A.L. Steiner, 30 Days Of Mo:)rning, 2016, color pigment prints and photocopies (photo by author)

A.L. Steiner: 30 Days of Mo:)rning

Koenig & Clinton

459 West 19th Street

New York, NY

On view until October 29, 2016

What a difference two weeks make. I was ready to write-off A.L. Steiner’s current exhibition 30 Days of Mo:)rning at Koenig & Clinton as an overly ambitious mess after my initial visit. But on second viewing, the show, which Steiner adds to daily, presents an effective elegy to our seemingly doomed contemporary society.

Much of the success of Steiner’s exhibition has to do with its thematic relevancy. With the looming presidential election, existential dread seems quite timely. But what feels so refreshing about her engagement with the copious issues facing us in 2016, is that she does so without once referencing Donald Trump. The problems she takes aim–capitalism, climate change or the patriarchy–are larger than a singular election or even, one country.

30 Days of Mo:)rning alters almost everything about gallery business as usual. The first thing viewers will notice even before stepping into the gallery is the sheer difficulty of finding the time to see it. Throughout its 30-day stint, the gallery is only open four hours a day from 12PM to 4PM.

A.L. Steiner, installation view of 30 Days of Mo:)rning at Koenig & Clinton (Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, New York)

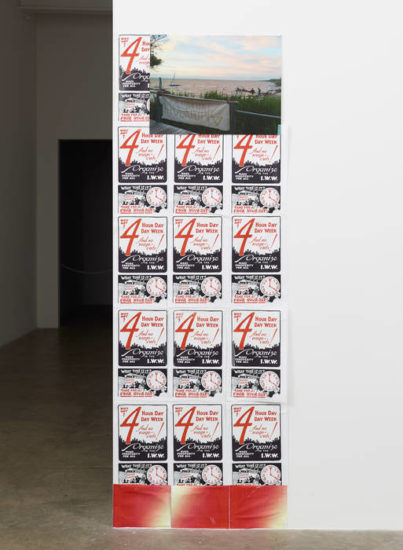

This hourly restriction is more than just a way of pleasing overworked gallerinas. A work in the entrance of the gallery provides some insight into the historical motivation behind Steiner’s reduction of gallery hours. Untitled (Mo:)rning) features three columns of vintage-style posters from the Industrial Workers of the World (I.W.W.), a long-running labor union, calling for a four-hour work day. While the union offered this four-hour day as a solution to unemployment, Steiner seems to see it as a way to throw a wrench into the capitalistic drive of a Chelsea gallery.

Her destabilization of gallery convention doesn’t end there. She adds new photographs to several of her collaged assemblages each day, thus keeping the show in a state of constant flux. She also reads a new selection of text daily in the gallery. Both times I saw the show, though, Steiner wasn’t there, so all I saw was her bare table and a chair in a corner.

Even without Steiner’s physical presence, the continual reimagining of the exhibition allows viewers to have a different understanding of the show depending on what day they visit. And if my experience is any indication, this can vary widely.

Segment of A.L. Steiner’s Welcome to the Misanthropocene (in 30 sections), 2016 (photo by author)

On first viewing, the exhibition looked haphazard. Certain walls featured crowded groupings of photographs while others remained bare. It looked like the art handlers went on strike mid-installation. But, yesterday, Steiner’s critical–and political–vision was better articulated with two more weeks of materials on the walls. Rather than a manic, everything-goes hanging style, the newer materials were hung quite conventionally, which balanced some of the more congested walls at the front of the gallery.

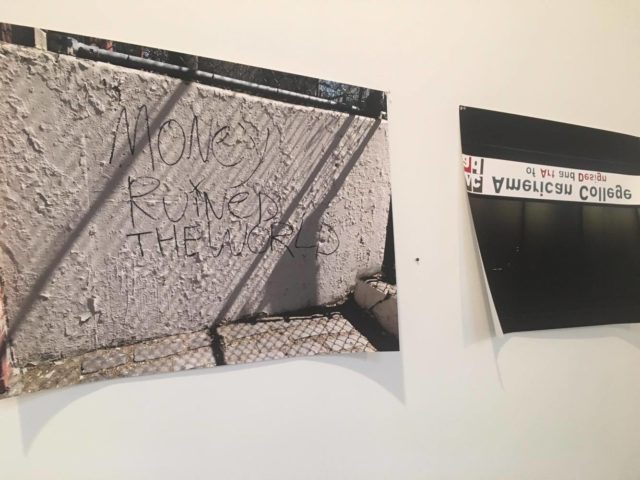

Overall, 30 Days of Mo:)rning feels apocalyptic. Between photographs of graffiti that say “Money Ruined the World,” a woman with her head down in a fast food restaurant and a tree growing in a pot planter filled with trash, it looks like we’re all screwed. Even her photographs of natural scenes like sunsets and beaches have a certain ominous quality. I read this as a warning to viewers: enjoy these environments while they last.

Detail of A.L. Steiner’s War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength., 2016 (photo by author)

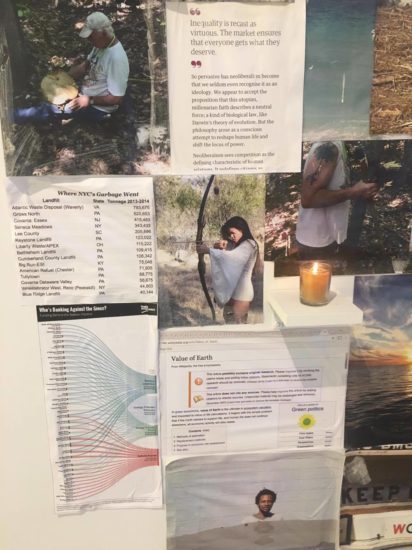

Take, for example, War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength, which is an overlapping grouping of images on a freestanding wall in the front of the gallery. The work contains idealistic images of waterfalls and sunsets interspersed with screengrabs of articles and images. I saw a Guardian article with the headline,“ExxonMobil CEO: Ending oil production ‘not acceptable for humanity’,” a graphic on “Where NYC’s Garbage Went” and scientific images of our warming oceans. Photographs of activists holding signs that say “We are water,” were peppered in as well.

Looking at all the images together, the work reflects of the threat to our civilization by our civilization. This isn’t a criticism of one political party or another, but an entire capitalist system that destroys the environment for profit. With a candle sitting in front of the collage of photographs, the piece becomes a moving tribute to our diminishing environmental resources.

Section of A.L. Steiner’s Welcome to the Misanthropocene (in 30 sections), 2016 (photo by author)

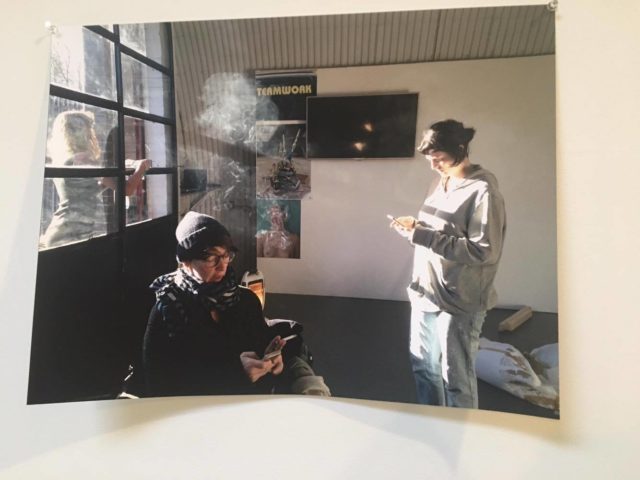

The exhibition would be a total downer were it not for Steiner’s use of bodies–often queer bodies–as symbols of hope and possibility. For example, the ongoing Welcome to the Misanthropocene (in 30 sections) juxtaposes screenshots of Google searches like “90% of killers are male,” with photographs of queer men in speedos on a beach or women sitting, playing on their phones and talking in, what looks like, an art space. While representing fairly mundane moments, these photographs convey sense of community in the face of an exhibition of mostly doomed prospects.

As a whole, 30 Days of Mo:)rning is a protest–even without an easily digestible slogan or set of demands. Rather than setting her sights on one issue (real estate, misogyny, Wall Street, etc.), which many shows have done previously, Steiner mourns it all. By altering gallery production and forcing these issues within a white-walled gallery space, Steiner conveys a refusal to willfully sit aside, and create apolitical art in the wake of all these insurmountable problems. And like any effective protest, she makes us confront them as well.

Comments on this entry are closed.