Hartmut Beifuss, Charlotte Moorman performing Nam June Paik’s TV Bed, Bochum Art Week, Bochum, West Germany, 1973, Digital print, Peter Wenzel Collection. © Hartmut Beifuss (all images courtesy the Grey Art Gallery)

A Feast of Astonishments: Charlotte Moorman and the Avant-Garde 1960s-1980s

Grey Art Gallery

100 Washington Square East, New York, NY

On view until December 10, 2016

Resurrecting the forgotten careers of women artists can make for bittersweet exhibitions. On one hand, it’s exciting when a visionary woman finally gets the attention she deserves. On the other hand, the institutionalized sexism that erased her creative input is thoroughly enraging.

Nowhere is this felt more intensely than in A Feast of Astonishments: Charlotte Moorman and the Avant-Garde 1960s-1980s, currently at the Grey Art Gallery. Organized by a curatorial team largely connected to Northwestern University (the show first premiered at their Mary & Leigh Block Museum of Art), the expansive exhibition firmly establishes Charlotte Moorman as a performance art force alongside seminal Fluxus artists like Nam June Paik, John Cage and Yoko Ono. In a response to art historical misogyny, the show essentially returns her artistic agency 25 years after her death in 1991.

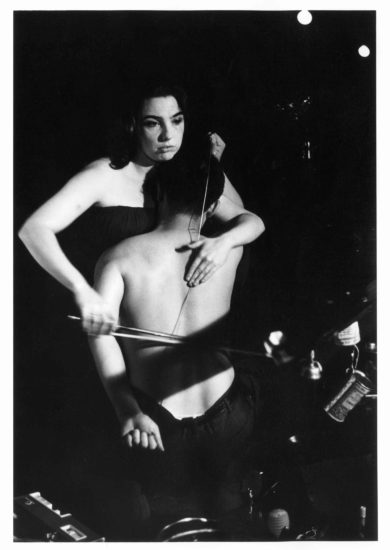

If you have no clue who Charlotte Moorman was, don’t worry. You’re not alone. Despite her stature amongst her peers, Moorman rarely appears in textbooks and has a limited show history. That’s weird, even knowing that raging misogyny has literally transformed history. You’d think someone with the nickname “The Topless Cellist” might transcend a few boundaries like this.

Charlotte Moorman performing on Nam June Paik’s TV Cello wearing TV Glasses, Bonino Gallery, New York City, 1971, Photo: Takahiko Iimura. © Takahiko Iimura

As this exhibition shows, though, she’s left an astounding legacy. Through a range of photographs, videos, sculptural cellos, banners and assorted ephemera from Moorman’s archives held at Northwestern’s library, the exhibition introduces Moorman as a one-woman powerhouse. She was a classically trained cellist, a multidisciplinary artist, the organizer of fifteen incarnations of the Annual Avant Garde Festival of New York and an all-around badass.

According to an interview with the Huffington Post, Lisa Corrin–the Block’s Director and one of the show’s curators–became fascinated with Moorman after seeing a photograph of the cellist performing Nam June Paik’s TV Cello. On view at the Grey, the electrifying photograph sparked Corrin’s interest even though the piece was credited solely to Paik.

This sheds some light onto Moorman’s extensive absence from art history’s ivory towers and institutional spaces. Similar to most classical musicians, her scores were often created by other artists. Some of these pieces were written for her specifically, as seen in her longtime collaboration with Paik. Others, she appropriated, adding her own personal flavor (occasionally to the artist’s dismay like John Cage who grumpily referred to his own 26ʹ1.1499ʺ for a String Player as “the one Charlotte Moorman has been murdering all along”).

Peter Moore, Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik performing John Cage’s 26ʹ1.1499ʺ for a String Player (Human

Cello section), Café au Go Go, New York City, October 4, 1965, Gelatin silver print, printed by Laure Leber, 1999, Courtesy Barbara Moore and the Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Photograph © Barbara Moore/Licensed by VAGA, NY

Because of this, Moorman has often been treated like a passive–and attractive–female body mindlessly performing the works of male geniuses. And if you think this has changed in the more socially conscious and diverse art world of the 21st century, just search for Moorman’s name in the Museum of Modern Art’s online collection database. You’re sent to a page on Nam June Paik.

Refreshingly, A Feast of Astonishments works hard to emphasize Moorman’s unique artistic vision and influential interpretations of others’ performances. This is accomplished through sheer staggering numbers of works alone. The checklist that the Grey Art Gallery sent to me extends to an eye-popping 108 pages long.

Charlotte Moorman performing Jim McWilliams’s Sky Kiss, Sydney Opera House, Sydney, Australia, April 11, 1976, Unidentified photographer, reproduced courtesy of Kaldor Public Art Projects

One benefit to this comprehensive and overstuffed exhibition design is that the diversity and scale of Moorman’s daring and challenging performances completely surround viewers. There’s a video of Moorman dragging her bow across Jerry Lewis’ back on The Merv Griffin Show in one corner. On another wall, she plays the cello in Jim McWilliams’ The Ultimate Easter Bunny (Candy) while covered in chocolate and coconut flakes like an Easter egg hunt gone wrong. Whether floating above the audience’s head attached to balloons or playing a giant cello made of ice, she seems willing to do just about anything for experimental art. Moorman becomes the unapologetic feminist role model that we never knew we needed.

This doesn’t mean that the exhibition remains as fresh and energized the whole way through. Grey Art Gallery’s basement space devoted to the Annual Avant Garde Festival suffers from information overload with numerous photos, videos and ephemera on work by her artist peers. It feels like a diversion even if she did organize it. If this wasn’t enough, there’s a second Moorman-centric exhibition Don’t Throw Anything Out, focusing on her personal archives, at Fales Library & Special Collections. Taken alone, the intimate show might hold real interest, especially in relation to the fellow hoards in the New Museum’s The Keeper, but with the glut of everything else Moorman-related, it felt overwhelming.

The most successful parts of the already significant show occur when the archival and artistic elements come together to give Moorman a voice–both artistically and sometimes, literally. Take, for example, the corner devoted to the infamous 1967 performance of Paik’s Opera Sextronique and its subsequent controversy after Moorman was arrested for indecent exposure. True to her nickname, she had been topless during the second section after performing in a remote-controlled electric bikini in the first. Neither Moorman or Paik were able to finish the last half of the performance after being accosted by plainclothes policemen.

Thomas Tilly, Charlotte Moorman performs Aria 4 of Nam June Paik’s Opera Sextronique, Düsseldorf, West Germany, October 7, 1968, Courtesy AFORK (Archiv künstlerischer Fotografie der rheinischen Kunstszene), Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf

Producing a narrative of this, at the time, notorious story, vitrines present props from the performance including some unsettling animal masks and the electric bikini, which look like a wire-covered fire hazard. There is also a series of photographs and letters written to New York Mayor John Lindsay on behalf of Moorman by fellow artists such as Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg.

However, the most illuminating inclusion is a taped recording projected into the gallery discussing the incident in a 1982 interview. The piece is projected into the gallery, allowing her voice to resonate through the space. In it, she describes her arrest, the controversy and how she couldn’t understand what the fuss was about. With a deadpan Southern drawl, she is blunt, funny and passionate about the art’s importance. It becomes quite clear that Moorman was much more than a beautiful model for Paik’s masculine talent. With moments like this scattered throughout the exhibition, A Feast of Astonishments puts Moorman into her rightful spot in Fluxus art history as a powerful collaborator and bold avant-garde performance artist. The hope is that subsequent exhibitions on this era of performance art will follow suit.

Comments on this entry are closed.