Alice Sheppard and Laurel Lawson of Kinetic Light in “Broken Intent” (Photo: Scott Shaw)

AXIS Dance Company, Marc Brew, Kinetic Light, and Marissa Perel: Our Configurations

The Theater at Gibney Dance

280 Broadway

New York, NY

March 4, 2017

Two audience members lick the pant leg and cane of performer Marissa Perel. While this happens she recalls awkward and downright insulting moments related to her disability. In one particularly horrifying story she tells the audience about a subway rider who called her a “bitch” after she refused to answer why she had a cane.

This, at once, funny and cringe-inducing moment was a part of Perel’s performance (do not) despair solo, one of the four performances featured in Our Configurations at Gibney Dance. In a short post-show discussion with the performers and NYU professor Hentyle Yapp, Perel defined her work as “an act of resistance against normativity.” This could be said of all of the performers in the show, including Marc Brew, AXIS Dance Company and Kinetic Light. Despite attempts at increased inclusivity at most arts organizations, abled-bodied performers are still largely the norm. And that’s a shame.

Luckily, Our Configurations provided a compelling challenge to the assumed limitations of disability–an important rebuke of the lack of representation of disabled performers. The evening, like Perel’s awkward but powerful moment with her two “consensually submissive volunteers,” showed how performance can be a tool to express the experience of disability, as well as the, at times, fraught interaction between disabled and able-bodied people.

Marissa Perel with consensual submission of audience members in “(do not) despair solo” (Photo: Scott Shaw)

The sold-out evening of performance showcased a diverse range of expressions and choreography. Some of the work was more conventional with movements familiar to modern dance like AXIS Dance Company’s Dix Minutes Plus Tard. Others were closer to performance art with a multidisciplinary combination of performance with reading, video or sculpture. Admittedly, which could be my own bias as an art rather than dance critic, I found the latter more compelling.

Take, for example, Perel’s combination of choreography and reading. She prompted the audience to recite a selection from her dance criticism essay “I Want/I Vomit” (“I love your body even when I don’t understand it. I love your body even if I am afraid of it…”) and read selections from artists and writers like Gregg Bordowitz, Emily Roysdon, and Maggie Nelson. Perel, who lives with chronic pain, required the assistance of an audience member to hold the microphone and find the right page in her chosen reading. By the varied voices in the readings, as well as the volunteer’s slight nervousness, Perel seemed to be trying to find a language for both pain and the emotional toll of care-taking.

Marissa Perel with consensual submission of audience members in “(do not) despair solo” (Photo: Scott Shaw)

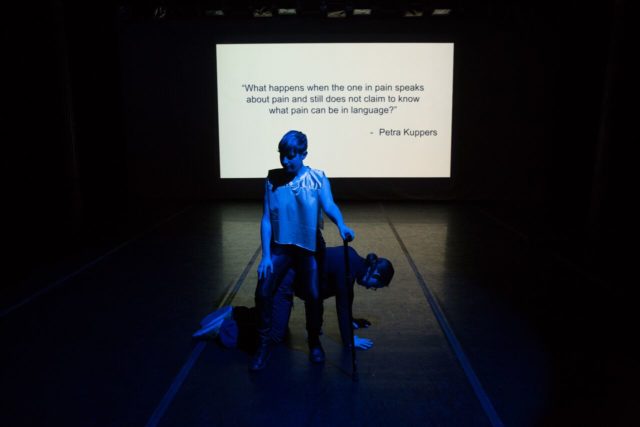

These sentiments made the conclusion to her performance more significant which involved a wordless physical performance. With the lights dimmed and Fleetwood Mac’s Long Distance Winner playing, a slide projected a question by Petra Kuppers, asking, “What happens when the one in pain speaks about pain and still does not claim to know what pain can be in language?” In front of this, Perel sat on another audience member’s back, frequently adjusting, lifting her head and petting the volunteer’s body. In stillness and her interaction with the volunteer, Perel communicated both the limits of choreography for a body in pain and the supportive intimacy between disabled and able-bodied people.

While Perel transformed audience members into able-bodied assistants (and sometimes, props), others, like Marc Brew, engaged with the ableist gaze. Brew, who is paralyzed from the waist down, appeared on a darkened stage in his wheelchair, while a video projected behind him. The video showed Brew dancing, which, for him, means extending his arms, bending down over the wheelchair and twisting his body, in a subway station. His image is reflected in the glass of an escalator–an apparatus that he cannot use. The camera occasionally caught the curious and sometimes, judgmental glances from passersby at Brew, a gaze that disabled people frequently endure in public space.

Marc Brew in “Remember When” (Photo: Scott Shaw)

After the video, Brew performed a repetitive dance, illustrating tension and release. Much of the performance focused on his arms as he clasped and unclasped his hands, circled them above his head, grabbed his legs and extended his arms fully. He also folded and contorted his body into angular poses. In a couple moments, Brew exposed his stomach and lifted one of his legs, thin from his disability, up near his chest. Overall, the performance and his use of exposure felt both visceral and graceful.

The most innovative work in the show, though, was Kinetic Light’s duet performances To Bend A Bough and Broken Intent, Granted, the first dance To Bend A Bough was deceptively slow. Mostly centered on the floor, the two performers–Laurel Lawson and Alice Sheppard–crawled towards each other, pushed each other away, bent and reached upwards, stretched and, at times, held each other aloft. It seemed to reflect alternating desire and rejection.

Alice Sheppard and Laurel Lawson of Kinetic Light in “Broken Intent” (Photo: Scott Shaw)

However, Lawson and Sheppard’s subtle interactions disappeared in the second performance, as stagehands dragged two ramps onstage and Lawson and Sheppard strapped themselves in wheelchairs. While adapted from a larger-scale performance staged with a full-scale architectural ramp, it still made for a jaw-dropping visual experience. More active and strenuous than the initial dance, Lawson and Sheppard rolled down the ramps, spinning around each other like ice skaters. At one point, Shephard flipped Lawson over her while still in the wheelchair in a somersault. The utter physicality of the performance was staggering, as was the duo’s powerful reclamation of the utilitarian wheelchair ramp as a performance prop.

At the end of Kinetic Light’s performance as Sheppard bent back, holding Lawson on top of her with her wheels in the air, someone behind me yelled out, “Yas!” I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Comments on this entry are closed.