Deborah Castillo wears a lot of hats as an artist. And wigs. Originally from Venezuela, Castillo often blurs the lines between performance, video, photography, publications and even jewelry making. What binds these endeavors together is a sharp, critical wit (usually trained on political institutions) and flair for the dramatic. That might manifest as necklaces in the shape of misogynist slurs in Spanish or over-the-top fictional narratives involving art world kidnappings and embezzlement.

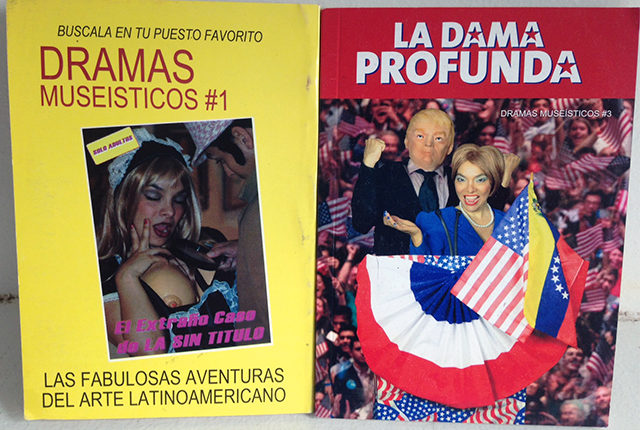

I met Castillo (who now lives in Bushwick) at her book launch at Mexico City’s Aeromoto, an artist-run library of contemporary art and artist books. She was celebrating the release of “La Dama Profunda / Profoundly Yours”, the third installment of her “Dramas Museísticos” series. I was immediately drawn to the format of the publications—they’re fotonovelas, comic-book like novels that use photography instead of illustrations. They were a popular form of mass media in Latin America, but are less known in the US. They’re fun and extremely approachable—even though Spanish is my second language, they’re easy reading, and the third book contains an English version of the story.

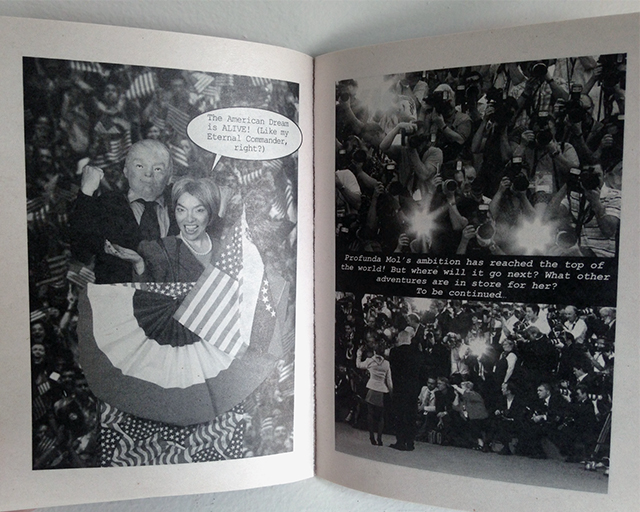

The books follow the soap-opera-like story of Castillo’s alter ego Profunda Mol, an ambitious woman who social climbs through the art world of her native Venezuela. Profunda navigates (often through seduction) a world of corrupt officials, along the way becoming the Venezuelan Minister of Culture, an Ambassador to the United States, and ultimately Donald Trump’s fourth wife.

We talked about fotonovelas, sexuality in the art world, and the crappy political climate.

“El Secuestro de la Ministro de Cultura”, Dramas Museisticos II 2013. from Deborah Castillo on Vimeo.

How would you summarize “Dramas Museísticos”?

La Dama Profunda is a project I have been working on for eleven years and counting. The saga comprises 3 different books (“El extraño caso de la sin titulo,” 2006 ; “El secuestro de la Ministra de Cultura,” 2013, and “La Dama Profunda / Profoundly yours,” 2016).

The book is a parody and critique of the roles of women throughout history who have used their sexuality to raise their social stature and manipulate figures of power.. In the first two books you can see how Profunda Mol’s uncompromising ambition took her from a life as a gallery cleaning lady to becoming the Minister of Culture.

In the third book, she was named ambassador and shocked everyone with her life of luxury, excess, and debauchery in New York City. It was here that the golden imperial doors opened in all of their splendor, giving her access to the greatest world power; something unimaginable to the maid-turned-minister.

You’ve mentioned that a lot of North Americans have never heard of fotonovelas. It’s seems like such a logical medium for artists right now—especially considering the boom in small publications and the frustrations that come along with video. Personally, I really enjoy the fotonovelas because Spanish is my second language but they’re so easy to follow! How did you end up using the medium?

The fotonovela is something that is in my Latin “genes.” Remember that from Spain came the “novela folletín” (serialized novels) of the 19th century. This was a more commercial than literary writing, elaborated in small leaflets or in the lower parts of the newspapers. Many of the engravings had sensationalist scenes with improvised plots and this influenced the industries of the soap opera and telenovela (Venezuela, my country, was a leader in this field for decades). Some of these audiovisual productions were condensed, through still motion photos, in small periodical magazines called “fotonovelas”. These publications were very popular in the ’60s and’ 70s and even the early ’80s.

I remember them in my childhood, when I saw them for sale in the kiosks, curiously situated between pornographic magazines, lottery tickets and sweets. Later the production of these magazines disappeared and they remained like vintage objects with a cult following. At the beginning of the 2000s I found a street club of readers who exchanged these magazines as if it were the store Blockbusters, and this activated all my childhood memories. I immediately recognized in this medium a perfect platform to spread my work.

Could you talk about how Profunda uses her sexuality? I think it’s brave to tackle issues of gender and class through this almost “drag” persona.

Profunda “The Sexual Dame” has been an excuse to explore a parody of a stereotype that’s common in Venezuela [the power-hungry woman], and many other countries of the world. My work has always been a response to these systems of sexual power. Profunda is a platform that provides an analysis of issues of gender, desire, power and corruption—issues that are impacting our society more than ever before.

And yes! You are right: I have taken a path that has not been easy. I do not soften my work and I think sometimes this is annoying to the public.

Do you think dealing with sexual stereotypes is especially a challenge for women in the art world?

Women face a lot of challenges —not only in the art world, but in any industry. However, to be honest, I do not like categorizing artists as “women artists”/”male artists”. I know this is something that exists, but I just do not want to accept it as it perpetuates lots of cliches.

You also make jewelry (I really love your necklaces with different Spanish words for “bitch”). Could you talk about that project?

I have worked with the theme of stereotypes with different media. “Free Speech” is a body of work that addresses the stereotypes attached to immigrants and those without power. I analyze the way women have been socially labeled. I propose a way of writing from a performative approach using the body.

Speaking of which, you said it’s so hard to be funny in your second language. That’s a problem I can certainly relate to! But I have to say, your English language fotonovela is hilarious. I love the scene where Profunda is on the phone arguing about a Frank Gehry-designed museum she’s embezzled the funds for. Where do you think your dark sense of humor comes from?

I think my dark sense of humour comes from a sense of frustration—having to face some idiosyncratic characteristics of your own culture that you do not accept. Corruption, bad education, social climbing via robbery, some behaviors and relationships in the art world…..all this creates a nasty landscape that is unacceptable for me. I choose a dark laugh instead of a bitter cry.

(Are we allowed to talk about this?) I’d like to mention that I have a stack of your books because you didn’t feel comfortable bringing them back to the US through customs, given all the recent problems people have had with materials considered subversive to the Trump regime. What’s it like being an artist who left a country with a repressive regime, only to find this new political climate shortly after your arrival? Do you think people will start self-censoring?

The scenarios and social contexts in Venezuela and the United States are very different and perhaps not comparable. However, I can not help but feel great concern. I lived in Venezuela when all this began 17 years ago, and have seen it degenerating into an increasingly violent and conflictive scenario. In fact, the wild repression of freedom of expression was one of the main reasons I came to this country.

I was a victim of this repression in 2013 when I was publicly denounced on the government television station for having exhibited a work that criticized the abuses of power by military dictatorships and their iconography. The journalist who talked about my work suggested I receive some violent form of punishment. This generated a threatening public response by government supporters which made me recognize the imminent physical danger for me and my family.

I closed all my social media accounts, I stayed at home for a couple of weeks and I stopped any spread of my opinion or images. In a few weeks I had moved to NYC and I left my country with a deep sense of fear despite the fact that nothing physically had happened to me. Being intimidated in public by someone who represents a criminal power is a very effective silencing tool. Self-censorship is one of the most subtle forms of violence that a government can exert over the population. It is a way of controlling the words, actions and even the thoughts of people without being noticed: something quite Orwellian. However, I have faith that the institutions in the United States are strong enough to withstand and combat any excess of authoritarianism that may arise in the future.

I worry a lot about the United States becoming increasingly culturally isolated given how international travel seems to become more and more difficult. Do you see a power shift where Latin America’s art scene is emerging more from the dominance of New York?

Like every chapter in history, nothing is completely good or bad. I believe that a market in Latin America is consolidated where high quality work is being done. It is beginning to see inwards more than outwards and that is positive for us. I think power centers are moving, and maybe I want to believe that Trump is giving us this opportunity!

From my brief experiences and outside perspective, it seems the art world in Latin America is much more tied to politics. So much artwork tends to be political, and yet it seems there’s much more of a relationship between governments and arts funding than in the United States. Do you find this to be true? What’s the political game like that artists play?

I believe that this strong tendency towards political art is due to the terrible social reality that we have faced in Latin America historically. Those experiences have informed the lines of production of contemporary art. For my part I am interested in exploring sexual stereotypes; questioning the values of social organization; questioning social climbing within the art world; and the relationship between desire, power and the political mythology of today’s society.

On that note, is there any wisdom you can share with Americans based on your experiences dealing with Venezuela’s own fucked-up leadership?

Yeah. I would say, “Just be aware”. Especially the young people.

Comments on this entry are closed.