David Spriggs, Gold, 2017, yellow acrylic paint on layered sheets of transparent film, triangular gold color structure, lighting units (Photo by David Spriggs; Courtesy the artist and Wood Street Galleries)

David Spriggs and Matthijs Munnik: Permutations of Light

Wood Street Galleries

601 Wood Street

Pittsburgh, PA

On view until April 2, 2017

Before the election and the daily drama of Trump’s administration, I never fully understood just how important the current sociopolitical state is to the success of an exhibition. Of course, I was aware that timeliness could make or break a show. But, less than a month into Trump’s presidency, work that normally wouldn’t interest me in galleries I typically bypass have taken on new meaning and resonance.

The latest project to remind me of art’s dependence on its political context is David Spriggs and Matthijs Munnik’s dual exhibition Permutations of Light at Pittsburgh’s Wood Street Galleries. The show presents two large-scale immersive installations, Spriggs’s Gold and Munnik’s Citadels, on separate floors of the gallery. Concentrated on formal aspects of light, color and form, this type of experiential installation (which are often associated with Wood Street Galleries’ programming) have become so commonplace that they seem, at this point, like a crowd-pleasing cliché. But, when viewed in the context of our surreal times, Spriggs’s critique of capitalism and Munnik’s escapism feel surprisingly relevant.

On the second floor of Wood Street Galleries, located above a T-Station (Pittsburgh’s version of the subway), the first thing viewers notice about Spriggs’s Gold is its radiating opulent color. The piece consists of a monumental inverted golden pyramid. Inside, the pyramid is filled with eleven ghostly human figures that appear three-dimensional. But, walking to the side of the installation, it becomes clear these beings are painted on numerous sheets of film, which provide the illusion of a sculpture. These figures, looking like they’re captured in glass, are creepy, resembling ancient mosquitoes preserved in amber.

David Spriggs, Gold, 2017, yellow acrylic paint on layered sheets of transparent film, triangular gold color structure, lighting units (Photo by David Spriggs; Courtesy the artist and Wood Street Galleries)

Granted, on first glance, the work appears to be a rather simple exploration of the figure and color. And yet, on further consideration, Gold begins to take on more significance due to its layers of symbolism. For example, in 2017, the color gold is, perhaps unfairly, inseparable from President Trump. Looking at Spriggs’ installation’s golden glow, I couldn’t help but reflect on the president’s tacky gilded penthouse in Trump Tower.

Beyond Trump’s tasteless interior decorating, Gold’s color scheme could, on one hand, represent the capitalist dream of America as the land of golden opportunity. On the other hand, the color could also reference fool’s gold, hinting at the downside of America’s manic search for excessive wealth.

This tension is further explored in the structure of the installation itself. The figures, as well as the installation’s inverted triangular form, resembles the pediment of the New York Stock Exchange. Only here, though, the pediment is upside down and, like an inverted flag, the form of Gold seems to express distress and potential danger. The figures, like all of us, are trapped within this unending and unequal capitalist economic system constructed by Wall Street. And with Trump as the pinnacle of the American obsession with wealth, the installation poignantly reflects the United States’ troubled late capitalist state.

The relevancy of Munnik’s Citadels, in the third floor gallery, is even more unexpected since the installation is a more formal experiment with the viewer’s perception. It was also a welcome relief from Spriggs’s cautionary economic tale. This doesn’t mean Citadels was a pleasant or gentle viewing experience. Before entering the gallery, an attendant asked viewers to sign a release form, asserting that they didn’t suffer from epilepsy, heart conditions, asthma or anxiety. Those under 18 weren’t even allowed inside.

Matthijs Munnik, Citadels (Photo by Joey Kennedy; Courtesy the artist and Wood Street Galleries)

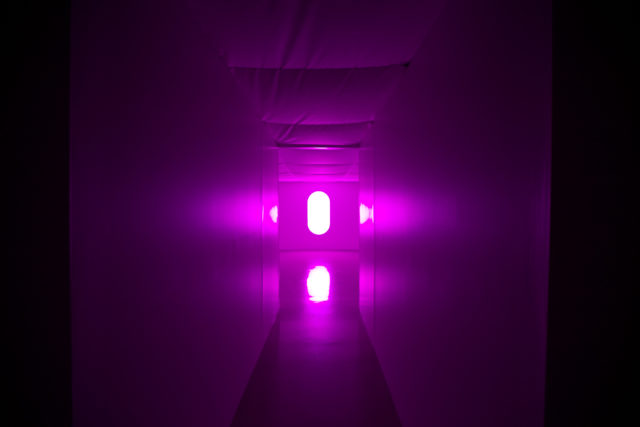

Walking down a long hallway, I immediately knew why the waiver was necessary as I began to involuntarily sweat in the strobe lights as I tried to get my bearings. Red, blue and purple lights flashed bright and fast, centering around a pill-shaped light at one end of the room. A droning soundtrack felt as though it might put viewers in a trance. And the white, tented ceiling gave an eerie sense of being in a padded cell. Overall, being inside the installation was like visiting a James Turrell light work on shrooms.

An objective description of Citadels is challenging since its subjective hallucinatory effects are inseparable from Munnik’s intent. Standing in the center of the space, various shapes blinked in and out of my visual field as my senses became increasingly skewed. The effect of Citadels, in many ways, was reminiscent of Brion Gysin and Ian Sommerville’s trippy 1961 invention Dreammachine, a rotating lightbox mimicking the physical experience of tripping. Only here, unlike Dreammachine, Munnik encourages viewers to keep their eyes open. It is also much more effective than Dreammachine, which, when I viewed the piece at the New Museum’s Brion Gysin retrospective in 2010, only made me sleepy. However, in Citadels, my distorted perception couldn’t be ignored.

It’s no mistake that Gysin and Sommerville’s experiment with Dreammachine, as well as the acid tests, occurred at a time of political turmoil in the early 1960s. Similarly, Citadels seems to derive from the same escapist impulse. Particularly in conjunction with Spriggs’s Gold, the installation became a psychedelic respite. After witnessing our potential capitalist downfall on the floor below, Citadels’s altered consciousness felt both much-needed and well-deserved, even if it was only for a moment before the nausea set in. That kind of self-flagellation isn’t pleasant, but these days it seems like a perfect reflection of how it feels to wake up and read the news every day. Given the extremes we’re living through, it’s no surprise many of us, including myself, see a lot of art through that lens.

Comments on this entry are closed.