The original image has been removed at the request of the owner

One of the most common questions artists ask each other at openings is, “Where do you live?” Perhaps equivalent to the typical New Yorker’s “What do you do?”, most of the artists I’m meeting these days live in Brooklyn. On the rare occasion an artist like me answers “Manhattan,” eyebrows raise.

At least this has been my recent experience, so I quickly caveat with, “I won the housing lottery.” This usually provokes responses like, “Wow, that’s like winning the lottery!” Yes, it is. In fact, the odds were approximately 0.06%.

The Affordable Housing lottery in NYC provides inclusionary housing to lower-income tenants within newly constructed buildings. Also known as “80/20,” this tax-incentive for real estate developers is a major initiative of NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio, who wants to add/maintain 200,000 affordable housing units over the next decade.

But being a lottery winner isn’t all limos and 6,000 square foot living rooms. There has been a lot of debate amongst housing activists about the effectiveness of a program that serves so few, and don’t even get me started on how “low-income” is calculated based on the median income of an already wealthy neighborhood. That said, because I was drawn as one of the lucky 55 of 88,000+ applications in the lottery, and managed to conquer the near impossible mound of paperwork required, I now live in riverfront property. I was offered a unit in 40 Riverside Boulevard near Lincoln Center.

Woo hoo, right? Well, not so fast. The notorious developer, Extell, brands the building as “One Riverside,” but split the building into two separate entrances, and thus two addresses—the other being on 62nd Street. I now live in one of two buildings in New York with “poor doors”.

One Riverside Boulevard

Not to sound ungrateful, but the “Poor Door” depresses me. It’s dubbed for its apartheid entrances, one welcoming condo-owning tenants through a lavish doorman entrance facing the Hudson River, while the other segregates affordable housing renters through a non-descript side door. On paper this makes some sense, as penthouse residences sell for over $23 million, boasting 6 bedrooms and 8.5 bathrooms. The 2-bedrooms in the “Poor Door” rent for mere $1,082 per month to families of four who earn less in total than $50,000 per year.

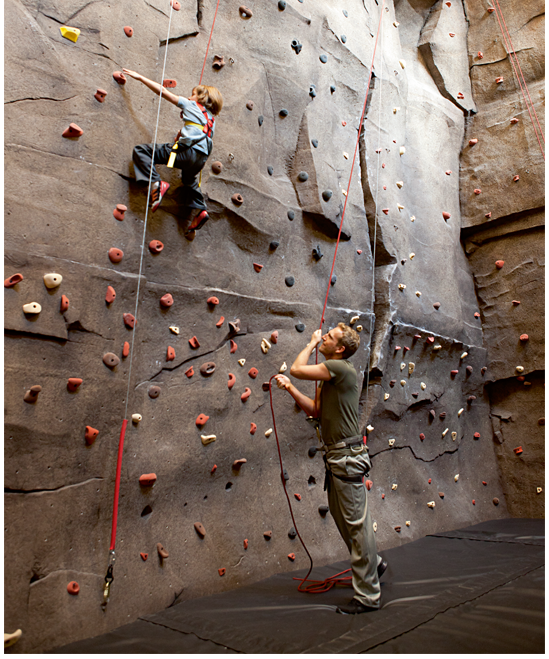

As a “Poor Door” resident, I do not have access to any amenities or services: doorman, live-in super, courtyard, media theater, gym (rock-climbing, indoor playground, squash, tennis, golf simulator, bowling alley), spa, pool, and even two hot tubs on the roof! I didn’t pay $23 million for my apartment, so I understand that I don’t get to drink champagne in the hot tubs, but living in a building that literally engages in segregation doesn’t feel good.

Private Penthouse Pool in One Riverside

Rock Climbing Wall in One Riverside

This is all further complicated by neighborhood and real estate development politics. The building shares 62nd Street with public housing projects, and foot traffic is warded off by a chain-link fence, a painful geographical reminder of the class divide. Soon after I moved in, Extell sold the “poor” side of the building to Breaking Ground, a non-profit housing agency. Breaking Ground management is understaffed, thus slow to make repairs and complete construction. For example, the only two promised amenities in the building, a laundry room and bike storage remain to be finished. It’s been over half a year since the building opened.

That’s not the only issue that plagues the development. The “Poor Door” entrance is camouflaged by the parking garage for One Riverside, so deliveries are constantly getting lost. Once the all-boys private high school, Collegiate School, finishes construction on the other side of the “Poor Door,” that half of the building will be completely erased from the Riverside skyline, further obscuring the architecture from identification. Weirder yet, despite being open for six months, less than half of the 55 units are currently occupied.

I do not feel at home here. I am an unwelcome foreigner based on my income alone (forget the fact I may be a professor to some of the neighborhood rich kids in the future.) An adorable interracial family has just moved onto my floor, and the mother worries about how to raise their baby with dignity in the “Poor Door.” So far, the only interaction I’ve had with neighbors from the other side was when a young lawyer helped me call an ambulance late at night for a fancy business man passed out drunk on the street. When the young lawyer asked me where I lived, I pointed to the same building he lives in, staying silent about which side.

Given my experiences over the last several months, I cannot help but question the legacy de Blaisio will leave behind. Nobody I’ve spoken to in the building feels completely at home, and that discomfort is accompanied with the burden of guilt for not properly appreciating the gift we’ve been given. It’s not insignificant to my life as a working artist in New York that I no longer have to stress out about rent. But it’s also not insignificant that my own home imposes undue shame on the artist life that I’ve chosen. Indeed, the fortune we have been bestowed is mixed at best.

Comments on this entry are closed.