Gardar Eide Einarsson, “Always Carry A Bible / All Cops Are Bastards,” 2007

Punk. Sus rastros en el arte contemporáneo

Museo Universitario del Chopo

Curated by David G. Torres

Until March 26th, 2017

Featuring: Tere Recarens, Martin Arnold, Johan Grimonprez, Federico Solmi, Dan Graham, T.R Uthco, Ant Farm, María Pratts, Iztiar Okariz, Chiara Fumai, Raisa Maudit, Fabienne Audéoud, Eduardo Balanza, TRES, Raymond Pettibon, Die Tödliche Doris, Mabel Palacín, Christian Marclay, Guerrilla Girls, Brice Dellsperger, Jordi Colomer, Pepo Salazar, Juan Pérez Agirregoikoa, Jota Izquierdo, Israel Martínez, Aida Ruilova, Antonio Ortega, Luis Felipe Ortega, Daniel Guzmán, Jimmie Durham, Mike Kelley, Tony Oursler, João Louro, Paul McCarthy, João Onofre, Santiago Sierra, Yoshua Okon, Miguel Calderón, Nan Goldin, Enrique Jezik, Guillermo Santamarina, VALIE EXPORT, Kendell Geers, Laureana Toledo, Sarah Minter, Semefo, DR. LAKRA, Gardar Eide Einarsson.

MEXICO CITY– I’m struggling to watch Aïda Ruilova’s 2009 video “Meet the Eye,” in which the actress Karen Black alternately attempts to seduce and crazily berate Raymond Pettibon between rapid edits. She’s wearing babydoll-style makeup, which gives her a subtly Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? vibe, and I’m hooked to the melodrama. But I have no idea what the argument is about, because I can barely hear the audio track over the sound of gunshots, a faint electroclash song playing somewhere, countless indistinguishable noises, and the invitation “Let’s go for it!” being repeated in a grating child’s voice.

The gallery is an ADHD nightmare. It contains not one, but two talking Mike Kelley works and several videos by other artists. In one, the Spanish performance artist Itziar Okariz is pissing on a parked car in the middle of New York City. On the other (source of the electroclash track) I catch a glimpse of what appears to be a dead-eyed princess dripping with cum.

By the time I turn back to Ruilova’s piece the loop has ended. My questions are unanswered. The curatorial strategy here leaves me with so many more.

From Raisa Maudit’s 2012 “FART: Global Art Fair”

Punk. Sus rastros en el arte contemporáneo, now on view at Museo Universitario Del Chopo, is sort of a mess. That’s not to say the work here isn’t good—it’s great—but the show is an overwhelming, over-stimulating experience that’s often draining when it should be wholly inspiring. I can’t think of another exhibition I’ve been to in which I’ve loved nearly every artwork yet couldn’t wait to get the hell out of each gallery. Maybe that abrasiveness is deliberate? The experience did, after all, remind me of trying to have one-on-one conversations with dear friends while a noise musician performs on the other side of a party in a squat. If the past 35 years have rendered audiences numb to “shocking” artworks, perhaps subverting museum-caliber curatorial conventions is the last punk gesture.

That’s a thought I might not have had, were it not for the fact that (I think) I entered the exhibition backwards. The galleries are stacked in a concrete box addition inside the museum—an airy 1902 glass pavilion that, appropriately, was home to Mexico’s famous punk market “El Chopo” until the late 80s. I started from the top floor, the library, where punk memorabilia is arranged in vitrines, more or less chronologically alongside didactic text. This part of the exhibition, at least for me, was surprisingly enjoyable. The text places punk in an art historical context, citing Dada, the Situationists, John Waters’ films, and Warhol’s factory as conceptual forefathers. Alongside the familiar narratives of the CBGBs scene and parallels in London, the curators discuss Spain’s Movida Madrileña—one of my favorite, under-historicized moments in subculture—the Spanish-speaking world’s more recent equivalent of the experimental Weimar Republic years. I got an undeniable thrill from seeing a video of all-female Basque punk band Las Vulpess’ cover of “Now I Wanna Be Your Dog” enshrined in a museum (in Spanish, the song translates to “I like being a slut”, and its broadcast on television sparked a debate about censorship, gender, and “decency” in Spain’s relatively new socialist democracy). From photos of drag icon Divine to punk band Eskorbuto, never had I felt more cool nerding out in a museum. Importantly, the show ties the influence of both European and anglophone punk to Mexican subculture in the 80s and 90s. That’s a topic I’m glad the show gave me an introduction to. (Indeed, I’d like to revisit Sarah Minter’s hour-long video “Alma Punk” from 1992 in a less overwhelming context. It’s a candid DIY document of Mexico’s punk scene from that era.)

Enrique Ježik, “La fiesta de las balas,” (The Bullet Party) 2011.

If the academic and “precious” vitrines of punk history and artifacts were unexpected, the gallery beneath it seemed like a contemporary assault on the culture of display—quite literally. The aforementioned gunshot sounds are from an Enrique Ježik sculpture, “La fiesta de las balas,” 2011. The piece comprises three bulletproof glass display cases, evocative of Damien Hirst works, riddled with craters from bullets. They’re installed in their own room, like a shooting range, but the sound from the shooting recording reverberates through half the museum. The piece stuck with me beyond my initial reaction (a teen boy destruction fantasy) as a commentary on both the cult of art object worship, and the futility of resisting it. Like Warhol’s “Shot Marilyns”, the piece’s value lies in it doubling as a record of the violence committed against it.

But “La Fiesta de las balas” also points to two of the exhibition’s most glaring problems: it’s one of the few works here that actually should be experienced as a physical object, and it’s loud as hell. There are only a few other sculptural works in the show, and at least half of them involve an audio or video component that’s competing with other sounds in an echoey gallery.

Still from Brice Dellsperger’s “Body Double 16“

And sound is a big, big problem for a show that’s overwhelmingly based on video. Don’t get me wrong: nearly every video here is fantastic. I spent untold hours diligently viewing relatively short works such as Raisa Maudit’s 2012 “FART: Global Art Fair” (in which the artist parodies the gallery/artist relationship in a tiara and semen during a fake interview with herself) or Ant Farm’s 1975 “The Eternal Frame,” in which the artists reenact the assassination of JFK, complete with drag Jackie O. But in such a busy exhibition, to expect visitors to sit through Dan Graham’s hour-long “Rock my Religion” is asking a bit much. If you’re curating a program with more time-based-media than a museum has hours, perhaps a gallery exhibition isn’t the way to go. I couldn’t shake the impression that Punk would’ve made a fantastic screening series and publication, with perhaps a much leaner gallery install where noise-emitting sculptures had more space to breathe. It felt like a missed opportunity for content with so much potential for event-based programming and critical writing—especially considering the museum has its own movie theater.

It’s frustrating to view video works when they’re all looping at different rates in a gallery context. There’s a rich history of subversive cinema as a collective viewing experience, and so many of these works would be better on the big screen. I am thinking especially of Brice Dellsperger’s “Body Double 16.” It’s short, but screams for cinematic treatment. In the piece, Jean-Luc Verna assumes a variety of characters in drag, committing various acts of violence against the other characters he’s also playing. The artist recreates scenes from A Clockwork Orange and Ken Russell’s Women In Love with surprisingly beautiful cinematography that makes the punk/masochistic content so much stranger.

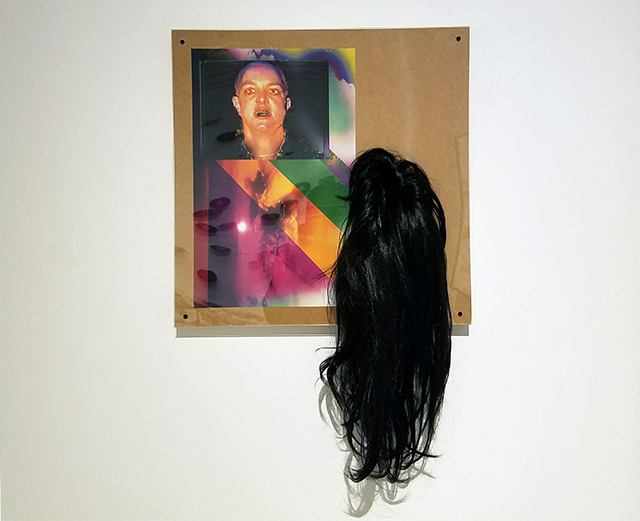

Pepo Salazar, “Yoga Alliance,” 2015.

It’s one of many highlights lining the ramp gallery (which is either the entrance or exit, depending on the route one takes). There’s really too much excellent work here to talk about it all—but I’d be remiss for neglecting Pepo Salazar’s assemblage “Yoga Alliance,” which is arguably one of my favorite artworks of the past few years. It comprises a digital print of bald Britney Spears, from her very public meltdown a decade ago, and a black wig hanging from the piece. It has a very “Punk’s not dead” (rather lurking in unexpected places) vibe, and the physical wig almost reads like an invitation to the viewer to join in the rebellion.

Install view with Die Tödliche Doris, “Das Leben des Sid Vicious,” 1981 (L); Christian Marclay, “Record Players,” 1983-84; and Guillermo Santamarina, “Frei vom jedem Schaden!” installation of albums thrown like a discus at the wall in the background.

Descending the ramp, through more video projections, the last piece I encountered (or the first for viewers who start from the bottom up) was Catalan artist Jordi Colomer’s “No Future.” The video follows an old car mounted with an electric sign bearing the titular text as it drives across European cities. The piece is from 2006, and as the “NO? FUTURE!” message crossed a likely expensive, Calatrava-looking bridge, it felt eerily prescient. Filmed just before the global recession and the political turmoil that ensued, Colomer seemed to know that punk would suddenly become relevant anew. If The Decline of Western Civilization is accelerating, at least somebody is still having a little fun while we’re along for the ride.

Jordi-Colomer-No-Future-2006

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 2 trackbacks }