This is the first story in a series covering art in the outer boroughs, “A Summer Without Manhattan.” I’m pleased to christen our celebration of all things New York that aren’t “New York, NY” with a return to the Farley clan’s ancestral homeland: The Bronx.

The Bedford Park Blvd./Lehman College subway station on the 4 train. These mosaics by Andrea Dezsö are a totally appropriate transition from the subway to the nearby botanical garden.

Paintings, plants, and glamorous leftist revolutionaries are probably the three things in the world that I get the most excited about. And so I had high hopes for Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life, a sprawling exhibition at the New York Botanical Garden that includes a Kahlo-inspired garden, ten oil paintings, some small works on paper, archival photos, and tie-ins like a tribute installation by Humberto Spíndola and Mexican dining al fresco.

I won’t say the show is a let-down because, really, it isn’t. The New York Botanical Garden clearly spared no expense; from compiling a veritable monograph worth of research to constructing a detailed simulacrum of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo’s beloved garden at the Casa Azul (the house where Kahlo spent most of her life, now a museum). Assembling any collection of Kahlo’s work is a Herculean feat unto itself, even for arts-specific institutions. There are only three other Kahlo paintings in museum collections in all of New York City, all of them at the MoMA. I will say, however, that the rare opportunity to see Kahlo’s work is seldom what I expect.

Making the trip to the Botanical Gardens is half the fun. Despite the hour-long subway ride from our office in Brooklyn and sprinting across several of the Bronx’s notoriously wide traffic arteries, arriving in the New York Botanical Gardens—250 acres of pastoral forests, Beaux-Arts structures, and greenhouses full of exotic plants—is remarkably calming.

The Kahlo-inspired garden and the actual artwork are somewhat disappointingly in separate areas—which, in retrospect should have been obvious considering oil paintings and Mexican flora survive in totally different humidity and lighting—and the conservatory almost steals the show. Set designer Scott Pask, curator Adriana Zavela, and the garden’s staff worked with museums in Mexico City and archival images to get a feel for what Kahlo’s Casa Azul garden was like when she and Diego Rivera lived there. They recreated Rivera’s pre-columbian-inspired pyramid, distinct blue stucco walls, and planted the conservatory with the native Mexican cacti and flowers Kahlo featured in her paintings. It’s such a pleasant place that I almost didn’t want to leave.

The paintings and works on paper are across the Botanical Garden campus, in a small gallery on the sixth floor of the garden’s library. With the exception of the show-stopper “Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird,” actually seeing the work here feels a little anti-climactic. The faint pieces on paper are roped-off and so dimly lit they might as well not be present. Mostly, though, the experience of seeing Kahlo’s paintings never seems to live up to the impossibly grand expectations we have for them. I was reminded of the last time I saw a Frida Kahlo exhibition after a much-longer journey than my crosstown adventure; in 2005 I went straight from the labyrinthian Heathrow Airport to her massive retrospective at the Tate Modern. At the time I blamed my jetlag for not feeling…something else. Here, though, I think I’ve come to the realization that Frida Kahlo’s paintings function very differently as physical objects than as the disembodied, iconic images we know and love.

We’re so accustomed to seeing Frida Kahlo’s work endlessly reproduced on postcards, enlarged on billboards, romanticized in films, and plastered on tote bags, T-shirts, and dorm-room walls. In a strange way, the images Kahlo produced have become icons that draw their power equally from their content and the cult of personality surrounding the artist. Strong Frida. Resilient Frida. Funny Frida. Bad-Ass Frida.

As physical objects, though, her paintings seem so tiny and vulnerable. Her cramped brushstrokes feel obsessive and introverted. They conjure an image of the artist in pain, struggling to negotiate between her internal world and the awkwardness of the physical. They suggest the limitations of the body as much as the strength of the will. They don’t bring to mind the Frida who drinks tequila with Socialist revolutionaries or has affairs with Josephine Baker, or confidently meets your gaze from the cover of Vogue. Many of her best paintings are small and controlled, not larger-than-life and wild like the woman we want to believe in.

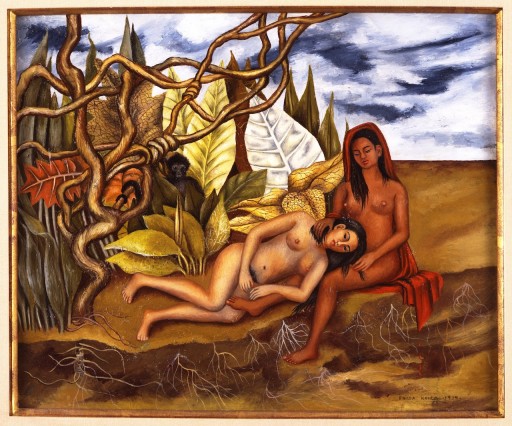

That’s not to say that Kahlo wasn’t a great painter, but the majority of the pieces here—culled from disparate museums and private collections—feel like “B”-sides. It’s difficult to see “Two Nudes in a Forest” from 1939 in the same room as “Self-Portrait Inside a Sunflower” from 1954. The two small oil paintings are almost exactly the same size. But while “Two Nudes” feels deliberate and composed—packed with all the nuanced texture and significant detail Kahlo is known for—”Sunflower” is scattered and empty. The colors (with the exception of some incongruous dashes of magenta) are muddy and broad, and uneven brushstrokes meander.

The paintings Kahlo produced later in her life, bed-ridden and woozy with painkillers—such as “Sunflower”—viscerally convey the suffering she sought to communicate through carefully rendered allegory in her earlier work. And, as a viewer, that’s not an easy thing to process—especially in the context of an exhibition with such a pleasant garden and so much biographical information and archival photos that reinforce how likeable the lucid Kahlo was.

Though it’s a small collection of paintings, the show is definitely worth seeing—and the garden alone is reason enough for the trip. (Remarkably, it was not at all crowded when I visited on a sunny afternoon—a welcome contrast to the long lines and jam-packed museums, galleries, and art fairs in Manhattan.) The rest of it—the tequila tie-ins, taco vendors, and Mexico City maps—at first felt like filler designed to make a small exhibition feel like more of an event than it is. I later learned that “Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life” was largely paid for by entities with a vested interest in the Mexican tourism industry, from airlines to Club Med. It’s an odd memorial for a feisty anticapitalist.

Comments on this entry are closed.