Philippe Parreno H {N}Y P N{Y} OSIS

Park Avenue Armory

Runs through August 2, 2015

A weary traveler might find respite in H {N}Y P N{Y} OSIS, a sometimes soothing, musical reverie held in the dark, cool space within the Park Avenue Armory. But just when she thinks she has stumbled into a calming oasis, those damn flashing lights won’t stop blinking, those automated pianos won’t stop playing, and those precocious little girls won’t stop speaking in existential overtones. That desert oasis was just a mirage—in H {N}Y P N{Y} OSIS, you’re actually in Disneyland coated in black-and-white hues.

Or something like that. It’s difficult to explain what H {N}Y P N{Y} OSIS is because there’s a lot going on inside the vast hall—all 55,000 sq. feet of it—situated in the Park Avenue Armory.

So you walk into a dark, cavernous hall, lit by a row of 26 hanging sculptures with lightbulbs affixed to them—together, called “Danny the Street.” They seem like automatons, with lights flashing in accordance with music that’s playing from…somewhere, maybe those pianos without pianists. Looking down the hall, there’s a circular set of bleachers you can sit on that slowly rotate. On three sides of the bleachers are projection screens that play Parreno’s films intermittently. Sometimes those screens are raised, then lowered; the roof also intermittently raises and lowers itself, providing natural light. The main purpose of the screens, though, is to play one of four films—although you never know when the screenings occur—which are more like still lifes with people in them sometimes. Then, within the rows of light bulb sculptures, you might chance upon “Anywhere Out in the World (2000),” one of the most well-known videos of Annlee, the well-known anime character whose copyright was purchased by Parreno and Pierre Huyghe in 1999 for $428, followed by performance artist Tino Sehgal’s interpretation—and reincarnation—of Annlee, simply titled “Annlee,” as three female pre-teen actors who walk around talking about how tiresome it is to be an individual. All this takes about three hours.

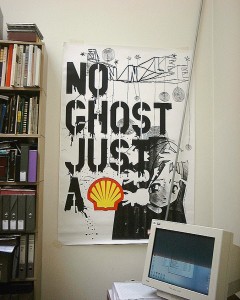

Poster from “Ann Lee: No Ghost, Just a Shell,” by Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe.

Confused? Yes, the exhibition feels like a structured performance in which the individual works of art compete for attention. Clarity is not the exhibition’s forte.

You never know what you’ll see next in the rotation of films, lightbulb sculptures, and child actors. Initially, I loved the exhibition when I walked into the darkened room. Lit only by the “Danny the Street” sculptures that seemed to have a life of their own, the work created what the press release accurately refers to as an “avenue of light.” The Park Avenue Armory seemed transformed into a cathedral interior, with the sculptures forming the nave. And that light, animated by the sculptures, was magical. Thrown into the crowded mix of the exhibition, though, the intrigue of this individual installation faded, and the first bit of magic was lost.

There are some great, individual parts to the exhibition. The films, for example, have a more concentrated aspect to them, informed by a sort of object-ontology. “Marilyn,” 2012, shows the starlet’s room at the Waldorf Astoria hotel, with a narrator constantly repeating descriptions of elements in the room—the colors of the walls, couch, and curtains—while someone scribbles a letter. You never see any humans. But the camera carefully pans so that you get a sense that these objects have a humanness to them, and perhaps, like humans, they have a “greater meaning,” too. At the end of the film, the camera zooms out to show that the interior of the room is only just a stage, and that there’s a gargantuan automaton writing the letters with one mechanical hand. Which means…? Human or technological, it’s impossible to tell the difference based on sheer product alone.

In another film, “June 8, 1968” (2009), the train voyage carrying former presidential candidate Robert Kennedy’s body from New York to Washington, D.C. seems to be shot from the point of view of the train. You see people lined up along the tracks to wave goodbye to the Kennedy who would not become President. But really, they’re just waving to the train—a big hunk of unfeeling steel they project their feelings onto.

Yes, the strength of these individual works is lessened by the exhibition as performance, with all the rotating benches, screens that flip up and down, and the unpredictable scheduling of work. Heck, it’d just be nice to know when the screenings occur. I’m all for plurality, but not of the cloudy type we get with H {N}Y P N{Y} OSIS. The exhibition needs to make up its mind.

is co-curated by Hans-Ulrich Obrist and Alex Poots, with consulting curator Tom Eccles Dramaturgy by Tino Sehgal, Philippe Parreno, and Asad Raza

Musical direction by Nicolas Becker and Mikhail Rudy

Piano performances by Mikhail Rudy

Sound design by Nicolas Becker, assisted by Cengiz Hartlap

Set design by Randall Peacock

Comments on this entry are closed.