It’s hard to count all the ways the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) exhibition “Andy Warhol: Stars of the Silver Screen” fails. Lame gallery space, obvious exhibition design, poor exhibition maintenance all contribute to a terrible viewing experience. And it’s not the first time. The show is the latest in a string of underwhelming shows suggesting that the film centre and headquarters for TIFF might not be equipped to handle the major touring exhibitions it earnestly seeks to attract. In the five years since TIFF moved into the TIFF Bell Lightbox, a five-story glass-paneled complex in the heart of city’s entertainment district, its exhibition programming has struggled in going year-round.

Blame the HSBC Gallery, its main exhibition space. Despite state-of-the-art cinemas on upper levels gently twisting above an airy street level public atrium, it’s always struck me as an architectural afterthought. Any exhibitions I’ve seen — from a revamped version of MoMA’s Tim Burton exhibition to the TIFF-organized David Cronenberg retrospective survey — have felt cramped, and marred by exhibition design lacking any sort of intuitive flow or sense of movement for visitors.

This impression was affirmed when I visited Andy Warhol: Stars of the Silver Screen on a Sunday afternoon, a week after its October 30 opening. For a show teeming with Warhol’s Hollywood memorabilia—the show is organized by the Andy Warhol Museum and includes over 800 artifacts and loaned artworks—it should be an easy success story. At first glance, the exhibition is “basic” Warholian. When you enter, you’re boxed into a mirror paneled corner, forced to gaze at a photographic blow-up of an early 1960s Warhol holding up a Marilyn acetate. Factory production, the churning out of product: this exhibition is about Warhol’s meat and potatoes; silkscreen celebrity portraits and serialized pop culture iconography in the main space, and durational film work in a separate smaller gallery.

In the main gallery space, one wall was dominated with a salon-style hanging of star and superstar glossy headshots. But the central display lacked any didactic information. Despite helpful gallery attendants circulating the floor, I still overheard a visitor complain, “I wish there was more explanation of the photos.” Such an obvious oversight don’t happen at most museums, and they shouldn’t happen here.

Toward the back of the main gallery space, glass doors lead into a smaller gallery space faithfully turned into a recreation of the Factory: think red casting couch, silver walls, and band gear alluding to a rehearsal for an upcoming Exploding Plastic Inevitable gig. Boilerplate Warhol, but appropriate for the general audience who would view it. It was also the staging for his film work. TIFF has a lot running on this given who they are, and thus expanded the exhibition to include two film programmes: the TIFF Cinematheque’s Liz & Marilyn series and a selection of Warhol-directed films. So far, I’ve enjoyed the Mario Montez starring Harlot and the delightfully high camp Liz Taylor masterpiece BOOM!. According to didactics, many of the smaller screens with headphones were supposedly playing a Warhol screen test or Factory Diary or even an episode from either one of his 1980s television talk show. But why on my visit to the exhibition only a week after its opening were a significant amount out of commission? It was like encountering an amateur show at the tail end of its exhibition run.

Just outside this Factory space, I overheard another visitor demanding to an attendant with an exasperated tone, “where can I take the screen test?” The exhibition’s highly-promoted interactive “Screen Test Machine”, a take off on Warhol’s silent film portraits, was nearly impossible to find. It turns out you have to wind your way back outside the main exhibition space, near the gift shop and another bunch of out-of-commission screens, to a squat, blocked off non-descript concrete corner.

On top of all these misses, the obscure way-finding to moving image installations of Warhol-inspired works by contemporary artists on the Lightbox’s upper levels ensured most audiences never saw this part of the show.

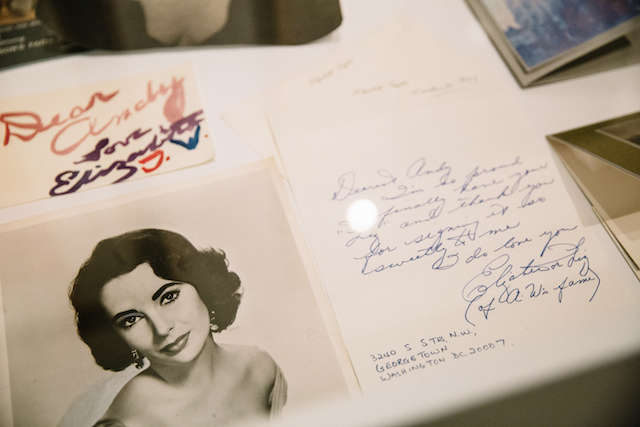

What a missed opportunity. Aside from the starfucking you already know about, the show gives viewers a window into Andy Warhol’s die-hard fandom. In the fannish continuum of Golden Age Hollywood celebrity culture, Warhol straddled between being both an enthusiast and cultist. One of the first vitrines visitors encounter contain his sacrament-like scrapbooks, filled with celebrity autographs and magazine pin-ups, tracing a baptism to confirmation narrative of a gay but also devoutly Catholic artist. A colour-tinted 1930s Shirley Temple headshot is addressed in careful cursive to “Andrew Warhola.” Later on, when you see a collection of similarly colour-tinted 1970s Interview Magazine covers, you get the full circle of his religiosity: movie stars were his icons of worship. His absorption of the Hollywood Golden Age studio system served both a spiritual and ethical framework for his artistic output.

Much of the memorabilia points to Warhol as pack rat. For the past ten years, the Warhol Museum has been indexing items from his Time Capsules, a collecting project begun in the mid-1970s and continued until his death where over 600 cardboard boxes were filled with the artist’s everyday ephemera: correspondences, photographs, newspapers, magazines, even Fiestaware. Although Warhol envisioned these boxes as works of art, they never went to market; in the meantime, his museum has made the opening of these boxes public events.

Of all the material on view, I was most fixated on his framed film posters— particularly, 48 Hours and Videodrone. If you’ve read the Warhol Diaries, you know he regularly watched Entertainment Tonight, Letterman and thought the New York Post gossip column made his nights out sound way better than what they really were. For vitrines loaded with celebrity tell-all hardcovers, Clark Gables’s shoes and a Elizabeth Taylor-signed “Peace, love and serenity” Christmas card, the exhibition perhaps could have used the space’s claustrophobic walls to its advantage, and delved deeper into another less popular Warholian theme: hoarding. It’s a problem both fans and collectors share, and a unique opportunity for TIFF to distinguish itself as a forward-thinking institution.

But as long as they keep up an exhibition programme propped with touring shows, and continue to ignore the need to drastically re-assess the exhibition designs in their HSBC space, that’s not going to happen.

Comments on this entry are closed.