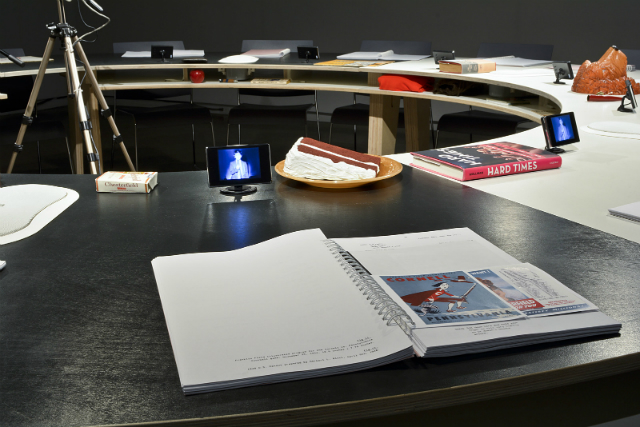

Alison S.M. Kobayashi, Say Something Bunny!. Installation view at Gallery TPW, 2016. Credit: Gallery TPW

History needs historians. They chronicle the past, poking and prodding at the accumulated details that ultimately defines public record. What’s perhaps less obvious, though, is that history needs artists too.

At least that’s the conclusion I drew after visiting Say Something Bunny!, Alison S.M. Kobayashi’s solo show at Toronto artist-run center Gallery TPW. Having received from a friend a 64 year old wire recording purchased at an estate sale, the Toronto and Brooklyn-based artist manages to unspool a multigenerational yarn of Rothian heights. The audio, augmented by Kobayashi’s rigorous and thorough research, uncovers the trials and tribulations of a middle class Jewish family from Long Island. Throughout the installation, Kobayashi renders the facts that define the lives of these idiosyncratic cast of characters deeply felt and most remarkably, close and real.

She does this by re-staging the recording as a cold reading. The performance and exhibition treats the organized reading around a round table of a playscript as a throwback to the now out-of-print Read-A-Long Adventures. A large-scale projection dominates the space. In front, tables positioned in a hollow circular set-up become the staging for 15 script copies. Small screens flash the corresponding page number of the script to the audio recording playing overheard. The cross-talking Long Island-accented voices heard in the recording reverberates throughout the gallery.

Alison S.M. Kobayashi, Say Something Bunny!. Installation view at Gallery TPW, 2016. Credit: Gallery TPW

Even without the content, the presentation alone would be compelling. But a little examination goes a long way. Kobayashi names script covers for particular characters and matches them with found objects. The great aunt who likes to party pairs appropriately with an elegant set of crystal cordial glassware. A hardcover copy of Hard Times: The Adult Musical in 1970s New York City next to the father who we eventually will learn died too young to see his sons become men. Some of these pairings seem more arranged than others. For instance, Kobayashi stuffs an apple, a bit of wrapping paper, a brunette wig and other props within the open desk storage. They’re mostly hidden, giving the sense that stories are buried and must be excavated.

The work’s form is true to its subject. Kobayashi splits the script into two acts, corresponding to the fact that the recording is actually a composite of two recordings made during a 1952 and 1954 holiday gathering, respectively. David, owner of the wire recorder, takes on the same profession as Kobayashi’s medium of choice: a playwright and lyricist.

Throughout the recording we’re given a sense of the characters’ relationships to each other. David is the son of George and Juliette, older brother of Larry, grandson of Sam and Stella. The conversations heard — at one point, regarding the 1954 Broadway musical Fanny, or a toast to Stella and Sam’s 44th anniversary — are at first mundane, even unremarkable.

Alison S.M. Kobayashi, Say Something Bunny!. Installation view at Gallery TPW, 2016. Credit: Gallery TPW

There are moments, however, that seem all the more human through Kobayashi’s research.

Periodically, the recording is interrupted by the projection of Kobayashi sharing salient details uncovered by her research: a census record clarifying the distinction between family members and neighbours, or the artist appearing, with haunched stature and askew balding man cap and wig, as the grandfather Sam we hear overhead marvelling over the unique colored pants Sam gifted him (“chemanamaneurian” — to which his great aunt Florence squawks, “sounds like horse manure!” — and Kobayashi eventually determines is unique because it was an invented shade).

When George quietly shares with another family member that he’s on medication for his diarrhea and anemia, Kobayashi interrupts to connect the father’s hushed aside to being early symptoms of lung cancer. The projection then flashes to footage of George’s gravestone. He died in 1959, four years after the recording, at 55 years old. She — and we, in a sense — have become so committed to the narrative that when she asks “George, have you told your sons you are sick?” It’s not an untoward question. The confident youthful assurance of the David heard in the recording contrasts with the wayward career Kobayashi uncovers — an earlier blast from the embedded table speakers of a rare Petula Clark 1970 b-side (“Big Love Sale,” co-written by David) is thunked by his later career less than ten years later as a writer of adult musicals and eventually forgotten video porn.

At one point, Kobayashi mentions she uncovered 32,155 documents, all of which were public records and journalistic accounts. Only a professional level-researcher could unearth so much information, yet there’s a disarming amateurism to the way in which Kobayashi brings to life the characters. Her costuming is DIY and her research employs rudimentary tools—she herself describes the project as being informed by “amateur historical research”. But with those imperfections she brings humanity and life to her subjects. Indeed while facts of this story define public record, it is context that Kobayashi’s art provides that bring these histories to life.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 2 trackbacks }