Randi Shandroski at the ICA-Boston.

Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art [ICA] is one of my all-time favorite places to see art. Apart from having a gorgeous building, the programming and presentation here is almost always so on-point that I get resentful when I visit other museums that don’t get it this right.

It’s also nice to see an institution presenting a balance of international and local artists. I primarily went to the ICA to see Democratic Intuition by the Botswana-born, New York-based painter Meleko Mokgosi, which I’ll go into greater detail about in another post. I ended up really loving the ICA’s two other exhibitions: a retrospective of the New York ceramicist Arlene Shechet’s 20-year career and the biennial James and Audrey Foster Prize exhibition, which recognizes Boston-area artists. This year’s Foster Prize focused on collaborative or performance-based practice and was awarded to Ricardo De Lima, Vela Phelan, Sandrine Schaefer, and the collective kijidome—which I had been told was one of the pillars of the Boston art scene.

For the biennial, kijidome converted their South End exhibition space into a rotating studio residency for invited artists, whose work was then curated into the ICA’s galleries in phases. It was a great strategy to showcase the collective’s utility as cultural facilitators rather than focusing on individual members’ studio practices. The resulting show focused on process-based works and stages of building—appropriately dialoguing with a lot of the work I saw in galleries in the collective’s own neighborhood. The aesthetic zeitgeist of Boston at the moment seems to be colorful grid-like work that references architecture and construction. On some level that makes sense, as so many of the artists I spoke with in Boston, as in most contemporary cities, are concerned about gentrification and the fate of their neighborhoods. Perhaps many artists have subconsciously taken to being their own architects, contractors, and urban planners in their studio practices as we feel less and less control or ownership over the outside world.

Sean Glover, one of the artists hosted by kijidome, paints construction detritus such as insulation foam and drywall. This diorama changes a lot as one walks around it—at times it reads as a painterly abstract collage and from other vantage points it looks like a cityscape in some stage of construction or demolition. The impression of anxiety over urban futures is reinforced by the piece’s title “…Let’s not Think about Tomorrow.”

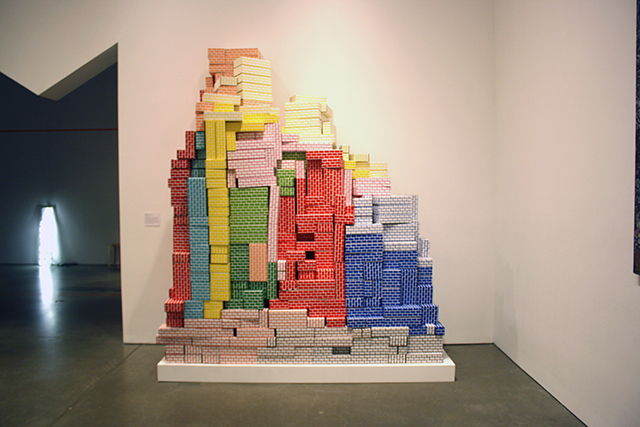

There’s an obvious visual correlation to Jennifer Schmidt’s work. Schmidt used her kijidome residency to fabricate cardboard blocks (like the ones from childhood construction sets). I like the play between a printed surface being made into an object that’s then used to construct a form that reads as a graphic, painting-like composition.

Randi Shandroski, another kijidome-selected artist, frames her practice as design for a conceptual fashion house/corporation called Lactic Incorporated. A lot of the digitally printed fabric has a Dis Magazine/normcore vibe, but that corporate sterility is mediated by the artist’s own mark-making, visible traces of her hand in the craftsmanship, and visceral imagery. Some of the prints are recycled advertising banners. There are traces of idealized flesh and luxury condos stitched into one dystopian consumer nightmare—through fiber arts techniques Shandroski queers the “dream home” and “dream body.”

I love how the consumer language is interrupted with lumpy, organic allusions to the body. Sex may sell, but there’s something deeply unsettling by these ersatz mounds of flesh modeling misshapen flip-flops. The whole thing is a great subversion of marketing.

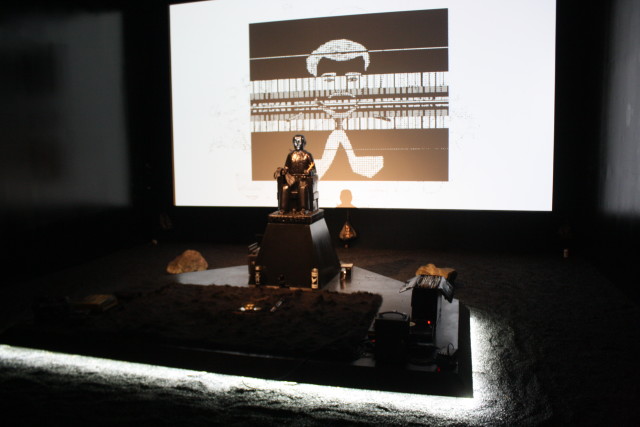

It took me a minute to warm up to Michael Jones McKean’s work. I think I was at first off-put by the very pseudo-shamanistic vibe in a didactic-looking container. I’m not sure if this is the intent, but I thought of dioramas in natural history museums, where non-western culture has historically been curated as part of “nature” rather than art history. Here though, there’s a white man (perhaps the artist?) on display in an assemblage titled “The Ceremony.” That association was reinforced by seeing this work in the same day as Meleko Mokgosi’s show—even though Mokgosi lives and works in New York (where he’s on the faculty at NYU) and has an MFA from UCLA, the Botswana-born artist’s practice is frequently framed through a somewhat anthropological gaze.

With a similarly ritualistic tone, Foster Prize recipient Vela Phelan’s all-black room is a strange pastiche of devotional objects. Santeria candles, a black leather recliner, and animal antlers that join Victorian cameos with obscured faces in a room that feels like a Witch House man-cave. The whole space is filled with black gravel, garbled music, and extremely dim lighting. It’s pretty fun to hang out in. Apparently, Phelan has been coming to the space to periodically perform ceremonies in front of the flashing video portrait—an altar to Jesús Malverde, a Robin Hood-esque figure from Sinaloa who is remembered almost as a folk saint by Mexican narco-cartels. There are a lot of layers of ambiguity here. Mostly, it looks really good. Appropriately, it’s probably the best room in the museum to do drugs.

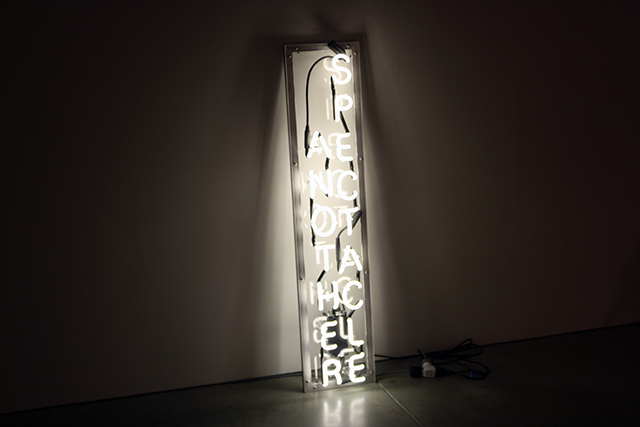

Ricardo DeLima has also been staging events and performances in the ICA as part of his Foster Prize exhibition. When the artist isn’t present, this neon sign that reads “ANOTHER SPECTACLE” serves as a kind of placeholder. I like that neon has become a sculptural image that establishes a performative site, similar to Meghan Gordon’s “SOMETIMES” project.

In addition to the Foster Prize, the museum is also hosting a retrospective of the sculptor Arlene Shechet. Shechet is so prolific that it’s mind-boggling. Her ceramics wildly range in size, and style and fill several galleries. These pieces are from a few years ago and totally pre-date the contemporary trend of giant metallic meteorites and painterly ceramics we saw at Frieze this year.

This piece is one of my favorites, and could’ve comfortably lived in the same room as kijidome’s architecturally-inspired selections.

Knowing that the piece is ceramic gives this even more of a precarious feeling—as if a favela is about to slide off a soggy hill.

These look like a lot of the paintings I saw around town, but they’re actually bas reliefs made from casting Shechet’s studio debris in colored paper pulp. One of the aspects that’s consistently impressive about Shechet’s oeuvre is her capacity to create painterly surfaces with sculptural techniques.

Comments on this entry are closed.