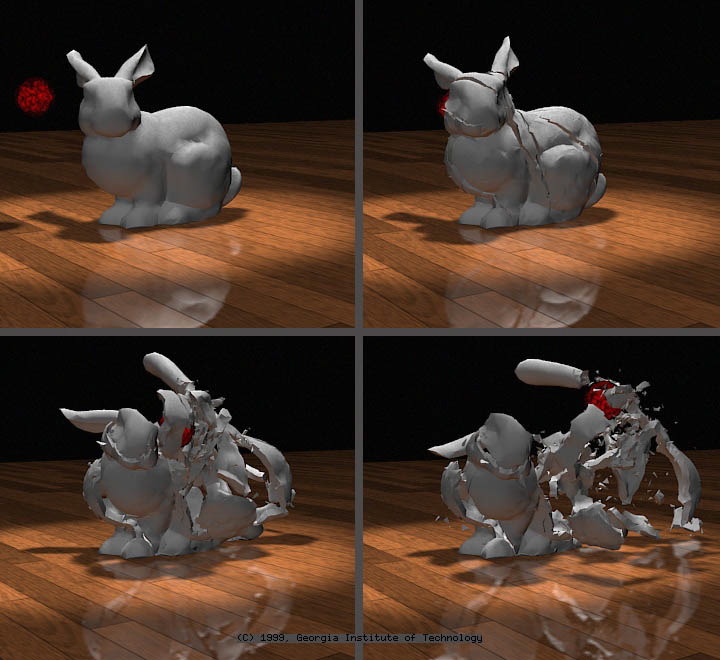

The Stanford Bunny. Three-dimensionally scanned from this terra cotta garden decoration in 1994, the Bunny model has since become one of the most commonly used tests for a wide variety of 3D research projects

[Editors note: IMG MGMT is an artist essay series highlighting the diversity of curatorial processes within the art making practice. Kevin Zucker, today’s invited artist is represented by Greenberg Van Doren in New York. He has had numerous solo exhibitions internationally, most recently Standards and Anomalies at Arario Beijing, where he showed work that incorporated imagery discussed in this post. His next project will be a two-person show with Hilary Berseth at Eleven Rivington (NY) in October.]

“These are the archetypes of a new world. They don’t need you or me. They’re representation for machines.”1

I’ve been collecting documentation of objects and images used in the development and testing of digital imaging and3D modelingtechnologies for a few years, and have thousands of them stashed on a hard drive and a list of links to databases with literally hundreds of thousands more. The twenty presented here are representative highlights that I think epitomize the inscrutability, banality, anachronism, and the straightforwardly artless presentation that characterize most of the collection. Those qualities, contrasted with the weird aura possessed by these analog “originals” of digital representation, make for the unsteady balance of gravity and absurdity that first got me interested in collecting them.

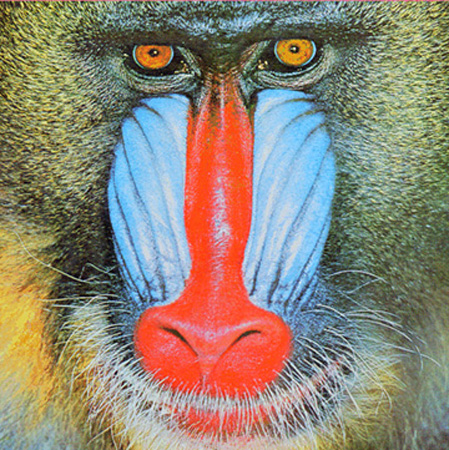

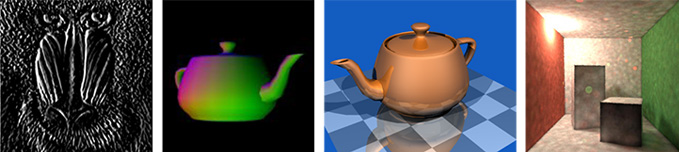

While the “end user” rarely sees any of these images or objects, a handful of them (Lena, the mandrill, the Utah Teapot (all below), the Stanford Bunny (above)2 and the Cornell Box (below)3 ) are well known to the point of being iconic within the digital imaging research community. They have even become the subjects of inside jokes between programmers and animators: 3D models of the Utah Teapot are hidden in Pixar’s Toy Story, a screensaver that comes as part of Microsoft Windows, and the Simpsons episode where Homer stumbles into a computer-generated “Third Dimension”4

The Utah Teapot. Modeled in 1975 from this original, the Teapot has become another standard test object used in a very wide variety of 3D applications

Lena. Scanned in 1973, The Lena image has since become the most widely used standard test for a variety of image processing applications

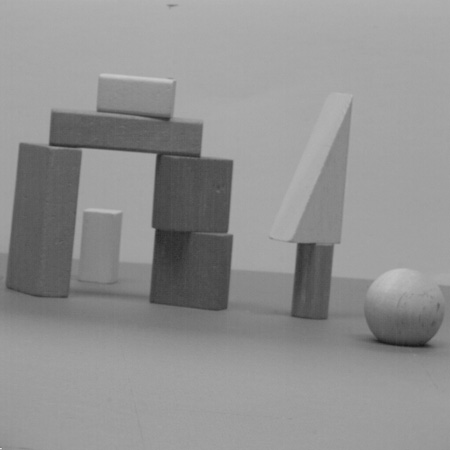

The Cornell Box. A physical model photographed under controlled lighting conditions, the box is intended to be used as a standard for comparison when judging the accuracy of lighting in 3D renderings

The Mandrill. Another very widely used test used for image analysis and computer vision research

Lena, probably the best known of all of these images because of its ubiquity as a standard quality test, is the face of Playboy “Playmate of the Month” Lena Sjooblom, originally cropped from the centerfold in 1973 by engineers at USC5. It is still in wide use today in spite of technological advances, past controversies over copyright, and ongoing questions about the politics of its source and content6.

The centerfold source of the Lena image.

Lena in use in compression tests

The rest of the images and objects shown here are more obscure, taken from data sets that are freely distributed for research purposes. Some of their applications include: image quality tests; benchmarks for the measurement of processing performance; hardware, software and printer self-tests; the development of synthetic lighting techniques for rendering 3D graphics and animation; statistical shape analysis; the modeling of traffic patterns, and samples for training facial recognition software and robotic/machine vision.

[From the top left] The Mandrill image, Utah Teapot and Cornell Box models in use, and The Stanford Bunny model

The Bunny as used in an animation

These fields of research have developed rapidly and become important influences on our culture. Virtually everything produced for the mass market is now designed in 3D software that made use of a Bunny or Teapot test model at some point in its conception. From the compression of the jpegs we see online to the CAD software used to design the monitors we view them on, the results of research using these test images and objects have been seamlessly integrated into many aspects of daily life.

An image from a standard stereoscopic vision test set

If you have any inclination toward science fiction, it’s appealing to view the realm of 3D modeling and digital representation as a discrete and clearly defined universe, a parallel reality to our own. In that universe, the objects and images shown here would constitute some of the Platonic forms upon which everything else was based. Even if that sounds overstated, it’s safe to say that the archetypal images and objects that come from our analog world (except for the “as used” images above, the photographs shown here are straightforward documentation of things from the physical world) structure a digital domain that in turn exerts an influence on the way we see and make things.

Another image from a standard stereoscopic vision test set

From the IMM face database. Images from this database are used for testing and development of software for applications like facial recognition and character modeling

While the researchers’ original choice of some of these images as standards may seem arbitrary or eccentric, it’s important to remember that they were never intended to function as representation in the normal sense of the word; they aren’t meant to communicate something about the world we live in. In most cases, their selection was a function of convenience paired with the image’s appropriateness for testing very specific software or hardware capabilities. For example, Greg Turk, who 3D-scanned the Stanford Bunny in 1994, bought it from a local Palo Alto home and garden supply store because the terra cotta material was “red and diffuse” and its geometry was not particularly complex7. The Lena photo was scanned because the engineers had been looking for an image of a face that was “glossy to ensure good output dynamic range,” and “just then, somebody happened to walk in with a recent issue of Playboy.”8

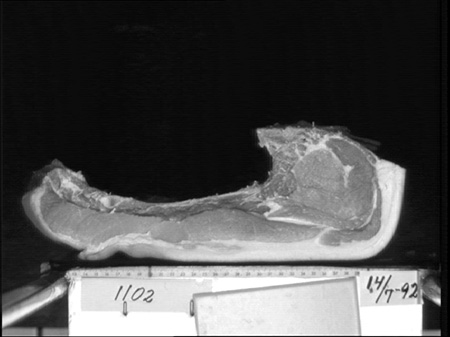

Image from a data set of meat photographs used in statistical shape analysis.

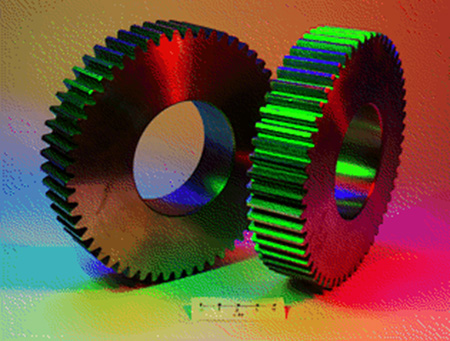

Image from ALOI database, a collection of 1,000 small objects recorded with systematically varied viewing angles, illumination angles, and illumination colors for each object

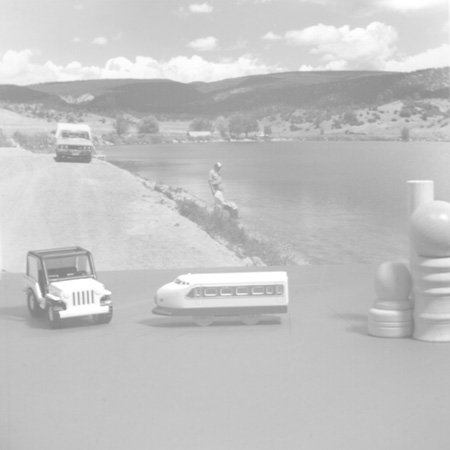

Image from a robotic vision training sequence animation (dead link), a frame from (I think) a setup used in training robots to recognize and remember visual background material

Image from hand sequence data set used in statistical shape analysis

Standard test image used for image analysis and computer vision testing

Image from a standard stereoscopic vision test set

These objects and images (and others like them) have a profound but hidden impact as the building blocks of an increasingly complex vocabulary of digital forms. As future developments in imaging technologies expand on their current capacities, these sorts of mundane archetypes will stay, at least metaphorically, ingrained at their basic levels. In the same way that the 19th century pop song “Daisy Bell” remained at the core of the “dying” HAL‘s regressing memory in 2001, the visual artifacts shown here will remain part of the evolutionary memory embedded in the methods machines use to process and describe visual information.

Image from a traffic sequence used in computer vision testing and modeling traffic behavior.

Synthetic lighting demonstration. 1992 demonstration of synthetic lighting technique used to accurately modify the lighting of a scene after it has been photographed. Lighting controls in the rendering of 3D models work according to these principles.

Image from machine vision test sequence. From a frame in a sequence used for image processing, image analysis, and machine vision research

Another Image from the ALOI 1,000 small objects database

- Hilary Berseth, email [↩]

- Turk, Greg, “The Stanford Bunny”, August 2000, Georgia Tech College of Computing, Atlanta, GA, <http://www-static.cc.gatech.edu/~turk/bunny/bunny.html> [↩]

- __________, “History of the Cornell Box”, , January 1998, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, [↩]

- Lindberg, Kelley J.P., “Pioneers on the Digital Frontiers”, Continuum: The Magazine of the University of Utah, Winter 06-07, The University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, [↩]

- Hutchinson, Jamie, “Culture, Communication, and an Information Age Madonna”, IEEE Professional Communication Society Newsletter, vol. 43, no. 3, May/June 2001, pp. 1, 5-7, Professional Communication Society of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, NY, NY [↩]

- ibid. [↩]

- Turk, Greg, “The Stanford Bunny”, August 2000, Georgia Tech College of Computing, Atlanta, GA, < http://www-static.cc.gatech.edu/~turk/bunny/bunny.html> [↩]

- Hutchinson, Jamie, “Culture, Communication, and an Information Age Madonna”, IEEE Professional Communication Society Newsletter, vol. 43, no. 3, May/June 2001, pp. 1, 5-7, Professional Communication Society of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, NY, NY [↩]

{ 18 comments }

I’ve loving this series. 😛

I’ve loving this series. 😛

Interesting essay, thank you. I posted some thoughts on it here:

http://www.tommoody.us/archives/2008/07/29/one-archetype/

Some questions for Kevin:

I see you are using these “archetypes” in your recent work. What is your response to this material? Do you like it? Hate it?

If these are the archetypes on which digital imaging culture is premised, is that good? Is that a question this essay and your artwork mean to be raising?

Best, Tom

Interesting essay, thank you. I posted some thoughts on it here:

http://www.tommoody.us/archives/2008/07/29/one-archetype/

Some questions for Kevin:

I see you are using these “archetypes” in your recent work. What is your response to this material? Do you like it? Hate it?

If these are the archetypes on which digital imaging culture is premised, is that good? Is that a question this essay and your artwork mean to be raising?

Best, Tom

At the Fraunhofer VR lab we used to test stuff with the 3D model of a cow. Especially awesome with a chrome surface. I will look what happened to her, i thought she was quite famous.

At the Fraunhofer VR lab we used to test stuff with the 3D model of a cow. Especially awesome with a chrome surface. I will look what happened to her, i thought she was quite famous.

Hi Tom, I really appreciate your thoughtful and impassioned response to the piece.

I don’t have great answers to your questions because they’re honestly not at the center of my engagement with this material, either in my work or in the essay. I haven’t given too much thought to whether I’m pro or con when it comes to the Stanford Bunny. It’s just a weird fact- funny, sad, obscure and maybe surprisingly consequential.

I “like” this stuff as subject matter in the sense that I’m fascinated by it. But I don’t feel qualified or obligated to judge whether it bodes well for the culture. I’m certainly aware of the mundane and pathetic qualities that my ‘archetypes’ possess. They make me think that if there were a ghost in the machine it might be that of Manet or Morandi or Edward Hopper. That was a funny idea for me when I first started looking at this stuff, but on reflection, it does accurately resonate with my emotional experience of the world (and the computer as part of that world). I think banality, mediocrity, boredom, etc., are important and underaddressed as subjects. They’re hard to make work about- you always run the risks of embodying what you’re talking about, appearing to advocate what you depict, or satisfying yourself with simple irony- but they are substantial parts of lived experience (mine, anyway).

So that’s my answer to the questions you pose here. There is one point in the post on your blog that I’d take issue with. I hope I’m not mischaracterizing your comments, but I think that to tie the source materials and tests I discussed above exclusively to the output of the likes of Pixar is an oversimplification. I share your view on most of those Hollywood products (which are usually geared, out of perceived economic necessity, to the lowest common denominator), but I think it’s an inaccurate generalization to say that “corporate teams rather than individuals are doing the experimenting” when it comes to the use of digital imaging technology. This may be true with the very cutting edge of expensive emerging technologies that require render farms and tens of thousands of animator-hours, but the material in my post has been used in the development of a wide array of tools, many of which have become useful to lots of good artists. I’m sure you’d agree that all artists who make use of Photoshop or a 3D platform (or just Jpegs) in any part of their process aren’t laboring in a “pre-Steiglitz” moment. These technologies have become commonplace- they’re part of the basic set of tools available to artists today, and the range of work that makes use of them is no more weighted to the bad than the range of work that makes use oil paint or film or clay.

As a side note, I’m not convinced that the problem with mass-market entertainment studios is necessarily rooted in the absence of an auteur mentality. I think there are other, thornier issues there, but that’s obviously a way bigger discussion.

Again, thanks so much for the thought-provoking response.

My best,

Kevin

Hi Tom, I really appreciate your thoughtful and impassioned response to the piece.

I don’t have great answers to your questions because they’re honestly not at the center of my engagement with this material, either in my work or in the essay. I haven’t given too much thought to whether I’m pro or con when it comes to the Stanford Bunny. It’s just a weird fact- funny, sad, obscure and maybe surprisingly consequential.

I “like” this stuff as subject matter in the sense that I’m fascinated by it. But I don’t feel qualified or obligated to judge whether it bodes well for the culture. I’m certainly aware of the mundane and pathetic qualities that my ‘archetypes’ possess. They make me think that if there were a ghost in the machine it might be that of Manet or Morandi or Edward Hopper. That was a funny idea for me when I first started looking at this stuff, but on reflection, it does accurately resonate with my emotional experience of the world (and the computer as part of that world). I think banality, mediocrity, boredom, etc., are important and underaddressed as subjects. They’re hard to make work about- you always run the risks of embodying what you’re talking about, appearing to advocate what you depict, or satisfying yourself with simple irony- but they are substantial parts of lived experience (mine, anyway).

So that’s my answer to the questions you pose here. There is one point in the post on your blog that I’d take issue with. I hope I’m not mischaracterizing your comments, but I think that to tie the source materials and tests I discussed above exclusively to the output of the likes of Pixar is an oversimplification. I share your view on most of those Hollywood products (which are usually geared, out of perceived economic necessity, to the lowest common denominator), but I think it’s an inaccurate generalization to say that “corporate teams rather than individuals are doing the experimenting” when it comes to the use of digital imaging technology. This may be true with the very cutting edge of expensive emerging technologies that require render farms and tens of thousands of animator-hours, but the material in my post has been used in the development of a wide array of tools, many of which have become useful to lots of good artists. I’m sure you’d agree that all artists who make use of Photoshop or a 3D platform (or just Jpegs) in any part of their process aren’t laboring in a “pre-Steiglitz” moment. These technologies have become commonplace- they’re part of the basic set of tools available to artists today, and the range of work that makes use of them is no more weighted to the bad than the range of work that makes use oil paint or film or clay.

As a side note, I’m not convinced that the problem with mass-market entertainment studios is necessarily rooted in the absence of an auteur mentality. I think there are other, thornier issues there, but that’s obviously a way bigger discussion.

Again, thanks so much for the thought-provoking response.

My best,

Kevin

Hi drx- I’ve seen the cow model around, but I omitted that and a lot of other well-known tests that didn’t have a real-world origin. If there’s an actual cow behind the model, I’d love to know about it.

My best,

Kevin

Hi drx- I’ve seen the cow model around, but I omitted that and a lot of other well-known tests that didn’t have a real-world origin. If there’s an actual cow behind the model, I’d love to know about it.

My best,

Kevin

Kevin,

Agreed that the auteur vs teams is a bigger discussion.

With Pixar movies (and many current ads and shorts that use that type of heavily rendered tech) there is a “look what we did this time” quality to each new film. In a sense they’re still doing their testing and that experimentation (and all the failure) is right up on the surface. So I don’t think we’re “there” yet. Although it’s probably too late to stop the digital puppet animation freight train–the box office is too solid.

Yes, there are artists working with Photoshop and these other tools but I believe they are getting good results as much in spite of as because of the means they are given (by corporate teams).

What I’m saying, I suppose, is perhaps engineers should ask artists’ advice before going out to the Pottery Barn to buy a new test object. It’s difficult to say whether our visual history might have been better if they had been doing that all along but I’m guessing it might have been more interesting.

Kevin,

Agreed that the auteur vs teams is a bigger discussion.

With Pixar movies (and many current ads and shorts that use that type of heavily rendered tech) there is a “look what we did this time” quality to each new film. In a sense they’re still doing their testing and that experimentation (and all the failure) is right up on the surface. So I don’t think we’re “there” yet. Although it’s probably too late to stop the digital puppet animation freight train–the box office is too solid.

Yes, there are artists working with Photoshop and these other tools but I believe they are getting good results as much in spite of as because of the means they are given (by corporate teams).

What I’m saying, I suppose, is perhaps engineers should ask artists’ advice before going out to the Pottery Barn to buy a new test object. It’s difficult to say whether our visual history might have been better if they had been doing that all along but I’m guessing it might have been more interesting.

Tom- I know what you mean about the movies and ads that embrace that 3D aesthetic (“rubbery horrorfests” was a great description). I just wanted to point out that the technologies we’re talking about have also been involved in the production of some very interesting painting, sculpture, photo, printmaking. This includes work where the role of the computer is small and unseen but crucial. (I do think that there’s even some good digital animation out there though it’s definitely still the exception.)

While I think I have a slightly more optimistic view than you do on the capacities and limitations of some software, I would agree (from lots of experience) that working in tension with the tools is often more productive than working to their strengths.

I agree wholeheartedly that artists should be consulted on the selection of test objects. But then again, I think artists should be consulted about more or less everything.

Tom- I know what you mean about the movies and ads that embrace that 3D aesthetic (“rubbery horrorfests” was a great description). I just wanted to point out that the technologies we’re talking about have also been involved in the production of some very interesting painting, sculpture, photo, printmaking. This includes work where the role of the computer is small and unseen but crucial. (I do think that there’s even some good digital animation out there though it’s definitely still the exception.)

While I think I have a slightly more optimistic view than you do on the capacities and limitations of some software, I would agree (from lots of experience) that working in tension with the tools is often more productive than working to their strengths.

I agree wholeheartedly that artists should be consulted on the selection of test objects. But then again, I think artists should be consulted about more or less everything.

Just in case anyone reading this gets the impression that I’m an antiquarian lover of the “touch” of art, I stopped doing conventional painting and drawing about 10 years ago and use only the computer to make work. But I still hate it. (Digital sound is a different story–I think it’s way ahead of visual technologies.)

Just in case anyone reading this gets the impression that I’m an antiquarian lover of the “touch” of art, I stopped doing conventional painting and drawing about 10 years ago and use only the computer to make work. But I still hate it. (Digital sound is a different story–I think it’s way ahead of visual technologies.)

THE BEAR IS THE GREATEST!!!

srsly hes just sitting there chilling out.

THE BEAR IS THE GREATEST!!!

srsly hes just sitting there chilling out.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }