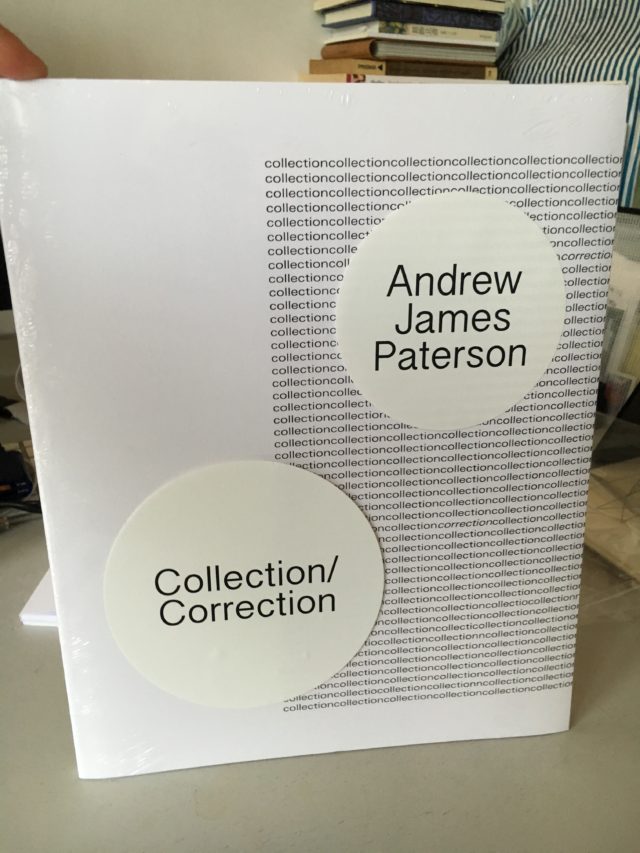

Andrew James Paterson

Andrew James Paterson

Collection/Correction

Co-published by Kunstverein Toronto & Mousse Publishing

Every city should have an Andrew James Paterson. Pity we cannot clone him.

Since the late 70s, Toronto-based Paterson has produced a mountain’s worth of material in a mountain range long list of disciplines: from seminal New Wave music to Super 8 films, neo-noir novels to ground-breaking critical texts blending art writing and fiction (aka ficto-criticism), diaristic video pieces and digitally sourced art to performed lectures to concrete poems to performance poetry to theatre works. And that’s the short list.

He is arguably one of the most influential figures in Canadian art alive today, and I do not make such statements readily nor lightly. A Toronto without him is unimaginable.

And now, there is even more proof. Collection/Correction, an anthology of Paterson’s critical writings, concrete poems, and film scripts provides a kind of Paterson 101 to new readers and confirms what the rest of us already know – Paterson is an agile and beautifully free thinker, and has always been way ahead of his time. What the hell took this book so long to arrive?

I reached Paterson by email and asked him to “have fun with my questions”. You get what you ask for.

RM Vaughan: How did this book come about?

Andrew James Patterson: Collection/Correction developed out of a collaborative friendship with the editor slash curator Jacob Korczynski. We’ve known each other since 2005 and Jacob has curated my work in a few programs. One night he posited the idea of a book surveying my writings. If only to leave traces of my existence, I counted myself in. We agreed there would be three main components: my concrete writing or language drawings or whatever we might want to call them; four specific video scripts; and four ficto-critical pieces I had written for IMPULSE magazine much earlier in my life or career or whatever the trajectory. It was paramount that this book would mix newer and older work, that all the work could exist in the present tense as well as historical contexts. Also, we agreed that a few key colour images were crucial to the book’s intention. So thus the still images from [the video works] “Passing” and “Eating Regular”.

What was it like looking back at your own writing?

I’d say it was different with the fiction and ficto-criticism [a practice that merges elements of fiction, theory and criticism into stories]. The concrete poetry was too recent for me to feel distance from. It was like, yes go with the ones that work the best on paper but which could also be performed as it was important for performativity to be visible. The IMPULSE writings were earlier, when in many ways I was a different person. I feel more distant from those pieces. [And] I did find myself looking back to when I began experimenting with concrete poetry. I can trace it to a performance piece I did in 1998 called Symptoms of Whatever. But I must have at least flirted prior to that. Some of these word drawings and sculptures come out of my interest in art song lyrics that play with nonsense and repetition. I also thought about when I became fascinated by typos. Some time in the 80s, when I meant to write Freud but wound up with Fraud! Do the same with Jung you get Junk, and so on. I had incorporated this little fetish into the video “Who Killed Professor Wordsworth” (1990) and a text plus photo piece I contributed to the artists’ book I’ve Got to Stop Talking to Myself (edited by John Marriott, 2000). So, although the concrete poems in Collection/Correction were mostly made over the previous few years, there was indeed a connective to earlier works.

Did you change any of the text(s) in preparation for print? If so, how did that work and/or what did it feel like?

No, all the texts are verbatim. I could seriously re-write any of those pieces but then they would be different pieces that should have different titles among other changes.

You are a pioneer in the field of ficto-criticism. How has the genre changed since you first experimented with it?

You flatter me. The first person I associate the term ‘ficto-criticism’ with is Jeanne Randolph, who I consider a pioneer and whom I admire greatly for her mixture of an almost conversational prose and her very acute observations. I’ve always liked the mixture of fiction, even with plots to keep things grounded, mixed with observations and critique. I mean, my favorite section of Chris Krauss’ I Love Dick is that section where she forgets about Dick Hebdidge and Sylvere Lotringer and presents her own fascination and admiration mixed with critical observation of the performance artist Hannah Wilkie.

I think there are many art writers who work fictional elements into their reviews. Often I wish they’d simply write fiction.

Art writing in general has changed enormously since you first became an art writer. In a world obsessed with click bait and link hits, is there still room for experimental prose about art?

Well, there certainly should be. There certainly should be space for writers/critics/observers to use ‘experimental’ (I guess meaning obtuse or not didactic or simply not literal) strategies to play with art that is in circulation or on display. But where to publish or read such writing? Well, there are personal blogs, but what about the media? I mean, what is the media? Where do you think there is room or space for art writing that is not promotional and is not simply describing the work to a potentially appreciative but passively accepting audience? What indeed is ‘the media”? Print? Well, I’m a geezer, so I still actually read a newspaper each day, as well as online posts. What percentage of works exhibited receive any coverage? Why do some galleries or artists get covered and not others. Why is there so little art writing in the mainstream media? The cliché is that art is considered an elite or minority interest. In Toronto, I miss something like LOLA, in which the writing and critical commitment was wildly uneven to say the least; but it did provide a forum for both serious contestation and also for casual observations that could effectively trigger other maybe not so casual observations and that is known as a dialogue.

I think there is a balance between somebody writing about themselves in the process of writing about exhibitions or presentations and somebody just writing about themselves, at the expense of the exhibitions and the artists in those exhibitions. The latter tends to get my back up. I want good creative prose in art writing, but I don’t want fiction that bypasses criticism. If you want to write fiction in its own right, then of course go and do so.

I haven’t actually been reading that much ‘art writing’ recently as I feel somewhat distant from ‘the art world’. I mean, I don’t exhibit that frequently. I’m best known as a video artist (that may be changing with this book) but I’m not exactly omnipresent on the festival circuit and my videos, well, are they really videos? They consist of graphic images or images constructed within the editing systems themselves. They could be labelled ‘materialist’. I feel I live in a very small corner and I don’t feel that’s particularly such a bad situation.

Do you regret and/or disagree with any of the positions you took 30 years ago?

Well, who doesn’t? If someone hasn’t altered their work within that time-frame, they’ve either blissed out, are so rich that they can afford to cease thinking, or they are an idiot savant. With Collection/ Correction there are works not in the book that I think are better than some of the works in the book. But if one is committed to making a book that coheres as a book, and in the process trusts an editor who has more than earned that trust, then those decisions are made and thus those omissions happen.

I do look at the IMPLUSE writings and realize that I was a very different person then. I was repressed and fascinated by particular repressions. I was suspicious of all that proclaimed itself to be liberated and free or open. I thought that superficially free space was actually highly regulated. I thought there were grids where there didn’t appear to be grids. I liked paranoia. I thought it made for good art. I went though my punk phase in the late seventies. I liked restricted options.

Your writing has always advocated a relentless questioning, and, in my reading, a discomfort with perceived/received truths. Is there still space in our pointing-and-shouting culture for the ambiguous, the uncertain?

Has it? I mean, all of my writing? I’ve written puff pieces and maybe even calling cards. But yes, I hope that a difference between the bulk of my writing and conventional narratives or promotional art writing is that closure is refused, that contradictory perspectives are not only permitted but encouraged. In fact, they are mandatory. I think there has to be space for the ambiguous, the uncertain and more, I think there has to be space where one can entertain a first person perspective and not have it assumed to be autobiographical. With shorter and shorter attention spans, of course that becomes compromised, to say the least. I can be supportive of anybody who will entertain a seemingly absurd premise and then follow through on it, who can make their case or ‘prove it’. I like meta-writing. But I will support blatant propaganda. Either I agree or disagree of course, and I don’t spend much time with it because “I get it”. Like identity politics: I generally prefer them to be outside of art and not even calling themselves art, but I will support their right to exist and I dislike it when somebody identifies themselves racially, ethnically, sexually as part of their work or their argument and then gets accused of relying on ‘identity politics’. Who decided that form and content were oppositional? Clement Greenberg? Who decided that radical content should rely on conservative form to be populist and accessible? Silly social-realists. I think radical content demands radical form, but that of course is merely my opinion.

In 2015, Canadian Art magazine declared the art review obsolete. Thoughts?

Well, I so infrequently pay attention to Canadian Art, I’m afraid. Is this of a piece with David Balzer’s Curationism? Is this statement in tandem with a post-critical world that bears an astonishing resemblance to a pre- or non-critical world? In which the only criterion is whether or not the artist has talent? In which reviews are expected to be promotional puff pieces?

There are reviews and then there are reviews. There are those for people art-walking who would like to read recommendations and to be warned about exhibitions which are time-wasters. Of course, I have gone to many exhibitions or movies simply because critics whom I can’t stand have panned them. Sometimes this has paid off and sometimes the fools have actually been correct.

And then there are reviews or overviews that are intended to be dialogical… to the artists, to the galleries, and to what for better or worse is the ‘art community’. If that discourse ever gets lost….perish the thought and the consequences. Of course there are people who don’t have time to read anything with too many four syllable words. But individuals of many stripes who appreciate intellectual discourse are not in any hurry to become obsolete. Thus I consider this Canadian Art quote to be either posturing or old-fashioned stupid.

When you meet young art writers, what do you say to them about writing? Where on earth to begin?

Do we mean writing about art or writing that is art? For art critics or observers, hmmm. Make sure you have at least one other source of income. Find a voice that mixes subjectivity with an ability to outline visual details. Get to know the friendlier editors and also artists. Try to get some old fashioned print publishing happening as well as your own blog or online publications. Mix with different audiences.

I’ve always loathed the separation in Toronto and in other centers of the visual arts and literary ‘communities’. If your writing is performative, perform, unless you have stage fright. Maintain a profile in the visual arts world. Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. Go to book launches. Don’t wait until your ninth life! Learn to work with editors and collaborators. Be a solitary mad artist up until the point when you need to be working with others, and then banish the solitary mad artist cliché. Treat writing like an addiction or a bodily function.

Comments on this entry are closed.