[Editor’s note: IMG MGMT is an annual image-based artist essay series. Slavs and Tatars is a faction of polemics and intimacies devoted to an area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China known as Eurasia. The collective’s work spans several media, disciplines, and a broad spectrum of cultural registers (high and low) focusing on an oft-forgotten sphere of influence between Slavs, Caucasians and Central Asians. They have had a number of international exhibitions in Moscow, Warsaw, Brussels, Berlin, New York, and Tbilisi. Currently they are preparing work for the Frieze Sculpture Park and Friendship of Nations: Polish Shi’ite Showbiz for the Sharjah Biennale, a look at the unlikely heritage between Poland and Iran. Their work is included in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Slavs and Tatars present Molla Nasreddin will be published by JRP/Christoph Keller in early 2011.]

We first came across the Azeri periodical Molla Nasreddin on a winter day in a second-hand bookstore near Maiden Tower in Baku, Azerbaijan. It was bibliophilia at first sight. Its size and weight, not to mention the print quality and bright colors, stood out suspiciously amongst the meeker and dusty variations of Soviet-style works in old man Elman’s place. We stared at Molla Nasreddin and it, like an improbable beauty, winked back.

Our book "Kidnapping Mountains" (above, cover) published by Book Works is a celebration of complexity in the Caucasus. The book was conceived as a research reader, in parallel to an eponymous exhibition at Netwerk Center for Contemporary Art in Aalst, Belgium. It's been with great pleasure that we have heard curators, artists, and laymen alike use it as a make-shift guide to the region.

Slavs & Tatars, “It's up to you, Baku,” Spread from Kidnapping Mountains (London: Book Works, 2009). This is one of three city-spreads, dedicated to the capitals of the Caucasian countries: namely, Baku (Azerbaijan), Yerevan (Armenia) and Tbilisi (Georgia) in the book: presenting an affective yet analytical approach to the cities

Slavs and Tatars, "Kidnapping Mountains," 2009; Installation view, Netwerk Center for Contemporary Art, Aalst, Belgium. For the exhibit, we built a highly geometric mountainscape of two of the highest peaks, Elbruz on the Russian side and Kazbek on the Georgian, in order to reference the dream-like romanticism and realpolitik of the region.

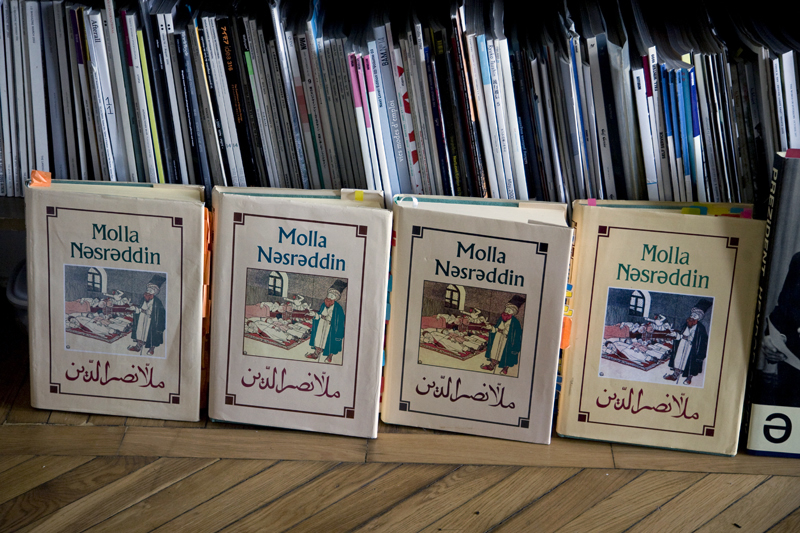

Recently reissued in its entirety, each volume of Molla Nasreddin runs 500+ pages, with a total of 8 imposing tomes in all. Since that blistering day several years ago, carrying and caring for these volumes between Brussels, Moscow, Paris, New York, Berlin, and Warsaw has toned our muscles if not our thoughts. Molla Nasreddin has become nothing less than a retroactive mascot of our artistic practice. The magazine’s pan-Caucasian identity (itinerant offices between Tbilisi, Baku and Tabriz), linguistic complexity (across three alphabets) and the use of humor as a disarming critique are also found across our work: as general inspiration for Kidnapping Mountains, our book with Book Works; in the strategic use of humor for our performance piece Hymns of No Resistance; or more literally in print editions such as Ahhhzeri.

A bit about Azerbaijan

During the two and a half decades of Molla Nasreddin’s run, the country at the heart of the magazine’s polemics and caricatures—Azerbaijan—changed hands and names three or four times, depending on one’s reading of history. Situated in the southern Caucasus mountains and bordering the Caspian sea, Azerbaijan sits squarely on the fault-line of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, with a population of some 9,000,000. Before 1991, Azerbaijan existed as an independent nation for a mere 23 months, sandwiched by a troika of Turks to its west, Persians to its south, and Russians to its north. Under Russian rule since the 19th century, Azerbaijan suffered much of the instability of its northern neighbor—the 1905 Revolution, World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917—as well as the short lived Azerbaijan Democratic Republic of 1918-1920 and the Bolshevik invasion of Baku in 1921. This period of furious upheaval in the Caucasus resulted in an equally frenzied creative intensity, especially with regards to the printed word.

Not only do the issues addressed in Molla Nasreddin remain as relevant today as when first published, so do the conditions and context surrounding the publication. Molla Nasreddin was not an underground publication or samizdat (self-published dissident edition), but an official magazine. Following the Tsar’s decree of 17 October 1905, which allowed more press freedoms, publications of all political breeds and behavior thrived. [1] Yet none were comparable either in influence, circulation or geographic reach to Molla Nasreddin.

Paper, politics, process

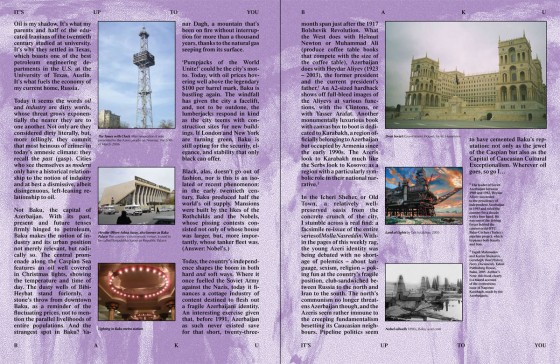

Caption: "Bridge" Molla Nasreddin, the magazine, uses the legendary figure of Molla Nasreddin, the man in the spotted hat, a satirical Sufi figure whose tales and anecdotes are found from Croatia all the way to China, as a mascot. Somewhat akin to Aesop's fables, his pithy folk wisdom is timeless. The body with the prayer beads belongs to a mullah who is walking across the heads of Azeri men.

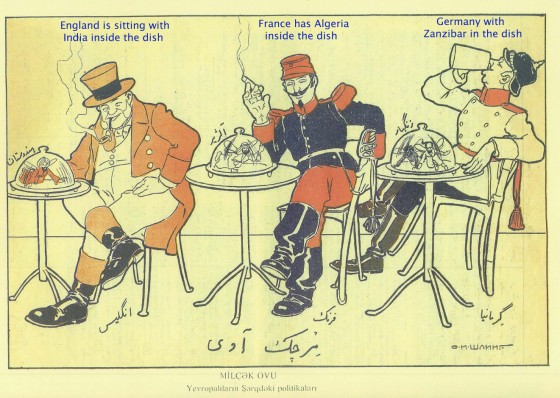

Published between 1906 and 1930, Molla Nasreddin was a satirical Azeri periodical edited by satirist and writer Jalil Mammadguluzadeh and named after the legendary Sufi wise man-cum-fool of the middle ages. Using acerbic humor and realist illustrations reminiscent of a Caucasian Honoré Daumier, Molla Nasreddin attacked the hypocrisy of the Muslim clergy, the colonial policies of the US and European nations towards the rest of the world, the venal corruption of the local elite, and argued the importance of education and equal rights for women. The magazine was an instant success, selling half its initial print run of 1000 on its first day. Within months it would reach a record-breaking circulation of approximately 5000, becoming the most influential and perhaps first publication of its kind to be read across the Muslim world, from Morocco to India. [2]

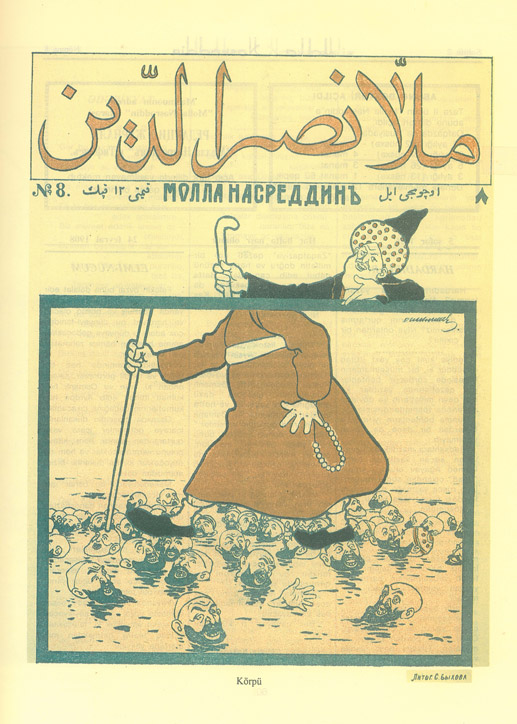

Caption: "The Balkan Question." Throughout the magazine's run, animals are often used as stand-ins for countries. The use of animals as protagonists is a common feature to both Russian and Slavic folklore, on one hand, and Persian/Turkish literature on the other, due to the ban on figuration in the Qu'ran. Unlike other animals, the symbol for Russia, the bear, is never explicitly identified because Molla Nasreddin had to receive approval from the official state censors of Imperial Russia in order to publish.

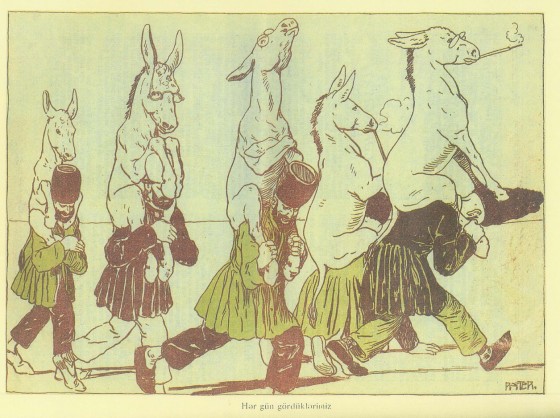

Caption: "What we see everyday." The world is upside down: the donkeys are being carried by the people. Visible from their glasses and pipes, the donkeys here are the rulers. An ascerbic critique of the ruling clerical class, the caricature hints that the Azeris are following people that they should instead be leading.

Even though the publication acted as a rallying cry of sorts for the nascent Azeri nation, Molla Nasreddin‘s non-conformism and independence were also a result of the city where it was first published, Tbilisi, the present day capital of neighboring Georgia.

When Mammadguluzadeh received an official permit to publish the weekly, Tbilisi was the capital of Transcaucasia. Comprising present day Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, Transcaucasia was a hotbed of liberalism. All types of socialists lived there, from young aristocrats à la Decembrists sympathetic to the tide of social revolution sweeping Europe, to narodniks, late 19th century Russian middle-class populists, and followers of different sects. Tbilisi was a polyglot city with a significant Muslim population looking culturally to Iran, linguistically to Turkey, and politically to Moscow.

An unlikely platform for Women’s Rights

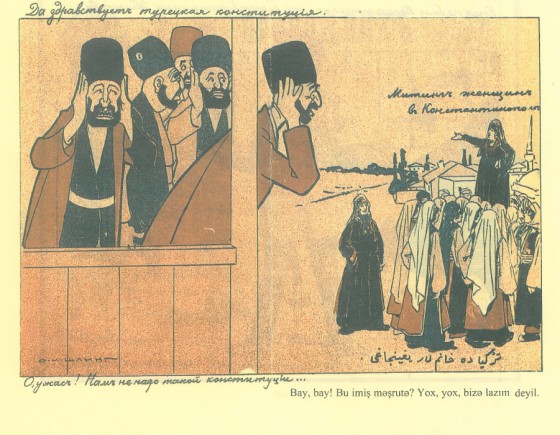

Text: (top left) "Welcome the Turkish constitution."; (right) "Women at a meeting in Constantinople." Caption: "Horror! We don't need this kind of constitution."

Of the recurring themes in Molla Nasreddin, two in particular set the weekly apart from the number of satirical publications of the early 20th century: the advocation of women’s rights and the Azeri elite’s snobbery towards its own culture. In one illustration (above), the very advocates of the constitution balk when they learn that the document also empowers women, who have begun to gather around a speaker.

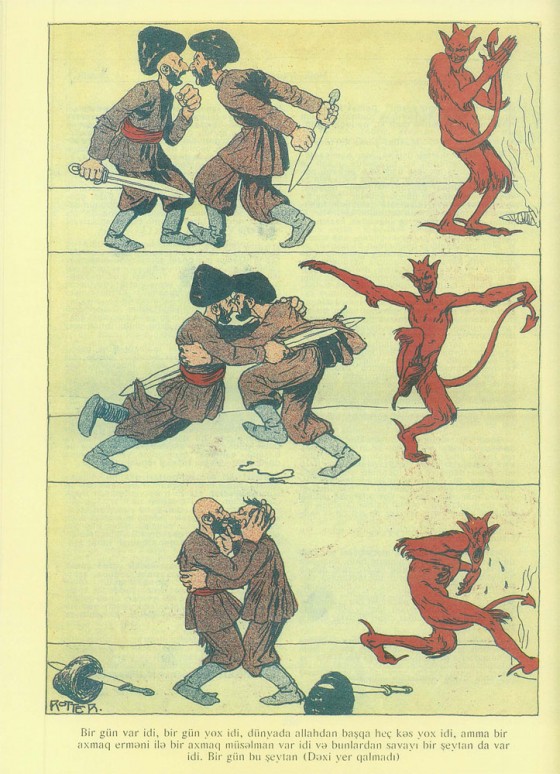

Caption: "There was no one except Allah. And then a stupid Azeri, an idiotic Armenian, and except for them, there was one devil. And one day, the devil”¦" Armenian-Azeri relations have been dismal for centuries, as is visible today in the frozen conflict of Nagorno-Karabakh, a region in the Southern Caucasus officially recognized as belonging to Azerbaijan, but under de-facto independence following the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the late 1980s. The man with hair (R) is Armenian and the bald man (L) is Azeri.

Women’s rights often act as a prism through which most other issues are addressed. Several illustrations stress the need for women’s education and point to Armenian literacy and modern educational system as the example to follow, a particularly potent counterpoint given the historic enmity between the Azeris and Armenians, who represented the most visible Christian population. Much like the advocation of women’s rights, the use of Armenian examples allows the weekly to further criticize the hypocrisy and fanaticism of the Muslim clerics and establishment.

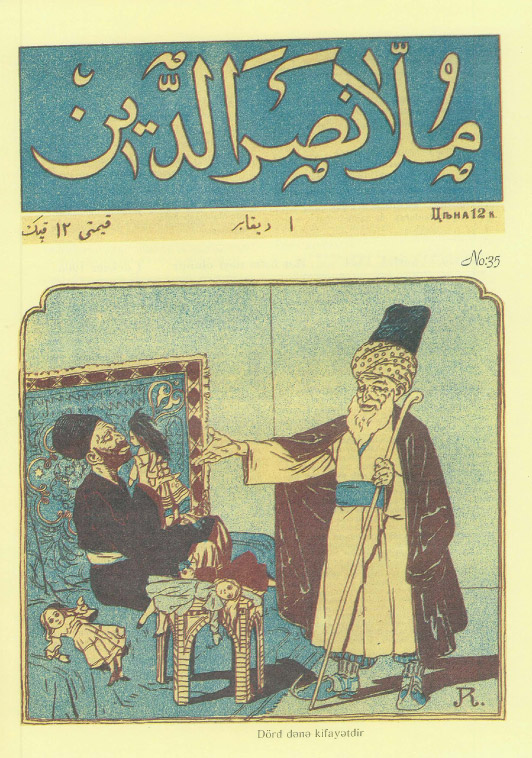

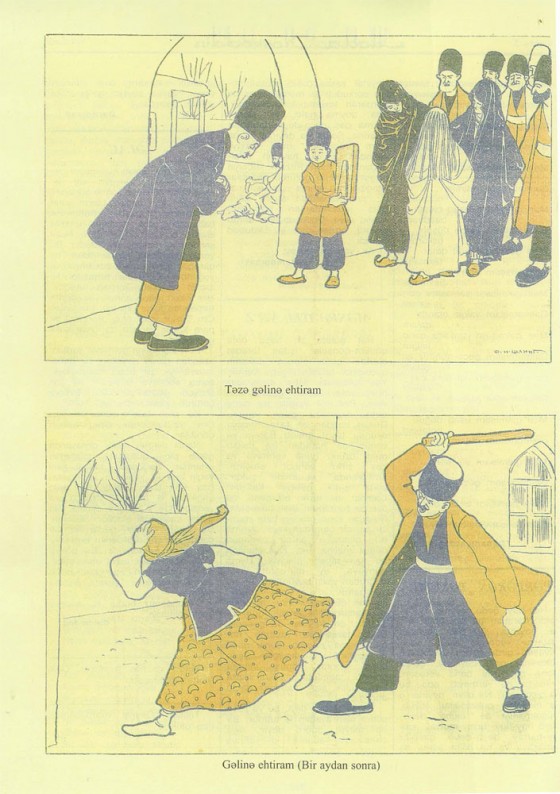

In its fight for equal rights for women, Molla Nasreddin rails against the oppressive effects of polygamy, pokes fun at parents’ preference for a son over a daughter and exposes the double standard of Azeri men towards Azeri women. Azeri Muslims who insist on piety for their female counterparts have no issue frolicking with European women when traveling. One cover illustration even depicts men drafting a letter to the local governor asking for a public brothel.

Caption: "A letter from Tbilisi Muslims to the local government in support of opening a public house (brothel) in the Muslim quarter."

Molla Nasreddin‘s proto-feminism takes place against a rather unexpected backdrop of similar initiatives in Azerbaijan and the greater region. Along with Crimean Tatar Ismail Gasprinsky (1851 — 1914) and his journal Tercüman, Mammadguluzadeh and Molla Nasreddin were key figures in the Jadid (meaning “new” in Arabic) movement. During the Jadid movement, Muslim reformers in late 19th century Russia enacted progressive educational reforms, ranging from the tactical introduction of benches, desks and maps into classrooms to more substantial initiatives such as opening girls’ schools and drafting new textbooks. These reforms culminated in Azerbaijan’s short stint of independence as the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic from 1918-1920, during which suffrage was extended to women for the first time in a Muslim nation. To this day, Azeris take pride in granting all women the right to vote well before such countries as the US (1920) or UK (1928).

The Wise Fool and the Alphabet that Fools Around

Molla Nasreddin saw the latinization of Azeri as a key point in its progressive agenda. With three changes to the Azeri alphabet in less than 70 years—from Arabic to Latin in 1929, Latin to Cyrillic in 1939 and Cyrillic back to Latin in 1991—its history has polyglots around the world stumped as to whether to blush, laugh or cry. Calling it “the revolution of the East,” Lenin required all the Turkic speaking peoples of the Soviet Union to Latinize their alphabets. 10 years later, though, Stalin thought otherwise and changed their alphabets to Cyrillic in 1939 for fear that the Turkic peoples of the USSR might get too close to the West. On the pages of Molla Nasreddin, one comes across all three scripts, adding extra work to the already daunting task of translation. It is one thing to find a translator for a language spoken by four million people, but another thing entirely for that translator to also know the two previous iterations of his/her own language.

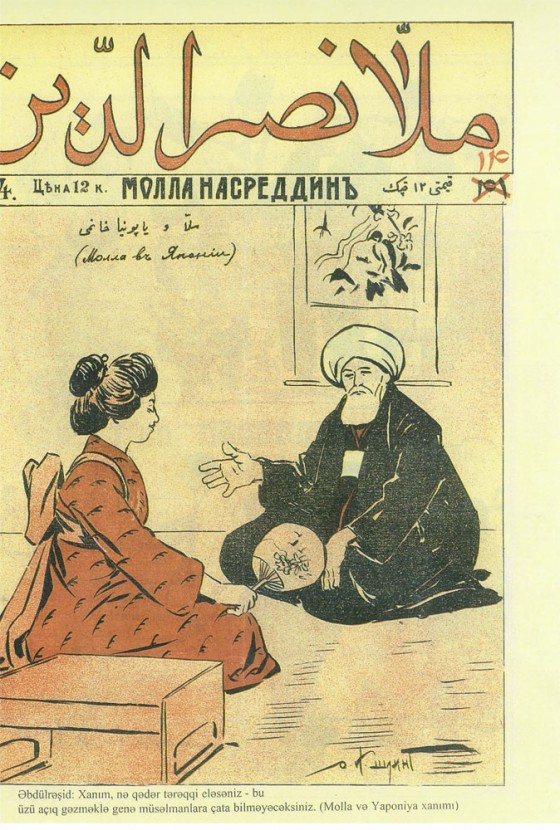

Caption: "Dear lady, no matter how much progress you make, as long as your face is uncovered, you don't even compare with a Muslim woman."

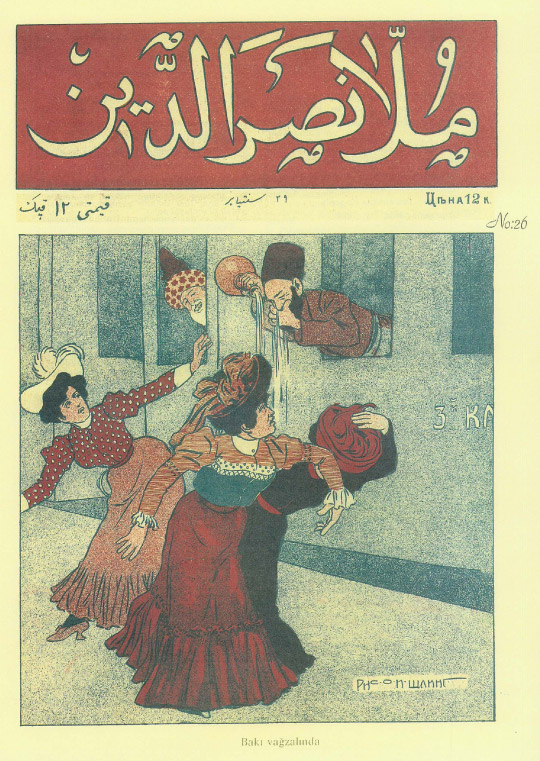

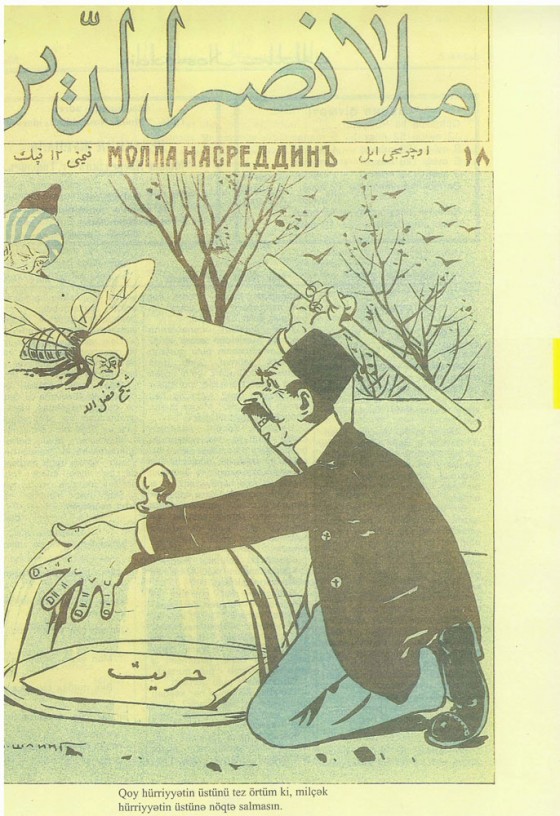

The covers of the magazine (such as the one above) are a perfect demonstration of this linguistic schizophrenia. On a single page there are three scripts: the original title is in Arabic, underneath is in Cyrillic, and on the very bottom the caption is in Latin.

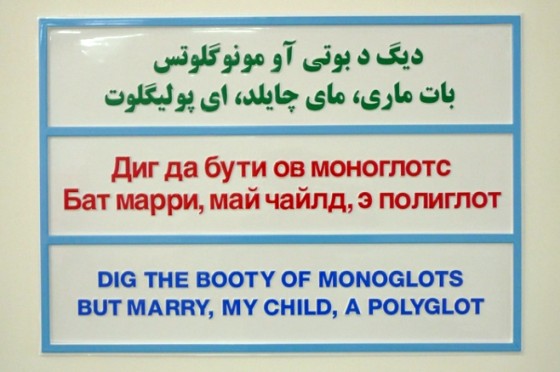

Slavs and Tatars, "Dig the booty”¦," 2009, Vacuum-formed plastic "Dig the booty”¦" was one of two pieces conceived in homage to the devastating changes of the Azeri alphabet. Transliteration—converting text from one alphabet to another, say from a non-Latin alphabet to the Latin one used by English—is to some extent the black sheep of language and linguistics: it's considered cheap, uneducated and almost dirty. Yet it remains a necessary practice to deciphering foreign languages. Dig the Booty”¦ demonstrates the collision or mash-up of two very different registers of language: a kind of solemn erudition on one hand and raw street slang on the other.

Горе от Ума (Gore ot Uma), wall painting, 180 x 200 cm, for "Ruins of Our Times," Ministry of Transport, Tbilisi, Georgia, 2010. Горе от Ума is a famous 19th-century play about Moscow manners by Aleksander Griboyedov, a close friend of Pushkin's and diplomat to the Czar in the Caucasus. The play is translated in English as WOE FROM WIT or THE MISFORTUNE OF BEING INTELLIGENT. By changing the Е in the original Russian title to an Ы,the title changes to MOUNTAINS OF WIT and the urban premise of the original work is hijacked by an imaginative Caucasian setting, one which played an influential role in Griboyedov's life and death.

These problems pale in comparison to the tragic loss such ruptures in linguistic continuity cause for generations of Azeris, past, present and future. The changes in the alphabet essentially made Azeris immigrants in their own country, separating them from their own cultural legacy and past generations. Grandparents, parents, and children could speak the same language but could not read the same books. After the 1929 diktat where Moscow decided to Latinize the Azeri alphabet, books in Arabic were immediately destroyed, resulting in the disappearance of many texts, including an important body of work on Islamic natural medicine. The linguistic disruptions of the 20th century are still wreaking their havoc. Though Azerbaijan has far more economic strength than its neighbors (Armenia and Georgia) due to oil, the country suffers from a less coherent national identity. The inclusion of all three alphabets throughout Molla Nasreddin demonstrates the defeatism of the current publishers: unable to choose between authenticity and reform, they opt for a muddled, middle way.

Nascent nationalism and innocent independence

Caption: "Baku train station." According to an old Azeri superstition, when one is setting out on a journey, it is considered good luck to pour water behind oneself. An Azeri man here pours water onto the platforms to the shock and dismay of European women, a clear parody of the clash of cultures (European and Asian) and classes in the Caucasus at the turn of the century.

Although today the term nationalism has a reactionary ring to it, a century ago it allowed countries with uncertain pasts and even less certain futures to carve out a national identity thus far ignored, suppressed or simply forgotten. Straddling the frontier between Europe and Asia, West and East, Azerbaijan’s precarious geopolitical stature was not for wont of such nationalists, the most prominent being Mammad Emin Resulzade (1884-1955), the scholar and political leader of the short-lived Azerbaijan Republic. Their ultimate objective was Azeri independence, but these goals are achieved one step at a time. Molla Nasreddin focused on the assessment and appreciation of Azeri culture in its own right to put it on equal footing with the cultures of the larger surrounding nation states (Russia, Persia, Turkey.)

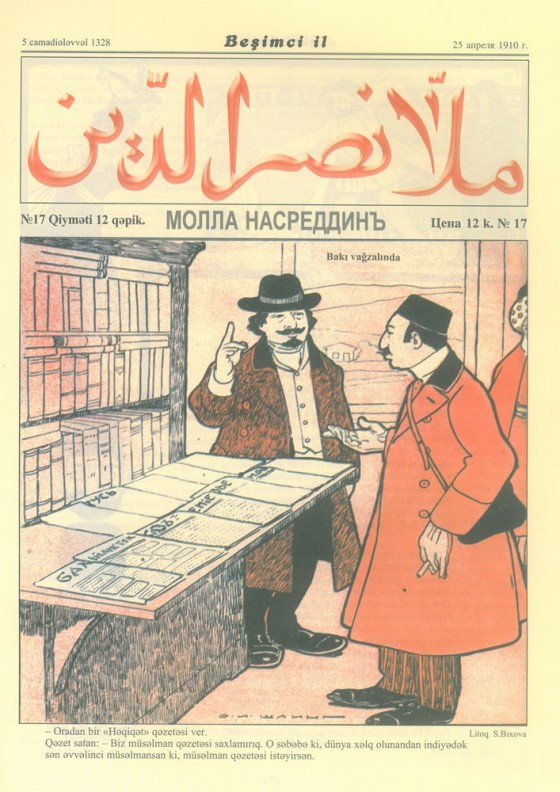

TOP: Baku Train Station; Client: "Do you have Haqiqat newspaper?" Salesperson: "We don't have any Muslim papers. For the following reason: since the creation of the world, you are the first person to ever ask for a Muslim paper."

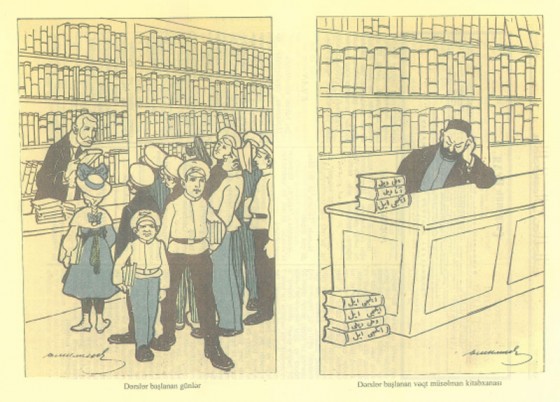

Illustrations, announcements, and mock telegrams in MN parody the European clothes that the Azeri elite wear, often taking aim at the self-styled intellectuals who go to great lengths to differentiate themselves from their more common compatriots. Whether they lived in Moscow, Tbilisi or Baku, the Azeri elite read, wrote, and spoke amongst themselves in Russian. After all, Russian was considered literary, elegant, and edifying, whereas Azeri (called Turk) was seen as vulgar and uneducated. This concept is demonstrated in the illustration below that contrasts the hustle and bustle of the beginning of the school year at a Russian school with the sleepy calm at an Azeri (i.e. Muslim) school.

Caption: L: "The beginning of courses (in a Russian school)."; R: The beginning of courses in a Muslim library."

Molla Nasreddin’s relevance today

Caption: "Let me cover freedom faster so that no flies sit on it" (On the plate is written Hurriyet (Freedom). The fly represents Sheikh Fazlollah. With every notable event in Iran being featured in some capacity in the weekly, Iran was arguably the country where the magazine had its largest impact. Via its relentless focus on the Iranian rulers' inefficacy, MN's essays acted as a preamble of sorts to the Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1906-1910 resulting in the establishment of the first parliament in all of Asia.

By 1920, the Soviets had invaded Baku and Azerbaijan’s independence came to an end. The quality of Molla Nasreddin‘s editorial and art-direction suffered considerably as the periodical was forced to tow the Bolshevik party line. Moscow shoved editorial directives down Mammaguluzadeh’s throat, destroying its independent streak, even going so far as to ask to change the magazine’s name to Allahsiz (The Atheist). Only three issues of Molla Nasreddin came out in 1931 and shortly afterward shut its doors for good. Its impact, however, is difficult to over-estimate. Just across the border in Iran, the magazine was lionized and copied by the very people who led the Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1906-1910, the first parliament established in Asia.

Through a mix of buying the people’s sympathy and strict autocracy, Baku has successfully handled the major geopolitical issues of the 20th and early 21st century—Bolshevist Communism from Russia or fundamentalist Islam from Iran. While the region might first appear remote to Western eyes, the Caucasus remains relevant today for several reasons such as the residual proxy wars between the US and Russia in neighboring Georgia, or the line of suitors (US, Russia, Turkey, Iran or China) vying for access to the oil-rich Caspian. If we are to believe the faulty theory that the West and Islam are on a collision course, we would do well to look at the only precedent in history where the ideas of both co-existed, in the Caucasus and across Eurasia. Azerbaijan’s progressive history and geographic position between Europe and Asia offer the potential for a revolutionary moderate Islam where pluralism and politics are not mutually exclusive. The debates at the heart of Molla Nasreddin—Islam’s confrontation with modernity, Imperial over-reach, corruption—have only become more pressing and immediate over the last half century, whether you are in Alaska, Angola or Afghanistan.

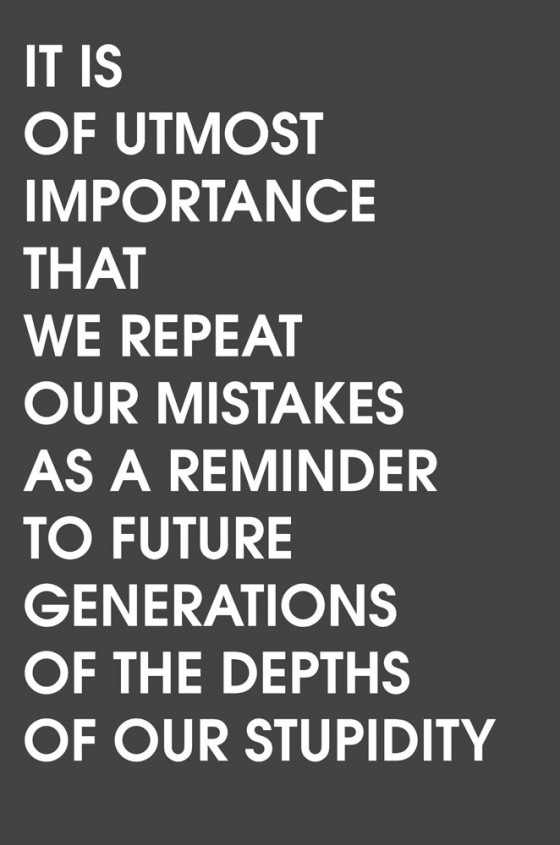

Slavs and Tatars, "Stupidity," (from the Wrong and Strong series) 2005, off-set. The above piece is an example of a particularly Slavic sense of defeatism, or gallows humor, that Slavs and Tatars shares with Molla Nasreddin, the figure and the magazine: the first half of the phrase collapses in the end, with the punch line.

The complexity of the Caucasus and the sharp, aphoristic humor of Molla Nasreddin continue to inspire our practice, from polemics to poetics to print. On many occasions, we have been asked why we do not intervene within the pages of the periodical, like the Chapman Brothers did with Goya. If Slavs and Tatars are artists, why only translate and re-print? The answer points to the very inception of our collective: part of our work has always been and remains preservation and distribution of relevant ephemera that is inaccessible or overlooked. In this sense, the success of Molla Nasreddin brings us back to the common American Conservative aphorism: If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

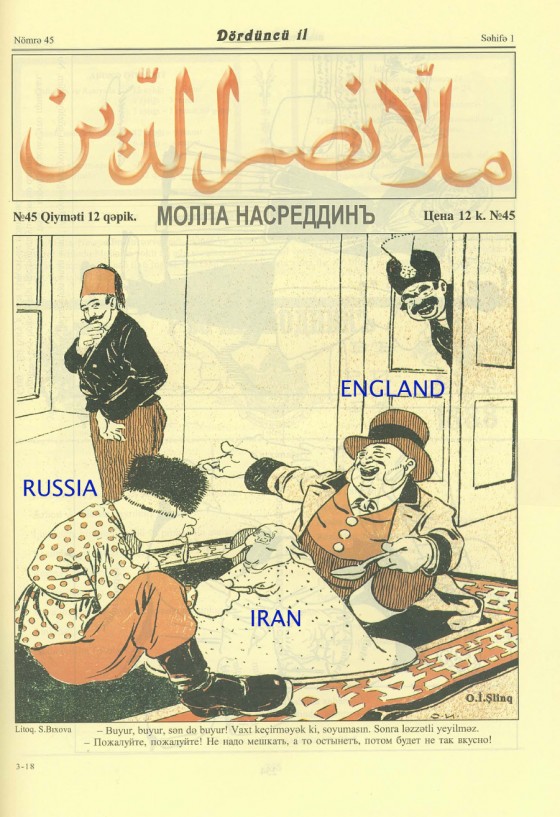

Caption: "Please please, no need to hesitate. Otherwise it will get cold and won't be as delicious!"

[1] Bennigsen, Alexander. “Mollah Nasreddin et la presse satirique musulmane de Russie avant 1917,” Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique, Vol 3, Nº3, 1962.

[2] To put these figures in perspective, the top papers in circulation today in Azerbaijan have an approximate print run of 25,000 for a population of 9 million. During the time of its publication, Azerbaijan had a population of roughly 2.5 million of which it is safe to say that a far smaller percentage was literate.

{ 10 comments }

I visited the Caucasus in 1981 before the fall of communism, I was fascinated by the fact I could see mount Ararat in turkey, the place where Noah supposedly landed his ark, also for a time escaping state controlled Russia into this strange region with its almost gypsy identity. After reading this article, l now see the region with a language on every facet of each mountain

I visited the Caucasus in 1981 before the fall of communism, I was fascinated by the fact I could see mount Ararat in turkey, the place where Noah supposedly landed his ark, also for a time escaping state controlled Russia into this strange region with its almost gypsy identity. After reading this article, l now see the region with a language on every facet of each mountain

I visited the Caucasus in 1981 before the fall of communism, I was fascinated by the fact I could see mount Ararat in turkey, the place where Noah supposedly landed his ark, also for a time escaping state controlled Russia into this strange region with its almost gypsy identity. After reading this article, l now see the region with a language on every facet of each mountain

I visited the Caucasus in 1981 before the fall of communism, I was fascinated by the fact I could see mount Ararat in turkey, the place where Noah supposedly landed his ark, also for a time escaping state controlled Russia into this strange region with its almost gypsy identity. After reading this article, l now see the region with a language on every facet of each mountain

I visited the Caucasus in 1981 before the fall of communism, I was fascinated by the fact I could see mount Ararat in turkey, the place where Noah supposedly landed his ark, also for a time escaping state controlled Russia into this strange region with its almost gypsy identity. After reading this article, l now see the region with a language on every facet of each mountain

I visited the Caucasus in 1981 before the fall of communism, I was fascinated by the fact I could see mount Ararat in turkey, the place where Noah supposedly landed his ark, also for a time escaping state controlled Russia into this strange region with its almost gypsy identity. After reading this article, l now see the region with a language on every facet of each mountain

I visited the Caucasus in 1981 before the fall of communism, I was fascinated by the fact I could see mount Ararat in turkey, the place where Noah supposedly landed his ark, also for a time escaping state controlled Russia into this strange region with its almost gypsy identity. After reading this article, l now see the region with a language on every facet of each mountain

Well you can see it from Armenia too… -.-‘

And it should’ve been from Armenia you saw it.

Thanks very much for this hugely informative article. I have requested the collection you have compiled, from a library, and can’t wait to see it. I am just curious if you might know whether all the collections of Molla Nasreddin may be found in English translation?

In the issue devoted to the Balkan Issue, the fox marked ‘Austria’ has a chunk of meat in its mouth. The original Arabic script identifies the chunk of meat as Bosnia (Bosna), not Bulgaria.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }