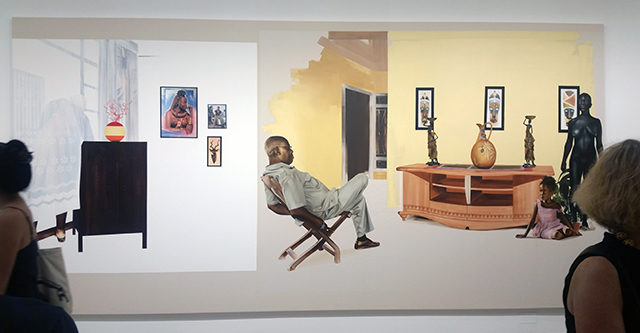

“Comrades,” 2015 three panels: oil on canvas. All images by the author unless otherwise noted.

Meleko Mokgosi: Democratic Intuition: Lerato

Jack Shainman Gallery

513 W. 20th Street

&

Meleko Mokgosi: Democratic Intuition: Comrades II

Jack Shainman Gallery

524 W. 24th Street

Both on View until October 22nd, 2016

Can a painter ever really capture the essence of a place, while considering the canvas a stage unto itself? I wonder this, among other things, when I stand in front of Meleko Mokgosi’s massive works. They’re part collaged index of postcolonial concerns, day-to-day southern African life, images-within-images, disjointed architectures, globally hybridized art history lessons, and domestic mise-en-scène. They feel politically urgent, but move slowly, happy to meander across the border into the realm of magical realism.

Mokgosi’s sprawling, ongoing body of work Democratic Intuition includes two new chapters, presently installed at both of Jack Shainman’s Chelsea locations. On 20th Street Lerato, which almost-but-not-quite translates to “love*” in the artist’s native Setswana, art-historicizes contemporary life in postcolonial southern Africa with somewhat esoteric references and allegories. Meanwhile on 24th Street, Comrades II frames the ongoing process of African liberation from a Marxist perspective, using enormous oil paintings of school photos and text bleached directly into raw canvas, among other imagery.

This paraphrased press-release introduction might read like it’s describing a painfully heady or overly didactic exhibition, but I can’t think of another show on view in New York this Fall that elicits such visceral subjective responses. Mokgosi’s work is more a restrained celebration of figurative painting’s unmatched capacity for empathy than a pure civics lesson. This might be due to the fact that, like most of the crowds in Chelsea, I can’t read Setswana and there’s no English transcription of the lengthy blocks of barely-legible printed text (referred to as dinaane, ever-changing oral histories). Mokgosi states that he’s opposed to translation, as it’s an imprecise science. But a truly great storyteller doesn’t need subtitles, and Mokgosi’s cinemagraphic sensibilities lend themselves to paintings that feel less like documentaries and more like an addictive telenovela from an uncommonly skilled director.

“Democratic Intuition, Lex I,” 2016 oil and pigment transfer on canvas.

The monumental canvas “Democratic Intuition, Lex I” in Comrades II for example, must be actively watched rather than passively viewed. At first glance, the composition is deceptively sparse. The eyes are drawn to a bronze-black figure with cadmium red lips, a statue floating over young girl. The girl is shooting an incredulous look across the room, potentially at a man (her father?) who is turned away from the viewer. Perhaps he’s watching the girl or the statue, whose own gaze is cast over the heads of the audience, as if she’s keeping watch on the horizon. The decor suggests a middle-class African residence, and behind the man’s head individual pictures or design objects are each rendered differently against a crisp white background. It’s a seductive smorgasbord of painting styles, surfaces, sightlines, and visual textures. None clash thanks to the capacious breathing room afforded by expansive negative spaces.

“Democratic Intuition, Lex I,” 2016 (detail).

This negative space feels carefully considered and dreamy. I originally thought a whole other composition had been edited out of the frame with a layer of white paint. Then came the realization—there’s more to the scene. A figure is hunched in front of a window. That transparent white wash is actually a carefully rendered backlit curtain. Is she a maid cleaning? The child’s mother? The man’s wife? Someone wholly unrelated to the other domestic scene? Her back is turned to us, and perhaps the little girl has been casting her furtive stare to the woman’s task all along.

If Michel Foucault could devote page after page dissecting the panopticon-like awareness of gaze in Velázquez’s “Las Meninas” as a turning point in Western art and class-consciousness, the contemporary Western critic must accept and enjoy a bit of futility in such an excavation of Mokgosi’s work. That’s not to say these scenes aren’t politically loaded—equally documentarian and theatrically, carefully composed. But we get the sense that we shouldn’t expect to know the whole story. The translucent curtain between the viewer and the figure with her back to us becomes the most telling device here—we’re given just enough information to have our curiosities piqued.

In the context of an exhibition with Marxist overtones, that curiosity functions as an uncommon but highly effective gateway for empathy. The viewer is seduced into these immersive tableaus, wherein the characters never feel like demonstrative archetypes of their respective socioeconomic classes, but individuals with suggested—but ultimately unknowable—identities. From the exhibition text:

“Democratic Intuition as a whole poses questions about how one can approach ideas of the democratic, founded on the simultaneous recognition of alterity and ipseity, in relation to the daily-lived experiences of the subjects that occupy southern Africa. The project focuses on the ways in which democracy is something that is inscribed within the individual from various institutions and how without access to the knowledge of how to use the state and its apparatuses, a subject can forgo claims to democracy. Together, these chapters seek to uncover the manner in which individuals invest intense emotional energy into others and objects and how these investments play out in relation to the democratic.”

Opposite “Democratic Intuition, Lex I,” the three-panel painting “Comrades” mashes-up disparate indoor/outdoor scenes—from a suited man in conversation on a porch to colorful interior. The architectural spaces almost blend together, as details or whole forms dissolve into blank canvas or taper off at the adjoining edges. The strategy recalls the first iteration of Democratic Intuition I had the pleasure of seeing at the ICA Boston. There, individual canvases were hung end-to-end, creating a wholly surround mural that seemed to reference sequential painting’s origins as a form of protocinema married to architecture and place (narrative frescos, so forth). The images had been sourced from found photos, such as newspaper clippings, that depicted Botswana while Mokgosi was living and working in New York. I was struck by how passionately these collaged, enlarged, and lovingly painted scenes spoke to a sense of place—one defined by snippets of often-incongruous moments rather than a coherent overarching story.

“Democratic Intuition, Lerato: Agape II,” 2016 oil on canvas 84 x 56 inches (L) and “Democratic Intuition, Lerato: Xenia,” 2016 oil on canvas 90 x 179 1/4 inches (R). Image courtesy of the gallery.

“Democratic Intuition, Lerato: Agape II,” 2016 oil on canvas 84 x 56 inches (L) and “Democratic Intuition, Lerato: Xenia,” 2016 oil on canvas 90 x 179 1/4 inches (R). Image courtesy of the gallery.

So I was at first a little disappointed when I walked into Democratic Intuition: Lerato. The paintings here, though mostly plus-sized, are generally hung far from each other, each to be considered as a singular precious art object within its own distinct picture plane. Only a few of them are as immediately “penetrable” as the more installation-like presentation—a memorable pleasure I had looked forward to repeating. But the logic behind this series has its own rewards—many of the works here were inspired by compositions from 19th Century academic painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau, who painted classical mythology, campaigned to open France’s art institutions to female artists, and ultimately fell out of favor as newer styles such as impressionism rendered his romantic classicism “obsolete.” For a series about love, democracy, and the enduring near-universal appeal of figurative painting, it’s a wise allusion.

“Democratic Intuition, Lerato: Agape II,” recalls the Bouguereau painting “The Assault,” in which a hesitant woman is swarmed by Cupid-like cherubs (all of the above Caucasian). In Mokgosi’s rendition, the woman is Black, surrounded by White cherubs. She looks vaguely irritated, and the pastoral foliage of the original painting has been reduced to a few broad strokes of decadent/sickly-looking cadmium green. It’s both a gorgeous oil painting and a somewhat funny allegory for the mess wrought by colonialism.

“Democratic Intuition, Lerato: Philia II,” 2016, oil on canvas tondo, 94 inches diameter.

But the two show-stoppers in the 20th street space couldn’t be more different from one another. “Democratic Intuition, Lerato: Philia II” is an absolutely stunning piece of portraiture. The central figure is framed by a postmodern shelving system that’s dry brushed and evokes a Renaissance composition sketch. In the shadows, the silhouette of a maid leans with a posture that seems calculated to express difference from the formally-posed women and even dog in the foreground. No angle seems arbitrary, down to details such as the actually-metallic gold picture frames on the shelf. The whole painting immediately conjures a domestic drama to rival Dynasty—this sitter exudes confident power and a desire to keep it.

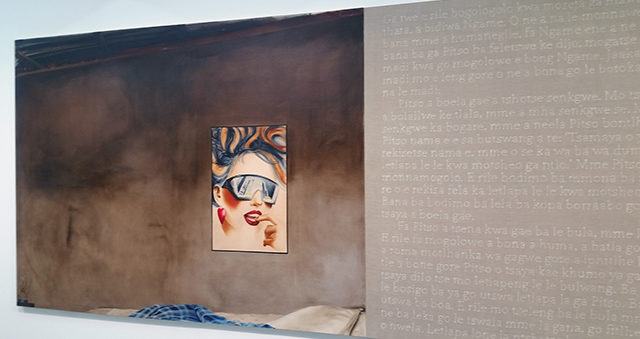

“Democratic Intuition, Lerato: Familia II,” 2016 two panels: oil on canvas, bleach on portrait linen

Conversely, “Democratic Intuition, Lerato: Familia II” is washed in an uncharacteristically muddy palette. One half of the diptych is an oddly cropped peek into a humble bedroom, where the bottom of the frame holds an unmade bed and oil-burning lamp. The other panel is another bleach-on-linen dinaane. I couldn’t read the story, but unlike most of the work in Democratic Intuition, the composition has a lonely suggestion of absence. It’s the polar opposite household from the one depicted in “Philia II,” save for one “aspirational” piece of decor. In what is an apparently 1980’s poster, a Western-looking woman is a beacon of anachronistic glamour—an exotic contrast to the dingy setting. In her mirrored sunglasses, we catch a glimpse of a cosmopolitan skyline—a little piece of Manhattan reflected back from across the ocean, returning our gaze as spectators.

Comments on this entry are closed.