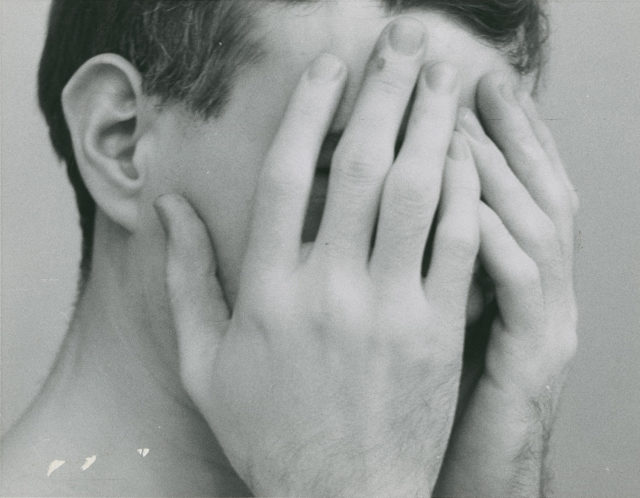

Edward Wallowitch, Andy Warhol with Face in Hands, 1957–58, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (© Estate of Edward Wallowitch. All rights reserved)

Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body

Andy Warhol Museum

117 Sandusky Street

Pittsburgh, PA

On view until January 22, 2017

It’s hard to imagine there’s anything new to say about Andy Warhol. The glut of books, articles, dissertations and exhibitions on the artist seems to always tread the same critical territory–celebrity, consumerism, “business art” and mass production. But, Associate Curator Jessica Beck found a refreshingly innovative take on the much-analyzed artist in her current exhibition Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body at the Andy Warhol Museum.

The show examines Warhol’s treatment of the body–a subject, which Beck says has been woefully overlooked by curators and historians. “Everyone thinks it’s just understood. Somehow it keeps missing its place in the exhibition history,” Beck explains. This oversight is the driving force behind the exhibition, which thematically traces Warhol’s figural interest through his career.

Like Warhol himself, the body, as a subject in art, is so widespread that it’s almost cliché. Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body goes beyond simplistic analysis to tie his artistic employment of the body with his fraught relationship with his own body and sexuality. As seen in the introductory wall of photographs of Warhol that shows the artist both exposing and concealing his body, Warhol’s struggle with his physicality reflects the tension between perfection and imperfection in his art. This not only encourages viewers to take a second look at Warhol’s often familiar work, but it humanizes an artist that–partially by his own design–became a caricature.

Curious to learn more about the organization, I spoke with Jessica Beck about the inspiration behind the exhibition, Warhol’s own “perfect body” and why the exhibition feels so timely.

What inspired you to delve into Warhol’s use of the body?

The earliest thing that got me looking into Warhol and the body was thinking about his late Last Supper paintings, namely his treatment of Christ and how it speaks so directly to these larger ideas that have been laid out by Renaissance historians about the sexuality of Christ. Leo Steinberg wrote a really important and highly criticized book [The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion] about the sexuality of Christ. It delves into the idea of “normal” in the Catholic Church–what was acceptable and what wasn’t–not only in terms of the imagery, but in society. I started thinking about Warhol, what was acceptable for him, how that got manifested in the work and what work became popular. For example, when you look at the catalogue raisonné, the beginning period has all these fascinating paintings from 1961 that no one really pays attention to. Everyone skips them because they want the Pop story. They go directly to the comic strips, the Campbell Soup cans and the Coca Cola paintings because those relate directly to the narrative of class, consumerism and the rise of American culture. What comes before that, though, is a very serious investigation of his sexuality, the body, beauty and what it means to be a painter. He’s exploring how to paint with these symbolic images of a nose job in Before & After. It’s very difficult to look at that painting and not think of many things–not only of beauty and transformation, but Warhol’s own nose job and the idea of assimilating as an immigrant by transforming your bulbous, ethnic nose to fit in. He’s figuring out how to be a painter and figuring out his message.

Andy Warhol, Before and After, 4, 1962, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from Charles Simon © 2016 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Digital Image © Whitney Museum, N.Y.

In the exhibition catalogue, you interview theorist and historian Douglas Crimp who points to homophobia as a reason why Warhol’s body and queerness is sometimes underrepresented. But it also seems like art historians are so driven to contextualize these works within a commercial or celebrity model that they ignore what is right in front of them–the body. Why do you think this aspect of Warhol’s work has been ignored for so long?

I think some of it is that a lot of this work wasn’t exhibited during Warhol’s lifetime. Because of that, it didn’t get put into the narrative. The way it’s been treated–and don’t get me wrong, the early paintings from 1961 are prized paintings–but they’ve been treated as one-off ideas as opposed to the real beginning of his work.

You mentioned Warhol’s own nose job–what influenced your decision to not only look at the treatment of the body in Warhol’s work itself, but his life?

Going back to the original idea of the religious body, there is this push and pull between concealing and flaunting. I thought about the work and Warhol’s own journey with that tension in his own image. He was so intentional about the way he was photographed. He ends up being a different artist than someone like Jasper Johns who you rarely see a photograph of other than in the studio. Warhol paid particular attention to his own image. I wanted that self-fashioning to be a part of the show and that beginning wall demonstrates that.

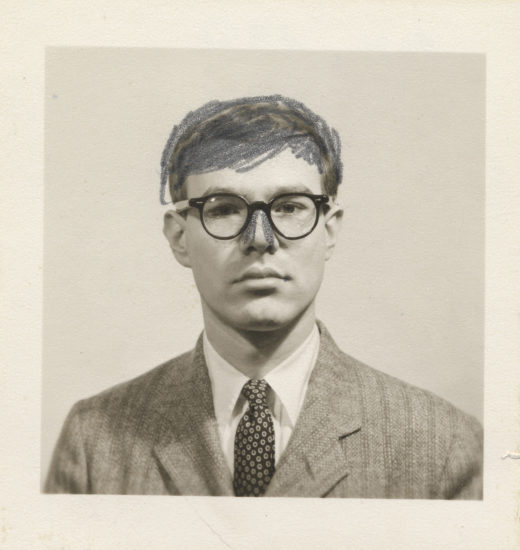

Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait (Passport Photograph with Altered Nose), 1956, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Warhol was publicly very self-conscious of his body and face, frequently writing about his dislike of his skin and nose. This makes the title My Perfect Body seem rather jarring. Where did the title come from?

This is something I thought a lot about. I tried a few other ideas, but I loved the almost irony of it. I landed on it because it’s something that you think of with Warhol and beauty–this idea of attaining the perfection that you see in commercial advertising. It’s an unattainable perfection. In a way, it’s almost as if Warhol’s own image functioned in that world of unattainable perfection. His own image and his way of living would never be completely what he wanted. There’s a tension in the title too. You think, “I don’t think of Warhol having a perfect body.” But John Giorno, in the catalogue, writes an essay about how Warhol, in fact, had an Adonis-like, beautiful figure, which feels untrue but maybe it’s not. The essence of the entire show is to think about Warhol differently so I wanted the title that would make viewers to say, “What?”

A theme that becomes clear throughout the show is Warhol’s representation of gender. In the 1950’s, his figural drawings of men are quite feminine, his Marilyn Monroe is almost a drag queen and his nudes seem androgynous. There’s a gender fluidity in almost every work with the exception of the figure of the body builder, which looms large in the show. How does the body builder fit into Warhol’s treatment of masculinity and gender identity?

I think, for sure, there are moments of androgyny going on in the work. The female genitalia in a painting called Shaved Vagina feels almost questionable for a moment. You’re not really sure what you’re looking at. But with the body builder, there’s a trying on of masculinity or a performing masculinity that comes out. It’s an extreme exaggeration of an ideal. There’s also a definitive desire element going on, which is why I wanted the film Super Boy in the show. It’s this lush, tightly cropped portrait of a completely muscular young body.

Andy Warhol, The Last Supper, 1986, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Was there anything that surprised you about Warhol’s use of the body or the organization of the show?

I think what happened with the show–and what I hope happens with the viewer–is that I started thinking about Warhol differently. Then, I started seeing the work differently. It became almost impossible not to see the work through this lens–this sophisticated look at the idea of beauty, shame and torment. What surprised me was how strong the thesis of the show was and thinking, “Oh, this is really in the work.” I’m hopeful that it leads to more writing about these ideas.

In the introduction of the catalogue, you describe the show as timely, which I’d agree with. How do you see Warhol’s treatment of the body reflected in more current contemporary art?

I see this show reflected in contemporary society. We’re living in this completely Photoshop-ed world. Even Instagram is an instantaneous version of the Polaroid, which can be doctored with a filter, enlarged and posted for the world to see. Warhol was working in an analogue fashion to create that Instagram filter with those bright lights for his portraits.

I’m not sure I can pinpoint exact contemporary artists, but right now, we’re living in a fascinating moment when we’re embracing ideas of androgyny. We’re figuring out how to talk about the body, gender and what it means to be feminine or masculine–these ideas that were very theoretical in Warhol’s work. Now society is changing. Part of the journey with Warhol and the body is that there was a lot of rejection of him. A lot of that rejection was founded on his sexuality and how he wore his sexuality. Now, it’s becoming more and more acceptable to wear your sexuality in a way.

Comments on this entry are closed.