Installation view of Valery Jung Estabrook’s Hometown Hero (Chink) at SPRING/BREAK (Courtesy SPRING/BREAK Art Show)

SPRING/BREAK Art Show

4 Times Square

New York, NY

On view until March 6, 2017

With its emphasis on supporting artists and curators rather than commercial galleries, SPRING/BREAK Art Show is typically the highlight of the exhausting Armory week frenzy. While the verdict is still out on many of the other fairs, I can confidently report that this one does not disappoint.

Oddly enough, the reason for this, seems to be at the nexus of the fair’s identity—artist-focused, themed curation. The official theme is Black Mirror, which as the curators describe it, is about seeing oneself through a lens. But for this show, that usually translates into ruminations on demographics and politics or rather, politics based on demographics. It’s reflective of a time in which most of us in the arts community are far more terrified by anything the president has to say or do than by the technological dystopia presented in the Netflix blockbuster Black Mirror.

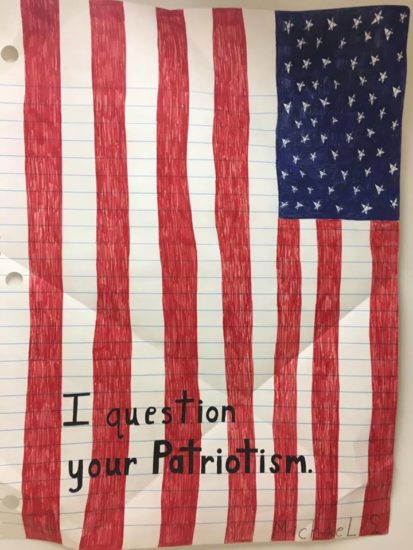

Work by Michael Scoggins in Katharine Mulherin’s American/Woman booth (photo by author)

Perhaps the fact that the whole thing takes place in a swanky hi-rise office building befitting of a news corporation makes sense in this context then. Set in the former offices of Conde Nast (a far cry from the worn-down Moyinahan Station), the fair, much like the government, resembles the victim of a hostile corporate take over.

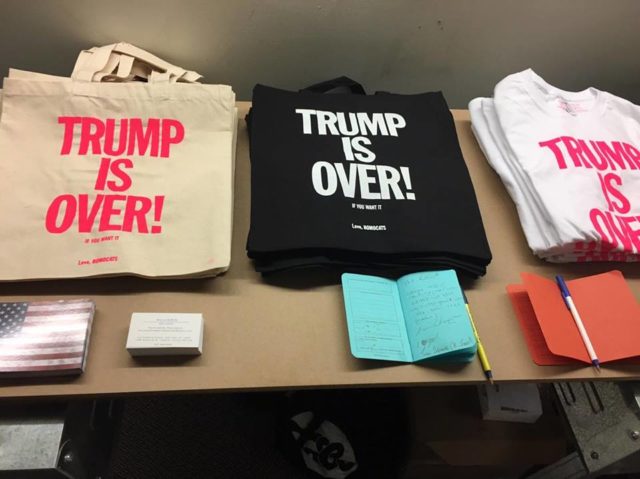

J. Morrison’s Trump Is Over totes (photo by author)

Despite the scattershot variation in subject matter, a significant number of works engaged with American identity. On some level, this is unsurprising since the country’s character seems to be under question due to the policies of the Trump administration. Refreshingly, the orange man himself didn’t make much of an appearance with the exception of tote bags by J. Morrison that say, “Trump Is Over.”

View inside part of Phil Buehler’s American Trilogy (photo by author)

While the totes were, in some respects, obvious, they did immediately catch my eye–the key to effective activist art messaging. Other art, not so much. Phil Buehler’s American Trilogy presents three round freestanding structures that immerse the viewer into an enormous panoramic photograph. The three photographs represent a stuffed animal-strewn memorial to Mike Brown in Ferguson, a solemn view of Saqib Muazaam Khan’s gravesite at Arlington National Cemetery, and a crowd shot at the Women’s March. Buehler’s installation seemed to ask: where are we and how did we get here? Instead of contemplation, though, viewers at the opening were using it as semi-private spaces for conversation. The installation and familiar images just weren’t inventive enough to achieve its desired emotional impact.

Debra Zechowski, “Ma, 1990 (Fran)” (photo by author)

Rooms that explored American identity from a more personal angle were more engaging. Take, for example, Debra Zechowski’s solo booth of paintings of blue collar Americans at home, curated by Joyce Chan. Culled from family photographs, these paintings fixate on the bizarre mixture of pop culture and homey accents that define rural American aesthetics. In one painting, a woman smiles holding up a Bart Simpson T-shirt while sitting in a worn, striped easy chair. Rather than poking fun at the, at times, garish and trashy tastes of Middle America, Zechowski’s paintings felt sensitive and sympathetic. They humanized a population that is, maybe unfairly, now associated with Trump supporters.

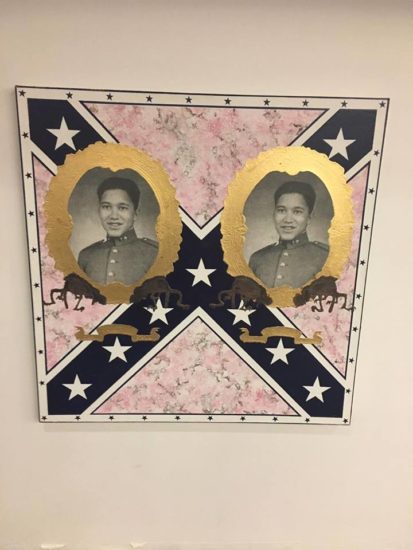

Startlingly, the Confederate flag also made a few appearances in the show as seen in the paintings of Michael Holman and in an installation by Valery Jung Estabrook. The Confederate flag is such a recognizable symbol of hatred that it is almost immediately alienating. But, both artists employed the flag as a means to complicate race and ethnic identity, the notion of the other and histories of subjugation.

Painting by Michael Holman (photo by author)

Displayed in one of the open central corridors of the 22nd floor, Holman (who is black) pairs the flag with portraits and documents from his family who fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. Flanking these works with monochromatic paintings emblazoned with “native” and “should have picked your own cotton,” these paintings reveal the troublesome and little-discussed history of black soldiers enlisted for the South.

Like Holman, Valery Jung Estabrook’s installation Hometown Hero (Chink), which was curated by Debbi Kenote and Til Will of Open House, focuses on the American South. But rather than a history lesson, she combines contemporary romanticized notions of the Confederacy with issues of assimilation. Stepping in this installation felt like walking into a living room in the Deep South. A portrait of Robert E. Lee hangs on the wall, a display of shotguns is on another and a recliner draped with the Confederate flag sits next to a table covered in beer cans. What raises this décor beyond a redneck period room is that Jung Estabrook renders this entire scene in fabric. This adds an intimate, handmade quality to the interior.

Installation view of Valery Jung Estabrook’s Hometown Hero (Chink) (photo by author)

Opposite the Confederate recliner, Jung Estabrook places a television that features a K-pop avatar singing a folksy country song. With this unexpected juxtaposition of Asian aesthetics within an otherwise symbolically white space, the artist, who grew up in southern Virginia, reveals the internal conflict between the yearning to belong and the traumatic loss of culture of origin during assimilation.

Hometown Hero (Chink) presents a rarely depicted view into the tensions inherent in being Asian American within the American South and I found that electrifying. Art is most compelling when it gives voice to new stories. Making this all the more special, art fairs, which tend to be more akin to a really expensive street fair than a museum experience, don’t often have room for works like Estabrook. Thus, the work’s very existence makes SPRING/BREAK a welcome outlier in the expanse of Armory week.

Comments on this entry are closed.