Rodney McMillian, “Many Moons,” 2015. Latex, acrylic, and ink on paper mounted on fabric.

ICA Philadelphia

118 S 36th St, Philadelphia, PA

All shows up until August 14th

What’s on view: Rodney McMillian: The Black Show, a solo exhibition; Paper Louise Tiny Fishman Rock, a retrospective of the Philadelphia-born painter Louise Fishman; Descent, a group show about “inheritance” organized by Whitney-Lauder Curatorial Fellow Charlotte Ickes; and Open Video Call, a selection of work from local video artists.

Michael: Confession—I don’t think we actually sat through any of the work in Open Video Call, which is unfortunate because in retrospect it sounds really promising. The show was juried by Alex Da Corte, Tiona McClodden, and Vox Populi’s executive director Bree Pickering. But after seeing The Black Show and Descent, two media-heavy exhibitions, I don’t think either of us were up to the challenges posed by viewing more video work at the ICA. Namely, there’s too much of it for an institution with not-so-great acoustics. In nearly every gallery the audio tracks from multiple pieces overlap and echo to the point of incoherence, in some cases

Whitney: Yes! Rodney McMillian’s Gimme Shelter in the main gallery: the whole point of that video is a distortion of the Rolling Stones song, which you could only hear if you were standing directly underneath a speaker on the ceiling. And that was totally drowned out by overlapping audio from other video and the docent tour. I know, wah wah wah, acoustics, but in this case, it really was a problem. That video is a centerpiece.

Michael: And this much time-based media in one serving is asking a lot of the viewer, even under the best circumstances. That’s not necessarily a commentary on the quality of the work here—if anything, we were really impressed with certain pieces—it’s just unfortunate scheduling to have so many video-centric shows playing at the same time in one small building.

Rodney McMillian, “The Black Show” installation view with “Many Moons” (left), “Column,” and “A Migration Tale” (right).

Rodney McMillan: The Black Show

What’s on view: A video of the artist crawling through grass singing a tortured version of “Gimme Shelter”; A video of a person migrating from a porch in South Carolina to Harlem in a chrome alien hockey mask and black robe; Various black pleathers and fabric hangings and black-and-burlap flag

Michael: First impressions walking into The Black Show: the space is hung so well. The way the videos are suspended and “Many Moons,” a giant curtain/painting, bisects the gallery is really special. The huge piece is almost like a backdrop, ambiguously showing us a forest or perhaps river delta, tributaries, or blood capillaries. All might be appropriate to the narrative here. The surface is beautifully marbleized, viscous paint. It’s one of the strongest physical pieces in the show.

Whitney: There are a lot of familiar aesthetics here, reminiscent from nineties identity politics: a distorted American flag and distorted American rock music, violently chopped-and-sewed murals of pleather-y and rough fabrics. But McMillian’s video A Migration Tale– in which a cloaked figure in a chrome alien hockey mask travels from South Carolina to Harlem– happened to make a really timely book end to American Reflexxx. In that video, a tall woman in a sexy dress and chrome mask walks down Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, and is beaten and bloodied by a mob of transphobic women and children. In New York, McMillian blends right in.

Also, the security guard pointed out to me that a woman in a New York City subway scene was reading The Color Purple. Whether the reader was a plant or not, it was a nice little nod that the whole country isn’t totally shitty and ignorant.

Michael: I also immediately thought of American Reflexxx, and kept bracing myself for some act of violence, riveted. But unlike Signe Pierce, the figure didn’t seem to encounter any other people in his time in South Carolina. The place seemed eerily deserted.

Whitney: I do wish we’d gotten more of the traveler (described as “part Ultraman, part cassock-garbed priest”) walking around in South Carolina for comparison– I think the only real street-level stuff we got was him walking down the steps of the state capitol building. But anyway…

Michael: In New York, he’s largely ignored on a crowded subway car (we’ve all seen weirder) and finally makes his way to a drum circle/outdoor dance party, where a woman dances with him really, really enthusiastically. It’s hard to watch this and not smile—especially after anticipating something horrible happening. After he finds “his people,” the masked figure sits alone, seemingly peacefully, in a bucolic section of Central Park. Perhaps he’s reminiscing about his more-pastoral home. The world’s a place of traumatic diasporas and migrations, but there’s someone for everybody in the cities where all the marginalized or transient or just-plain-weird end up trickling into.

Rodney McMillian, still from “A Migration Tale”

It is impossible to not compare this experience to Pierce’s. Both artists start off in South Carolina, obscuring their faces with mirrored masks. In McMillan’s case, every aspect of his identity is utterly disguised. We have no indication of the figure’s race or gender, really. And he’s accepted or tolerated by strangers. Sadly, McMillan probably faced less threat of violence/harassment from the NYPD as an anonymous “other” in a “threatening” Halloween mask than as a black male. He can ride the subway incognito to find a space of liberation, like an oddly literal translation of the Underground Railroad story. But in Pierce’s piece, her body is exposed and presenting as female—only her individual identity is erased. That alone is enough to provoke mob violence. There’s so much to unpack in these accidentally-dialoguing videos… I don’t think I’ll ever understand the “logic” of how people identify who to fear or hate.

Whitney: Totally. I wonder how McMillian would have been received at Myrtle Beach. Would people have recognized the black robe and mask as the slasher from Scream or a villain from Star Wars? Ironically I think that would have been less upsetting than the possibility of a queer or transgender person.

Michael: I couldn’t stop thinking about A Migration Tale for days, even as I binge-watched the new season of Orange is the New Black over the weekend. There’s a tear-inducing flashback episode that made me think of the piece. We finally get to see a happy night in the otherwise tragic story of an itinerant queer black character. Alone in New York, she meets this broad array of personalities and bonds with unexpected strangers—the whole sequence perfectly captures what it’s like to arrive in the city and surrender inhibitions and discover a world of possibilities as a young queer person. The episode ends with her standing on the East River waterfront, beaming and utterly at peace. But when the credits start rolling, there’s a gut-wrenching realization that this is the moment right before she’s arrested (for bullshit reasons) and her life is ruined. We like to think of America’s great cities as these spaces of acceptance and liberation for marginalized people, but the reality is the police state and all associated mechanisms are rigged to fuck over black people. It makes me wonder what the epilogue to A Migration Tale would be. What happens when the figure removes his mask? Is the promise of freedom in the North a bittersweet myth?

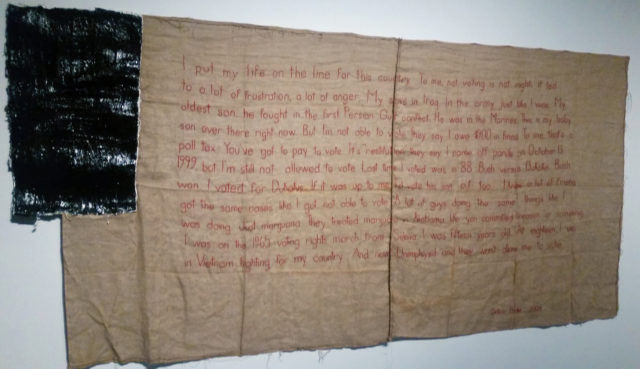

Rodney McMillian, “Untitled (Flag IV),” Burlap, thread, plaster, latex, 2012.

Whitney: I tuned out when the docent started talking about the “horizontality” of the stripes, pointing out how this piece turns a familiar patriotic symbol on its face, etc, etc. The security guard turned to me and said “it’s about color.” That’s enough.

Michael: This piece made me pretty angry-sad. The stripes are an embroidered story from a veteran who was arrested for marijuana possession and hasn’t been able to vote for years. I like this piece, but I’d find it a lot more subversive if the aesthetic had been closer to a fabricated store-bought flag instead of the crafty “outsider” look we so often see affixed to work about oppression. I also tuned out when that guided tour group was passing by… something about “If they had shown this where I went to school, at Berkley…” but the “horizontality” just made me realize the rectangle where the stars should be has been rotated to an orientation suggesting “portrait” and blacked-out. That’s a subtle but important move.

Louise Fishman

Paper Louise Tiny Fishman Rock

What’s on view: Countless tiny abstract canvasses (mostly just a few square inches) and a handful of abstract sculptures alongside vitrines with works on paper and other ephemera spanning the artist’s 50+ year career.

Michael: I’m so confused by this show’s curatorial intent. The exhibition text makes it sound like a retrospective of a celebrated artist but also describes a show “conceived as a studio visit: a chance for viewers to see bodies of work that represent a largely private practice.” We’re told the exhibition positions this work in dialogue with “the artist’s Philadelphia roots, her feminist and queer politics, Jewish identity”. I’m not quite convinced these abstract works have anything to do with identity politics, especially after viewing a powerful identity-informed exhibition like The Black Show. Must all of art history be revisited through the frame of the contemporary concerns du jour? Maybe sometimes painters are “just” painting, and that should be enough.

Whitney: Yeah, what??

Admittedly I wasn’t aware of Louise Fishman’s prominence in Neo-expressionist and Minimalist circles– relationships with Agnes Martin and Eva Hesse are mentioned in the press release– which I suppose explains why a collection of odds and ends and tiny sculptures are significant? At the risk of sounding like a philistine, I’m unconvinced that rushed brushstrokes on crumpled paper and rocks are necessary to revisit, even if they informed her practice.

And the ICA does present that case. They write that the small works were a way of getting over the impulse to make small-scale female-identified work, “grant[ing] herself permission to paint on the heroic scale with the freedom she now possesses.”

But then they throw this in the mix:

“There will also be some very early works, including a self-portrait of the artist as a blonde boxer.”

So the curatorial thrust is: “hey, why not?” There’s no overarching theme or investigation here, together it’s an uneven scattering of unfinished thoughts.

But maybe this show is for Fishman fans who already want the B-sides. Or maybe I’m just size-ist.

Michael: Is the message that accumulation (regardless of apparent quality) or prolificness are queer/feminist/”other” qualities distinct from what other (mostly male) painters were doing at the time? I’m not sure I buy that. But showing a huge array of these paintings makes them look like they came from an assembly line and there’s no sense of importance or intimacy to the individual canvasses. If anything, small-scale and intimacy are what differentiate these works from “macho” ab-ex. That gets lost here. I really like the tiny painting above, for example, but it’s hard to spend time with it when it’s contextualized in a room of similar-looking stuff of uneven quality. I wish there was some type of more evident progression or narrative to the way the work was hung.

Karina Aguilera Skvirsky “Los poemas que declamaba mi mamá (The Poems My Mother Recited)” 2010-present.

Descent

Runo Lagomarsino, Matriarch (Maren Hassinger and Ava Hassinger), Virginia Overton, Karina Aguilera Skvirsky, Lisa Tan

Curated by Charlotte Ickes

What’s on view: An installation of museum detritus packed into circles framing videos of Philadelphia streetscapes from Matriarch, A slide projection and audio recording from Karina Aguilera Skvirsky, a wall covered in cedar planks by Virginia Overton, videos screening in black box theaters.

Michael: All of the artists in this show deal with the idea of an inheritance in one way or another. Mother-daughter team Matriarch organized the ICA’s own leftover installation detritus into circles around video screens. Karina Aguilera Skvirsky projected black and white photos of her mother, who was a reputable poet in Ecuador, onto a green rectangle accompanied by an audio track of the artist reciting the poems. I like this piece, because it’s a nice balance of feeling complete and anti-monumental, if that makes any sense. It’s just this nice moment, a kind of family slideshow, despite the dramatic delivery of the reading. It’s so pleasant to stand in front of. But this is definitely one of the more problematic spots for sound… it’s especially challenging to overhear multiple audio sources in different languages.

Whitney: Yes, again, sound is a problem. Even in the cordoned-off video room, showing Runo Lagomarsino and his father egging a statue of Christopher Columbus, it was like the speakers were coming from the hallway inside a sock. Not that we particularly needed sound for that piece, but it was distracting.

We walked in at the climax, where father and son are each throwing a carton of six eggs at a weird monument to Christopher Columbus holding up a map inside of an egg-like structure. Then we dutifully stood through a few long anti-climactic minutes of the two taking a long walk up to the statue, unwrapping each individual egg, and, having done the deed, walking leisurely off into the distance.

Runo Lagomarsino, still from “More Delicate Than the Historians are the Map-makers Colours,” 2012-2013.

But Lagomarsino had a lot more content than the video lets on; we learn in the written materials that previously the eggs had taken a trip around the world from Buenos Aires up to São Paulo and east to Seville. How hilarious would it have been to watch a dozen eggs preciously transported up the coast of South America and across the Atlantic, only to get thrown at a Christopher Columbus statue? Knowing that makes the act much more cathartic, so I wish that background weren’t forever stuck in a press release, destined to follow the video around the globe.

Michael: I will never understand most people’s editing priorities. Wouldn’t most videos be so much better as short GIFs? Anyway, I think it’s interesting that “egg of Columbus” is an expression that refers to a revolutionary discovery that actually seems pretty unimpressive in retrospect, like “Well, someone from Europe would’ve ended up across the Atlantic someday anyway.” I think this is a smart piece, because it deals with a lot of the conflicted post-colonial resentment those of us of European descent who were (obviously) non-consensually born in the Americas feel. The Lagomarsino’s are returning the egg (or the fatherland’s sperm) to the source, so to speak. The piece could cut to the chase a little faster, but I have to admit it was pretty cute that they politely packed up their trash and took it with them when they walked off giggling like teenagers into the sunrise.

Comments on this entry are closed.