Carrie Mae Weems, All the Boys (Profile 2), 2016, archival pigment print (©Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

Carrie Mae Weems

Jack Shainman Gallery

513 West 20th Street and 524 West 24th Street

New York, NY

On view until December 10, 2016

I often hear the platitude that art thrives when artists are forced into action by life or death necessity. But, what might this new politically engaged art actually do to combat racism, xenophobia, misogyny and a host of other threats that have already appeared well before Trump’s inauguration?

Carrie Mae Weems’s two current exhibitions, on view at both Jack Shainman galleries, seem to offer an answer: art can act as a witness. In the dual shows, Weems shines a light on violence, institutional silence, judicial ignorance and black underrepresentation. This is seen most vividly her gut-wrenching take on the killings of unarmed black men and women by police in the 24th street space. Not all the pieces in Weems’s shows force viewers to witness these crimes, but those that do drag these issues into view for a Chelsea art audience, rendering a passive and apolitical viewing experience almost impossible.

Weems is no stranger to this tactic. She has devoted her career to exposing the various, problematic ways people of color, namely black women, have been represented in the past and present. But, here, Weems’s artistic commentary seems more biting. Rather than wider theoretical and historical problems, she set her sights on crucial topics ripped from the headlines and popular culture.

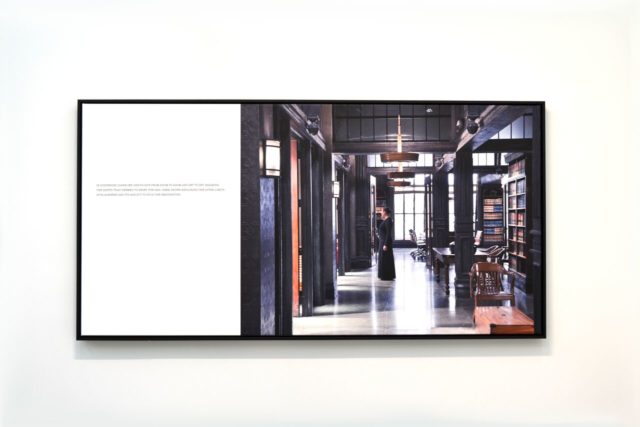

Carrie Mae Weems, Scenes & Take (In Suspended Disbelief), 2016, inkjet print on canvas (©Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

Weems’s 20th Street exhibition is a fairly conventional survey of recent work, bringing together two photographic series and a video installation. While Blue Notes, a series placing large colored rectangles on blue-toned, faded images of personas like Basquiat and Warhol, and the ghostly video installation Lincoln, Lonnie and Me are visually compelling, they didn’t feel fresh (possibly because this is the third time I’ve seen Lincoln, Lonnie and Me). Her show gained increased focus and relevancy when she turned her sights on the representation of black women in Hollywood in her new photographic series Scenes & Take.

These photographs depict Weems from behind, dressed in a glamorous gown, wandering through sets of popular television shows such as Empire, Scandal and How To Get Away With Murder. Weems has donned this black-clad muse personae before, namely in her ongoing Roaming and Museums series. While, in these series, she placed her black female body into spaces, like museums, where black women have historically been underrepresented, Weems, in Scenes & Take, celebrates the renaissance of television shows with strong black lead characters by black creators like Shonda Rhimes and Lee Daniels.

This can be seen in the text flanking the left side of each photograph, resembling a pseudo-film script. Take, for example, Scenes & Take (In Suspended Disbelief), which reads, “In suspended disbelief, she floats from room to room and set to set, marking the shifts that seemed to reset the bar–hmmm…shows exploring the outer limits of blackness and its ability to hold the imagination.” I think Weems is a fan.

Carrie Mae Weems, Scenes & Take (Director’s Cut), 2016, inkjet print on canvas (©Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

This praise for these new television shows doesn’t mean, though, she doesn’t also ask us to be critical. In particular, the work Scenes & Take (Directors Cut) takes aim at the lack of roles for black women in films by iconic directors like Woody Allen, the Coen Brothers and Martin Scorsese. Standing in Olivia Pope’s boardroom from Scandal, the text describes a round of comical rejections. “Nervously Allen said, ‘Are you crazy’… Frankly, Scorsese said, ‘Forget about it,’” Weems writes. While these quips are funny, tailored to each director’s work, the institutional racism and continued underrepresentation of black women are not. It made me look at the work of some of my favorite directors differently, and I’m sure I’m not alone.

This focus on Hollywood, pales in comparison to the dire nature of her exhibition on 24th street. The show opens with two memorable images of a man wearing a hoodie in a fog-filled background. In one photo, he faces forward while in the other, he’s in profile as if in a mug shot. By immediately confronting viewers with an outfit now synonymous with the murder of Trayvon Martin, Weems indicates that bearing witness means something more vital here.

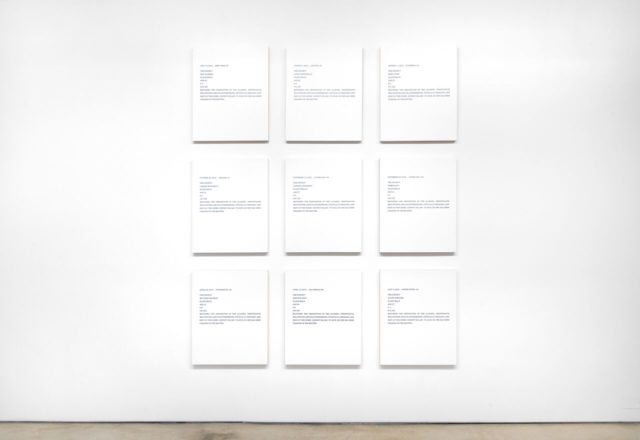

Installation view of Carrie Mae Weems, Usual Suspects, 2016, silkscreened panel (©Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

With the facts of Martin’s death–and the numerous deaths of other unarmed black men by police–so well-known, it’s sometimes hard to visualize the sheer enormity of their impact. A nearby grid of nine white text panels (with an additional tenth hung separately to the side), entitled Usual Suspects does just this, emblazoned with the names, locations, physical characteristics and death dates of the victims. The details change from panel to panel, specific to the now-household names like Eric Garner, Freddie Grey and Tamir Rice. But, one line doesn’t, which says: “Matching the description of the alleged, perpetrator was stopped and/or apprehended, physically engaged and shot at the scene. Suspect killed. To date, no one has been charged in the matter.” By presenting both the names of the ten victims and the lack of justice for their deaths directly in front of viewers, Usual Suspects feels, at once, like a memorial, a polemic and a call to action. It also reflects a cold institutional uniformity that recalls the chilling racist assumption that all these men were the same and unworthy of distinction and individual mourning.

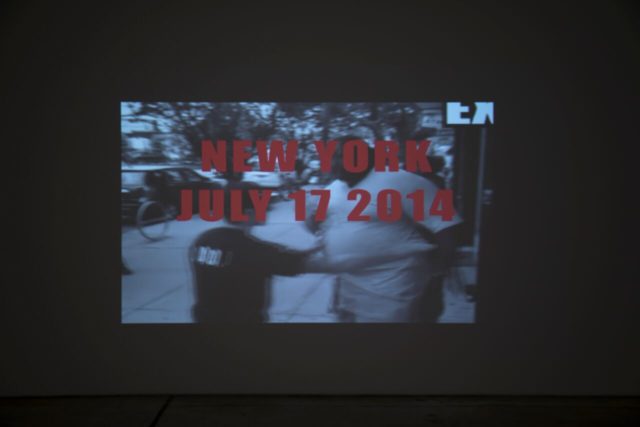

Perhaps the most successful work in the show–and the most difficult to watch–is the video All The Boys: Video In Three Parts. This fourteen-minute long video combines the cellphone footage of these men’s deaths with videos from funerals and Weems’s own dreamlike afterlife scenes. While Weems’s constructed scenes, which feature her own poetic voiceover and a man running on a treadmill in a surreal purgatory filled with clocks and a bare tree, are elegiac and mediative, they just can’t compete with the physical terror of the real videos. In one part, the screen fades to black with just the voice of Diamond Reynolds, Philando Castile’s fiancé, saying, “Please don’t tell me my boyfriend just went like that.”

Installation view of Carrie Mae Weems, All the Boys: Video in Three Parts, 2016 (©Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

At first, I questioned the ethics of using real deaths in an artwork. While these tapes have been played repeatedly on the news, seeing them one right after another in Weems’s video was beyond upsetting. It felt garish to watch these people killed while sitting in a Chelsea gallery–the epitome of privilege.

And yet, with more consideration, the video forcefully places the viewer into the role of witness, potentially motivating an apolitical art viewer to act. I’ll admit I never watched some of these videos. I figured reading the news and transcripts were enough to grasp the brutality. It wasn’t. And I wasn’t the only one visibly affected by All The Boys. When I saw the video, a woman sitting next to me was crying and had to turn away from Alton Sterling’s shooting, looking at me for some support in the dark. Maybe this moment of horror is what viewers need to be pushed into political action and protest.

And it couldn’t come at a better time. With Trump’s nomination of Jeff Sessions as Attorney General, a Senator with a history of racist statements (including referring to the NAACP and ACLU as “un-American”), the possibility of police facing charges for these deaths of unarmed people of color feels even slimmer. Weems’s exhibition, though, offers a bit of populist possibility. While the offending officers may not be held accountable by our judicial system, they’ll be held accountable through art. And hopefully, they’ll also be taken to task by its viewers.

Comments on this entry are closed.