Installation view

Dieter Meier

Possible Beings 1973-2016

Galerie Judin, Berlin

Until October 29, 2016

What becomes a near-legend best? A fresh new mantle of re-invention. Plus a few bitter truths held up to the baldest light.

Dieter Meier, best known outside of Europe as one half of the influential electro-pop band Yello, works in photography, video, and performance. His latest exhibition echoes a project he first began way back in 1973. In his youth, Meirer decided that he wanted to be other people. He created a set of new identities, named each and wrote back-stories for them, and then crafted photographic self-portraits of the various iterations. Some were writers, some were filmmakers, some physicists and some acrobats. So far, so Suzy Lake, Cindy Sherman, General Idea, Gilbert & George, Bruce Nauman, Rebecca Belmore, etc., etc., etc.

Like no end of artists from the Baby Boom generation, and, arguably, a truckload of those following, Meirer played clever identity games mediated through his era’s available and fashionable technologies. The games centered on the unreliability of identity as the core impulse of his practice. Meirer is a profoundly 20th century artist, as his preoccupations with the self and self-presentation proves.

The reason for the “2016” in the subtitle is Meirer’s decision, in the last year, to revisit his characters from 1973 and give each an updated, self-portrait (or perhaps more accurately “self-portrait enactments”?). I use the term character as opposed to persona intentionally. These new works are not deep enough to be labelled as revisits to previous personas; they lack gravitas, nor do they carry the same weighted performativity. They are lighter in heart and tone, at times even silly. Furthermore, it is arguable that each individual portrait is a character and that collectively the multiplicity of characters is the persona in Meirer’s show and tell.

What Meirer is not doing is re-opening a can of long-dead dissociative identity disorder worms from his past, and not re-playing the old game of self-fracturing. Rather, he is investigating his present, and one cannot help but come away from this exhibition with the bitter sweet realization that alongside the obvious role playing, the project is embedded, by its very construction of a then vs. now, with meditations on the ravages and rewards of aging. Unease and uncertainty haunt this exhibition, and I loved it for that. Getting older, as Bette Davis legendarily noted, is not for sissies.

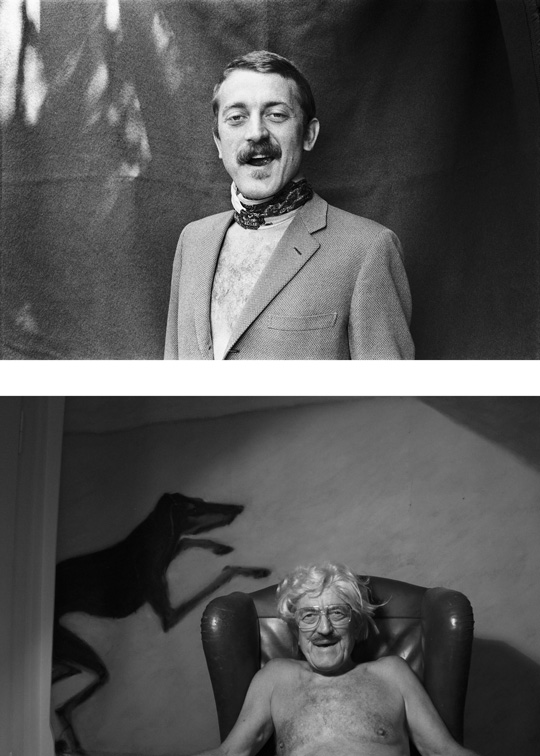

The 1973 Meirer(s) sported curling, voluminous locks, a moustache you could lose your keys in, and dreamy fuck-me eyes. The 2016 versions of the same characters appear vibrant and healthy (for their age, an important proviso), but also fragile, even broken. The hair is still there, but it looks washed out and stringy. The moustache appears parked on the face more than an integral part of the overall look, and many of the Meirer(s) wear glasses.

The natural glamour of the 1973 photos, all depicting young men about town in their first blush of vigour, changes to a constructed glamour – the men lean seductively against walls, wear open, unbuttoned shirts or no shirts, and appear in front of assembled furnishings that mark their achieved statuses. Looking at these older men, I could not help but be reminded of the kinds of self-positionings I see all the time on gay hookup sites, where men well into my age range (I am 51) and beyond pose and dress in manners suggesting that they are much younger than whatever age simple chronology has perversely imposed on their still strutting selves.

Samuel “Samy” Schnyder | from Possible Beings | 1973–2016 | Inkjet on baryta paper, mounted on aluminum | 40 × 60 cm | Edition of 3 + 2 APs

I know that sounds bitchy, but I don’t mean it that way. What fascinates me about “Possible Beings” is its unflinching look at how masculinity is burdensomely trope-laden. All of the 1973 works make the characters’/Meirer’s maleness of first importance, either in a sexualized, shirtless-and-available fashion, or via farcically gendering facial hair/clothing signifiers. Cue Judith Butler. The 2016 series subsequently lays horribly bare how artificial (and thus easily thwarted) the idea/ideal of the male remains today.

The 2016 characters’ self-portraits convey a subtle anxiety over cultural relevance – the characters employ prop status markers such as cars and athletic gear – and, more toxically, male potency. The grinning characters want us to know they are still in the game, on all levels, still men to be reckoned with and/or seduced by, still sexy, still capable. Most telling, they are also still very much uncomfortable with their projected image, decades later. The sprightly, young but uncertain 1973 gang has morphed into an aging and wary old boys club that’s still fronting .

As much as this exhibition is about the onion peeling we call identity construction, the relentless game of self hide and self seek, it is also a bristling, and I would argue at times merciless, mockery of the many half-truths and flawed gender scripts that propelled the so-called Me Generation—now wilting flower children. There is no fraud, Meirer shows, like an old fraud.

Comments on this entry are closed.