is a fast technique that can read dynamically on a television screen, when it’s up for five seconds, that can read well if it’s reduced down to a postage stamp size. It can’t be something that is that delicate, because it simply won’t read, it won’t communicate the scene. Courtroom art is about communicating, and communicating it very quickly.

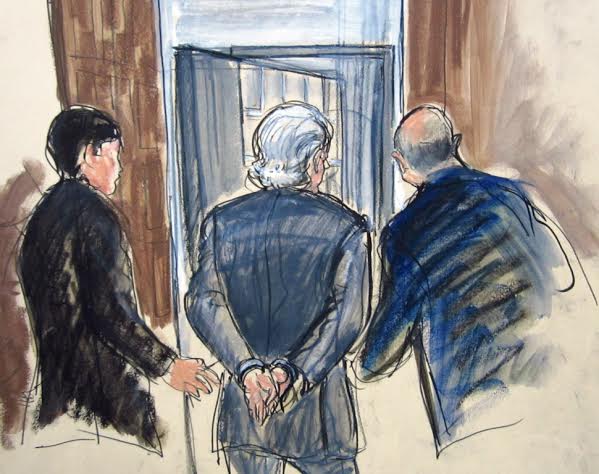

Kenny: And I think you really excel at being able to know what’s going on, to draw it incredibly quickly. For example, I believe you are the only artist at the Madoff trial who actually got a Bernie Madoff being put in handcuffs and being sent to jail.

Williams: That’s another important part of courtroom drawing that’s not so much about being an artist, it’s more about being a journalist. I don’t think I know any courtroom artist who’s taken a class in journalism; you just have to anticipate what the story’s going to be, and you need to develop a news sense.

Back in the day, we used to have the reporter or producer right next to us. We don’t have that anymore. We’re on our own. And that was the thing with the handcuffs. I knew that they’d been trying to get Bernie’s bail revoked, and the prosecutors couldn’t get it done. Madoff pled, and the marshalls finally put those handcuffs on him, and they walked him into the jail cell, from the courtroom, I knew that was what everybody wanted to see. It wasn’t a great drawing or anything, it was more like a great moment. In that regard, as an artist, you can’t be so concerned with the artwork, you just gotta get it down. And that’s the other thing, sometimes we send out stuff that we’re not so crazy about sending out–

Kenny: We’ve all been there.

Williams: So what do you think is more important? Is it the journalistic side, or the artistic side?

Kenny: Well, I would lean towards the journalistic, because if you don’t get the right subject at hand, you might as well be out in plein air drawing a pasture or something.

Williams: Yes- there’s currently a courtroom art show in the Manhattan federal courthouse at 40 Centre Street, with some of Aggie’s work in it. And one of the things Aggie is always very good at doing is captioning her work and identifying who the people in the pictures are, which I am not so good at. In the archival dig of her studio, we happened to find a drawing of Mark Felt, whom we know now as Deep Throat. He was testifying in the Watergate-related Mitchell–Stans trial. And that drawing, he must have been off and on the stand pretty quickly, because all you could do was kind of get him. When you look at it, it looks like Mark Felt– but if she hadn’t written “Mark Felt” on that piece of paper, we wouldn’t have known who it was. They’re nice pictures, but what makes them really important pictures is the background.

Kenny: Well, I think the Mark Felt drawing also brings up another challenge, and that is– when there are often myriads of witnesses, you have to try to figure out who’s important and who isn’t. In this case, I certainly didn’t know how important Mark Felt was.

Williams: No one did [Laughs]

Kenny: And I happened to have drawn him. Perhaps on another day I would think it’s a minor witness and might not have drawn him. So it’s a challenge.

Williams: Well, something must have attracted you to him– he has a red tie and a red pocket square. I thought that was so interesting that you chose to make that visual note about how he kind of…it struck me that he wanted to be noticed. Not many witnesses get on the stand with a matching pocket square and tie and bright red, the well-coiffed hair– now they’re sort of clues to who he was, this person who wanted to be in the spotlight but was still clandestine and not yet known…and then finally exposed himself several years ago.

Kenny: Well, do we want to list the challenges we encounter on a daily basis?

Williams: Okay! You go first.

Kenny: Well, we were in court today, and I would say for us, lighting issues, distance issues– it’s often very hard to see the judge, to see the defendant. We often have to use binoculars to get any semblance of a likeness.

Williams: Exactly. A reporter can get notes from somebody else, but an illustrator can’t just look at somebody else’s drawing and make it up. You have to be able to see…lawyers can sit in front of their clients…I’d just drawn this Russian spy, and this guy did not want to be drawn, you could tell. He kept turning his shoulder around so you can only see his partial face. The speed at which you have to work, the deadline– the list can go on. So getting there early is key, because you need to get a good seat. You try to reduce the number of variables, and seating is one of them.

Kenny: And even when you’ve gotten there, and you’ve gotten a really good seat, things can happen– for example, in the Macy’s/JCPenny trial concerning Martha Stewart, an attorney– I believe it was for Macy’s– at one point complained to the judge that he was allergic to my watercolor. And therefore wanted me removed to the back of the courtroom, which he, in effect, did.

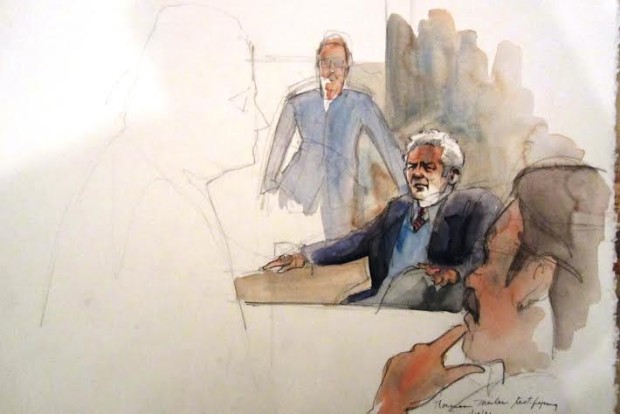

Williams: I remember that. In The Illustrated Courtroom, you talk about Norman Mailer taking your seat. Removing you from the Jack Abbott trial…

Kenny: Ruined my day.

Williams: But you still did a beautiful painting of Norman Mailer.

Kenny: I’ll never forgive him.

Williams: Sometimes you cover a hearing or an arraignment, and you really nail it, you really got the person down– and there are other times when you send stuff out and you’re like Oh, God. And there’s simply no time to redo it. You can’t hit the reset button. They’re not going to bring that defendant out again. Whatever you’ve got, you’ve gotta make the best of it.

What’s the most interesting case you’ve worked on, ever? The top three?

Kenny: Well…one of the most exciting was working for ABC, being sent down to Guyana for a hearing for Larry Layton of the Jonestown Massacre. It was quite amazing. And again, very challenging because when we finally got to the courthouse in the middle of the jungle, the judge informed me that no drawing was allowed in the courtroom. So things had to be done by memory, and that’s never fun.

Williams: You also had that experience with the Gainesville Eight.

Kenny: That’s right.

Williams: Which you made case law.

Kenny: CBS won that suit because the judge disallowed me not only from drawing in the courtroom, but from drawing from memory. CBS won that hands-down. [Ed note: CBS won a historic First Amendment lawsuit after Judge Winston Eugene Arnow ordered Kenny not to draw in the courtroom or from memory in the 1973 Gainesville Eight trial; see United States v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc.: Courtroom Sketching and the Right to Fair Trial].

Williams: I think the judge was removed. I think that’s actually mentioned on the courtroom sketch wikipedia page of that case. That was kind of when a courtroom artist made news and case law at the same time. So you’ve got one and two. What’s number three?

Kenny: Well, I would say the Iran-Contra case. For one, in that era, I had the luxury of covering the entire trial, which does not happen anymore. News agencies are interested in the bottom line– as [you] would say, they often parachute us in. But during the Iran-Contra trial, we really had the opportunity to not only have decent seats, but to really get to know the characters involved– it’s very important for artists to spend some time studying faces and poses and mannerisms. It really makes your work flow, as the days and weeks go on. We no longer have that opportunity.

Williams: But also, you covered James Earl Ray, the assassin of Martin Luther King. And that, you weren’t in very long. You did an extraordinary pastel drawing of him that’s in the book. It’s an absolutely gorgeous drawing of an absolutely twisted, horrible person. It’s very incongruous, because, as courtroom artists, you can do a lot of very nice pictures of a lot of very not-nice people.

That must have been a memorable case, I’d think.

Kenny: Again, it was quite a few years ago, so I can’t be too specific about it. But I do remember being struck by a very small country boy. How could this man have perpetrated that evil?

Williams: And then also, on the flip side of this, you covered the Supreme Court for many years. The swearing in of Justice Rehnquist by Justice Burger– I think that’s the ultimate action shot. How you did that– that’s also in the book– it’s one of the few Supreme Court action shots you’ll ever see. They’re sitting in their chairs, and there you have them standing up, they’re applauding, they’re moving, and you got all their likenesses down. How did you do that?

Kenny: I don’t know! But the other thing is that drawing the current Supreme Court– they’re often in swivel chairs, and some of the justices, like Scalia, will disappear from sight totally, lean back, and we are sort of in cubbies off to the side. So you speak of challenges, there’s one right there.

Another challenge was your having covered Martha Stewart and getting her face, even.

Williams: Oh, yeah, well, Martha was like the Russian spy. She didn’t look towards anybody. She was very far away. And courtroom 110 in the Manhattan Federal Courthouse is probably one of the most historic courtrooms– I don’t want to say in the country, but it’s quite historic. The Rosenbergs were tried there, the Mitchell, Stans case was tried there, Ivan Boesky was sentenced there, Martha Stewart was tried there, the Cannibal Cop was tried there. It’s a very historic courtroom, however, it’s very wide and large. Martha was on one side of the courtroom, and we were on the other. And she would look to her left, and meanwhile, we were on her right. Plus, the whole thing about Martha is the issue of Martha. When you have a famous person, and everybody knows what they look like, if you don’t get their likeness, everybody knows it. The thing about a person who’s attractive– they’re so hard to get because there’s no big nose, there’s no glasses, there’s no bushy beard…it’s a matter of just a millimeter here and a millimeter there. It’s either them, or it’s not.

Williams: You were in lockdown, right, with David Berkowitz in the Kings County Hospital?

Kenny: Yes. It was another era when we were allowed access that we are certainly not allowed today, post 9/11. We sat quite close to the defendant.

Williams: We’re still pretty close. I think the one issue is that the jury is pretty much off-limits now, which didn’t used to be the case. In the past, we were drawing juries in all sorts of mafia cases.

Kenny: I find it a disadvantage now when we can’t draw a jury, because often a courtroom composition can be pretty boring. And the foil of a jury for composition…

Williams: You’re the artist and I’m the illustrator [Laughs] Because your courtroom compositions are so gorgeous– I just approach it, like, ok what do we have to get in this picture?

I have a great story about Aggie [for the readers]– on the back of the Illustrated Courtroom book, there’s a beautiful still life painting of a watercolor box done by Aggie. That is just the most beautiful picture of a watercolor box, however, the main people–

Kenny: …like Westmoreland and David Boies…

Williams: –are not painted! It’s the watercolor painting. It’s a beautiful, beautiful painting.

Kenny: Well you have to sort of entertain yourself.

Williams: Well, you were probably there every day. I will venture a guess that you’d already probably done Westmoreland and that scene six ways to Sunday.

Kenny: It’s sort of like waiting for verdicts in the Sharon Trial. It ended up being sort of fun. They turned the heat off in the courthouse, we were there til late at night, but you had the leisure to draw the attorneys with their feet up on the desks. In that era, they were even smoking pipes in the courtroom.

Williams: There’s that nice drawing you did of Richard Tomlinson with the scarf around his neck.

Kenny: He was cold.

************

Elizabeth Williams

Elizabeth Williams’ artwork has been published on the cover of The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, USA Today, the New York Post and New York Newsday. Her work has been exhibited in juried shows at the Society of Illustrators in N.Y. and L.A. and The New York City Police Museum, John Jay School of Criminal Justice, N.Y., New Jersey’s William Brennan Courthouse and Conejo Art Museum, CA. The CUNY John Jay School Library acquired her folio of The Sean Bell trial for their collection. She has been featured in The New York Times, NY Metro and is the co-author of The Illustrated Courtroom: 50 Years of Court Art, published by CUNY Journalism Press. Clients have included NBC News, CBS News, ABC News, Associated Press, WCBS, WNBC, KABC, ESPN, CNBC, CNN and Newsday.

Aggie Kenny

Artist Aggie Kenny won an Emmy for her work on the Mitchell-Stans trial for the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite. Kenny covered the United States Supreme Court for over 30 years, and numerous other cases including: James Earl Ray, David Berkowitz ( Son of Sam), Oliver North, and the recent the trial of Jerry Sandusky. Her highly-regarded artwork of the World Trade Center responders, “Artist as Witness – the 9/11Responders,” was exhibited at The New York City Police Museum and in the US Senate Russell Building. Clients have included CBS, ABC, NBC, ESPN, PBS, CNN, Washington Post, New York Newsday, Reuters, Associated Press, Billboard and TV Guide.

Essay series founded and edited by Whitney Kimball. For more “Two Experts”, see links below:

Two Experts on Art Law

Two Experts on Renaissance Cosmetics

Two Experts on Sci Fi

Comments on this entry are closed.