POST BY PADDY JOHNSON

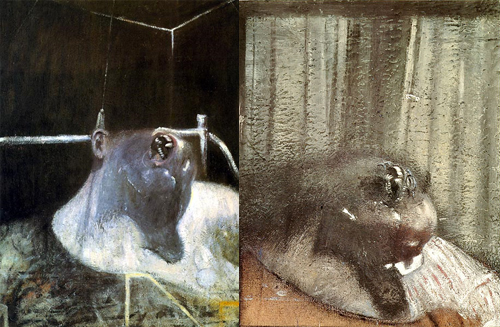

Francis Bacon, LEFT: Head I, 1947-48, Oil and tempera on board RIGHT: Head II, 1949, Oil on canvas

How many screaming teeth faces does a person have to see to get that painter Francis Bacon was interested in creating a psychologically disturbed, Godless space? Bacon critics will tell you one is more than enough (the work is a little didactic), but for me, it took the entirety of Bacon’s Centenary Retrospective at the Met to really understand his work. Up until this point, I’d only seen a few pieces in the permanent collections of the MoMA and Met, and hadn’t found they transcended their criticism.

Now traveling to the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, the exhibition provides a comprehensive and chronological arrangement of the artist’s best work. The first pieces a viewer sees were painted during the earliest stages of his career, each maintaining the freshness and exhilaration one might imagine present when the painter first began his work. A fair amount of scary faces and dark palettes fill these canvases — Head I, and Head II [above] amongst the most iconic — now oddly familiar as the imagery has so penetrated the cultural consciousness that we see it regularly in special effects film and television. As such, the exhibition takes on a slightly surreal feeling, with at least seven or eight still paintings palpably evoking the same anxiety of a thriller.

Francis Bacon, Three Studies for a Crucifixion, 1962, oil on canvas

Bacon’s work becomes more accomplished and effective as he gets older, though it also loses some of its youthful energy. We see a little less of the stripped disintegrating Pope figures, Study after Velazquez 1950 amongst them, which probably isn’t a bad thing. Even if Bacon was the only painter technically skilled enough in his time to pull off those works, his belief that life is transitory and without God is delivered without the complexity exhibited in some of his later work. Certainly Three Studies for a Crucifixion, 1962 [pictured above] a triptych depicting a murder scene and the 1961 painting in which the title describes the piece, Paralytic Child Walking on All Fours, present far stronger models of work made in that vein. Notably the painted treatment of both mature works exchanges the one to one relationship between translucent paint passages and meaning for flatter solid planes of color. The latter fields shape a psychological space with far greater success.

Probably amongst the most obvious evidence of Bacon’s mastery and innovation with paint can be seen in the way he melds photographic source material with abstract expressionism. Portrait of George Dyer Riding a Bicycle, 1966, is particularly effective in this vein, a single white brush stroke energetically applied as though it were a chain on his wheel.

As the catalogue tells it, Bacon’s paintings did not fit squarely into movements of the time, though he received accolades for his work almost immediately. Deemed a dogged figurative artist by American critic Clement Greenberg, his work was overshadowed throughout the dominant years of Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s. In his later years, he was associated with the 80s’ “revivial of painting,” though this work in the show was less impressive. Mirroring the countless self portraits the artist completed as he grew older, museum wall text endlessly reminds viewers that this was a result of outliving his friends and having no one left to paint. It’s a sad biographical note, and one that unfortunately speaks to the artist’s greatest weakness — a tendency to repeat himself. With this exception, however, the exhibition consistently showcases the painter’s best moments. And those highlights, skillfully arranged and hung at the Met, present a case even his staunchest critics may find hard to ignore.

{ 3 comments }

i was a huge bacon fan as an undergraduate, and this show was refreshing to see. yet, “the only painter technically skilled enough” and “mastery and innovation with paint” are exaggerations and gross distortions of why bacon’s paintings still resonate. his process –being ‘non-trained’– gives the work its vitality when it’s on, but i think to prop-up his skill set is to canonize him (uninterestingly) alongside some of the masters –like Velasquez– that he was freshly butchering through his painted fascination.

i was a huge bacon fan as an undergraduate, and this show was refreshing to see. yet, “the only painter technically skilled enough” and “mastery and innovation with paint” are exaggerations and gross distortions of why bacon’s paintings still resonate. his process –being ‘non-trained’– gives the work its vitality when it’s on, but i think to prop-up his skill set is to canonize him (uninterestingly) alongside some of the masters –like Velasquez– that he was freshly butchering through his painted fascination.

i was a huge bacon fan as an undergraduate, and this show was refreshing to see. yet, “the only painter technically skilled enough” and “mastery and innovation with paint” are exaggerations and gross distortions of why bacon’s paintings still resonate. his process –being ‘non-trained’– gives the work its vitality when it’s on, but i think to prop-up his skill set is to canonize him (uninterestingly) alongside some of the masters –like Velasquez– that he was freshly butchering through his painted fascination.

Comments on this entry are closed.