Angela Bulloch, Heavy Metal Body

Angela Bulloch

Heavy Metal Body

Esther Schipper, Berlin

Until June 17, 2017

The following might sound like a backhanded compliment, but stick with me. Angela Bulloch’s gorgeous new sculptures, on view at Esther Schipper, are happily in sync with what we traditionally think of as summer fare: big, colorful, distracting and kid-friendly. All that’s missing is the popcorn.

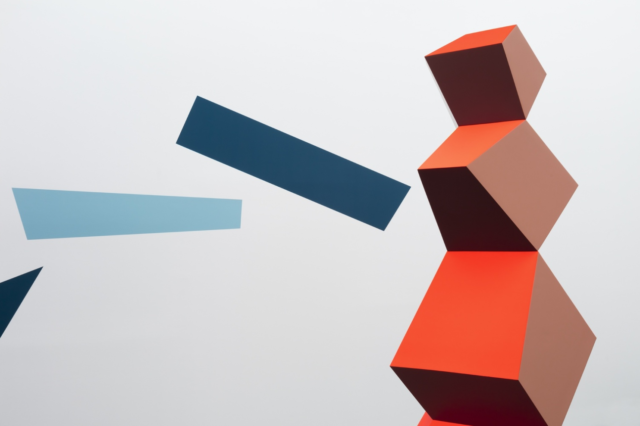

Taking up a narrow half-hall in the Schipper gallery’s new (and very posh) Potsdamer Strasse cavern, Bulloch’s three rhomboid steel pillars in three sizes (S, M, L) vibrate with barely contained energies. Plunked beside glaring white walls, these hotly colored works appear to twinkle, jerk and throb, much in the same way masses of LED lights can appear to spasm and fidget. This odd conflation of masses—of metal and a distinct sense of instability—sparkles, causing the viewer to distrust their own eyes in their attempt to make the sensual experiences of awe and enchantment coalesce.

This is a small exhibition, only three sculptures—granted, large sculptures—plus a complementary mural. Compared to the many sprawling museum shows on offer in Berlin during the summer, one could even call Bulloch’s exhibition more of a tidbit than a tale. However, and this is crucial to why I reckon the work needs attention, Bulloch’s sculpture’s act out an incongruity that has parallels with our off-kilter times, and are therefore worth more than their immediate half-a-show appearance initially suggests.

Bulloch’s work here thrives on odd and arguably at-odds pairings: the soft, party-time playroom colours and the hard, pointy steel; the rhomboid shapes that speak of calculation and deeper geometries that are plunked on top of each other in an inconsistent, even wonky fashion; the towering heights and hefty girth combined with startling colour patterns that make each sculpture appear to float like bouquets of birthday balloons. From these incongruous combinations of bulk and flash, of big metal objects made to look like toys, I see a parallels with a myriad of contemporary dysmorphisms.

How often does one feel that one’s physical self, one’s actual mass, is not in tune with one’s over-stimulated perception? We have bodies and are contained within our bodies, yet today we often feel disconnected from our core physical reality because our sense of self is fragmented across many platforms. Thus, we are both the mass of metal and the decorative, pretty shellac. As our lives online grow more detailed and fabulous, the dissociation grows and grows, but our physical bodies remain the same, remain solid and tethered to one plane. This is why Bulloch’s work speaks to me: it embodies, sorry for the pun, catches and makes still, an incongruity that we experience mostly if flashes and sudden fugues.

Angela Bulloch, Heavy Metal Body

All my projecting aside, I note that the didactics attached to the exhibition make a lot of serious noise about Bulloch’s geometry play—her mathematical point and counterpoint, of the fact that the pillars are constructed as stacks of misaligned, intentionally pattern-breaking polygonal shapes. We are meant to read these works as geometric “interventions”, as rule breakers. Sure, of course, but what strikes this viewer first, and what lasts, is how damned pretty these towering hulks are, how perfectly cute. When you paint your metal whatsits with powder baby blues, skin tones, and hot candy colors, expect adoring sighs.

Since I first started looking at Bulloch’s art in the early 2000s, I’ve noticed that critics are reluctant to describe, or are just unable to see, the visceral qualities evident in so many of her works; the sexy and/or spooky charm, the way the works actually make you feel. Too often critics prefer to figure out how her grids mark and chart space or how her mathematical fussing denotes various formal instabilities. But Bulloch’s keen sense of colour and close attention to the play of light on treated surfaces, to how brightness and emptiness can enfold each other, as well as the monumental, bigger-than-human scale of the majority of her works, conveys also a deep connection to math’s opposite, the sensory.

Bulloch’s work makes the viewer aware of their own presence alongside the objects (as well as our innate, arguably babyish attraction to spectacle), usually by inflating—over-sizing—the raw, primal, and joyous experience of eyes processing colour and shape. The sculptures at Schipper are a perfect example. You don’t just stand beside the pointy towers, you do a slow mental waltz with them. I wanted to hug the short, chubby one, as it reminded me of a snowman. But I’ve been to a gallery before.

Unfortunately, these beautiful and compelling works are not best displayed in their current presentation at Schipper. Crammed into a narrow (in comparison to the rest of the joint) half hallway, the sculptures crowd up against each other. Furthermore, the tallest of the trio reaches past an exposed beam, breaking the line of sight. Bulloch appears to have addressed this inadequate space by crafting a mural that bumbles along the walls that encase the sculptures, but no amount of decoration can distract from the simple fact that such lively and energizing works need room to dance.

Comments on this entry are closed.