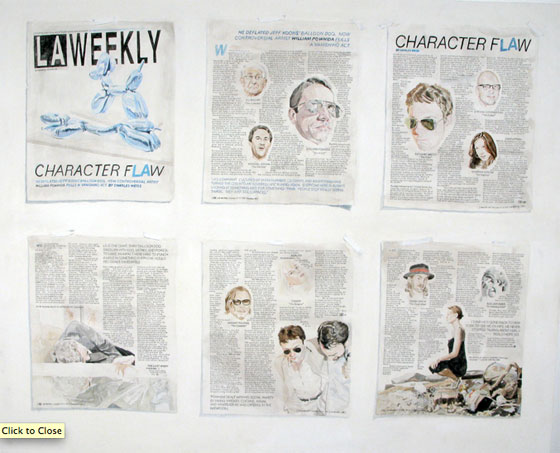

William Powhida, from the series No One Here Gets Out Alive, 2009

Editors note: I have a feature running in this month’s issue of Map Magazine on what it means to survive in New York. The article won't be online until the end of the month, but in the meantime I will be posting interview excerpts that didn't make it into the piece. The second interview in this series is with artist William Powhida. The first was with Shelly Bancroft and Peter Nesbett of Triple Candie, a non-profit gallery located in Harlem.

Paddy Johnson: How do you get by in the City? Is there a specific story to how you got started, and your career path?

William Powhida: The first thing is that I’ve had a day job the entire time I’ve been in New York. I teach high school, that goes back to being in graduate school. For the first year, at Hunter, I was working at a catering company just to pay the bills; this was the Fall of ’98. It was $600 a month for a… I wouldn’t even call it a one-bedroom. It was a tiny backhouse in Williamsburg, like a berth on a ship (Related: actual shack for rent on craigslist). The shower was next to the sink. A lot of artists have roommates, but I didn’t know anyone. After that first year I realized I needed a job to support me. I ended up getting a teaching job and becoming a licensed, certified teacher over the next few years; at the time you could get a job in a public school while working your way through the certification process. It was really difficult, the first five or six years, trying to support myself, but I sacrificed a bit of my living situation in order to afford a modest studio for $200-300 a month. Once I was able to start selling a little bit of artwork, I thought I’d be able to go part-time, but the matter of actually selling the work and collecting the money turned out to be much more of a challenge.

PJ: Did you have any free time? What did you do to relax? Was it possible?

WP: (Laughs) Not really. I was working from eight to three at the school, and then rushing to classes, staying up too late on the weekends trying to cram in whatever social life I could find. It was all art all the time, and teaching art in the school – obviously there’s a cultural difference there, but they were both very creative outlets. The day job wasn’t just something to make money to support the practice. When I got out of grad school, I felt like I had an incredible amount of time on my hands, and I was trying to figure out what kind of art I was going to be making. I wanted to continue the sort of dialog that was happening in graduate school; I got out, and there wasn’t the same kind of conversation about art. So I started writing for a couple small blogs, like FREEWilliamsburg, and through that process started writing at the Brooklyn Rail, and suddenly I found myself spending my weekends looking at art, and writing about it as well, and trying to make art happen. I think I spent the better part of three years trying to make work, so that the critical practice gave way to the art-making practice in 2005, 2006.

PJ: This doesn’t sound so different from what I’ve done, or what my friends have done, in terms of the amount of work that goes into creating a viable practice. Has that struggle helped, or hindered, your work?

WP: I think it helped it far more than it hindered it. At a certain point, the art has to do something, whether that means selling or addressing the pressures that I was constantly under. I didn’t have the time or the money to develop something that didn’t in some way address something in my life. I’ve seen a lot of artists give up, feeling they’re not being recognized. Working as a critic, developing relationships with art dealers and other artists, was really helpful in creating some opportunities for access. When the work became relevant to more than my own personal narrative, it opened up into a dialog about being an artist; my experiences could be fodder, but so could all the other experiences that other artists were having. It [the struggle] was really starting to inform the work. So I wish it could have been easier, but I don’t think I would be making the work that I’m making. The notion of getting by in New York, how can I pay my rent, how can I eat, how can I afford to go out- honestly, there are a lot of feelings of… I wouldn’t say shame, but-

PJ: I do think there is an element of shame, as you get older. New York is very career-obsessed.

WP: The career pressures can be really brutal, and it becomes a limiting factor in the art world. People talk about a war of attrition, that you just have to hang on long enough, but you also have to experience other people’s success, and other people’s career paths, and negotiate those. In my case, it fed into my work, so it didn’t become something that wasn’t spoken about or addressed in some way, but it could be something as small as still having roommates in your thirties, or the neighborhood you live in. So much of the art world, there’re strata there, and it’s sometimes hard to meet all those demands. It creates a sense of desperation, and that can either really hurt somebody’s career, make it really difficult to keep trying, or it can maybe become a motivator. I have a lot of artist peers who are still struggling, who would just like to have a solo show at a commercial gallery.

PJ: Well, it gets harder as you get older, right?

WP: Yeah, because there’s so much emphasis on youth, and coolness, and it doesn’t hurt to be tall and handsome. These are uncontrollable factors that become intangible pressures on the artist, outside of how your CV looks or what reviews you’ve gotten. There’s nothing like sitting in a gallery and feeling like a failure because you didn’t get any press; that’s to say nothing of sales or museum placement.

PJ: Is there anything else you want to add?

WP: One thing that other people might want to hear, or understand: being a moderately successful artist, or becoming an emerging artist, it’s not like you’ve won some lotto and somebody sends you a check to cover your expenses. It’s really hard, still, to even stay afloat financially, run a functional studio, and be a businessperson. This is all learning on the fly, and it’s a real challenge.

PJ: To what degree do you feel like you’re running a business?

WP: Now, it’s taking up maybe 25% of my studio time, whether it’s responding to press requests, or supplying the gallery with information, or trying to get paid. Once you get past the hurdle of exhibiting, and getting someone to buy the work, it just creates more and more responsibilities. If you can’t make enough money to free up more time, it crunches down the time you have to actually be working in the studio.

{ 7 comments }

Bill, I hope you were paid for this. Blogs are supported by slaves and you’re one of them. She’ll collect ad royalties for life but where are yours?

Is the issue here that artists don’t get paid for interviews that appear in press? The New York Times doesn’t pay The President when they interview him, so I’m not sure why I need to buck the industry trend for Mr. Powhida. I agree people don’t get paid enough in the arts, and that yes, a lot of free writing appears on blogs, but the complaint your lodging doesn’t make any sense.

Please respond to the substance of the post or further comments will not be approved.

What artist expects to be paid for an interview? Most are honored to have a chance to explain what they’re about. Powhida says press is part of his business, blogs are press, why the extreme moralizing? “Slaves,” such melodrama.

What a lovely and earnest interview. Thank you Paddy. It sounds as though Bill is gearing up to win that war of attrition. I think you should have asked him straight up whether he was going to survive. No more softballs!

So is he still teaching school and working a day job? If so, that’s pretty disheartening. After all, he’s fairly well known and extremely talented. Anyway, great interview. I appreciate his candidness. Thanks.

BOO HOO!!!! WAAAAHHHHHHH!!!!!! it’s sooo hard out there. let me go get you a cup of cocoa and a blankie. i like powhida’s alter ego better. where was he? he’s always positive, taking over the world and the life of the party – and he gives a more entertaining interview.

but i’m just jealous.

i think the title of the series “survival” in new york automatically puts the subject into the “tales of hardship” mode, and can make them come off as kind of whiny. so maybe it’s not william’s fault. either way, i’m a big fan of both of them.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 4 trackbacks }