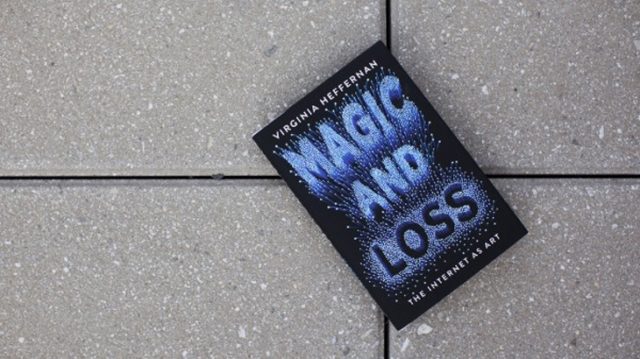

Promo image for Virginia Heffernan’s lecture at SVA last Tuesday (image visa sva.edu)

Virginia Heffernan joined the Internet in 1979 at 9. Growing up near Dartmouth, the cultural critic learned the computer language BASIC from the college’s president John Kemeny with a group of her classmates. I learned this random factoid about Heffernan’s online life at her lecture last Tuesday night at School of Visual Art’s Design Research, Writing and Criticism Department, where she discussed her new book Magic and Loss: The Internet As Art.

Heffernan’s bizarre, meandering lecture was full of tidbits about her own web usage including her high score in Angry Birds, her meetings with Google or her chat room experiences on early live chat feature Conference XYZ. Her over-the-top adoration of her own online history might explain why she thinks the Internet is art.

Not just any art, but a “massive and collaborative work of realist art,” as she writes in Magic and Loss. Despite this quote–and the title of her book, Heffernan couldn’t seem to decide on Tuesday night whether the Internet was art or a game (or some weird amalgamation of the two).

After her childhood introduction to BASIC, Heffernan didn’t eventually “work at NASA” as her parents were promised. She fell headfirst in love with online chat culture through Conference XYZ. The experience of creating her first avatar “Athena” on Conference XYZ still influences her perception of the Internet today, namely its use for “character creation.” Recalling how Conference XYZ helped her “find her way socially,” she described the chat room as a “crash course in this cultural way of talking.”

Remembering her mother’s commands to stop “playing” with the computer when she tied up the phone lines with Conference XYZ, she admitted that she can’t quite shake the notion of using the Internet as playing. This led her to theorize in Magic and Loss that the Internet is “a massively multiplayer online role-playing game.” And she’s not wrong. All of our tweets, Facebook posts, Instagrams, emails, comments, reaction GIFs and even, blog posts can easily be regarded as a form of role-playing. The Internet is just a game disguised as reality.

Fuck you, Anthony Wiener.

— Virginia Heffernan (@page88) October 30, 2016

Illuminating this idea of online life as a false representation of reality, Heffernan recalled a recent tweet she sent, reading “Fuck you, Anthony Wiener [sic].” She explained she would never actually say that aloud in public, but her Twitter “avatar” @page88 is bolder and more confrontational. “I also don’t talk in 140 characters,” she pointed out. By understanding all social media profiles as “avatars,” she shatters the myth that somehow these online personas are truthful representations of ourselves. Instead, they are just a character created to maneuver through a constructed game with set rules and restrictions.

But, a game isn’t necessarily art. Granted, it’s not a simple task to definitively declare an object as art. The definition of art, at least for me, is amorphous, ever-changing and often, dependent on the creator’s intent. Of course, artists have used the Internet as a medium since the earliest days of net art. But, understanding the vast noise of the web itself as art feels like a stretch. In fact, I shudder to imagine sites like reddit or Breitbart News as part of one gigantic art piece–or a game.

For Heffernan, art seems to boil down to merely having an aesthetic. Returning to her initial adoration of Conference XYZ, she described at length how “that interface stayed with me–the green letters on the black background.” With this interface, she learned that “letters can be moving and positive.” The seemingly limitless interfaces like Conference XYZ led her to question, “What is the relation to this deep mystery?”

She appeared to mourn the loss of this messier vintage online aesthetic. Several times in the lecture, she compared the “inelegance of the web” to the cleanliness of apps, which she finds akin to the creepily perfect architecture Levittown. Even though she describes the web’s aesthetic “as if modernism never existed,” she sees the power in the unexpected juxtapositions that happen online with its layers of ads, banners, texts, video and images.

Heffernan strangely seemed to counter her own argument about the Internet’s aesthetics as proof of its definition as art in her conclusion. She finished her lecture by quoting a passage from the first chapter in Magic and Loss on design. In the chapter, she delves into the intended effect of the attention-grabbing graphics that epitomize the Internet’s look. She read, “the graphic artifacts of the Web civilization don’t act like art. They act like games….Rather than leave you to kick back and surf in peace, like a museum goer or a flaneur or a reader, the Web interface is baited at every turn to get you to bite.”

If these online artifacts act like a game rather than art, then why should we, like her book and lecture assert, consider the Internet art? I didn’t find a successful answer through Heffernan’s scattered lecture. Instead, she described our interaction with the Internet by randomly evoking a line from a 800-year old Chinese poem (which also gives Chinese search engine Baidu its name): “the search for retreating beauty amid chaotic glamour.”

Comments on this entry are closed.