Despite the occasional mad rant or impromptu bathing session, riding the MTA today is generally a much tamer prospect than it was in 1980, when Bruce Davidson began documenting the trains and its passengers. Those efforts resulted in the 1986 monograph Subway, celebrated as a frank depiction of a unique and perhaps infamous moment in New York's history. A third and final edition of the book is now available, and to mark its release, the Aperture Foundation gallery has a selection of prints on view. While the work ultimately contributes little to the conversations driving art photography today, it nonetheless stands as an anomaly in both Davidson's work and the longstanding tradition of subway photography, and as such warrants some discussion.

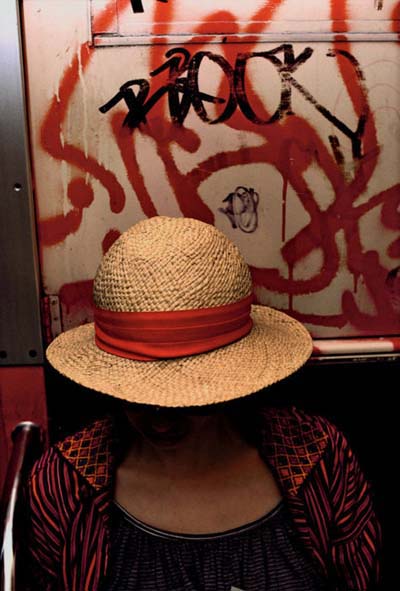

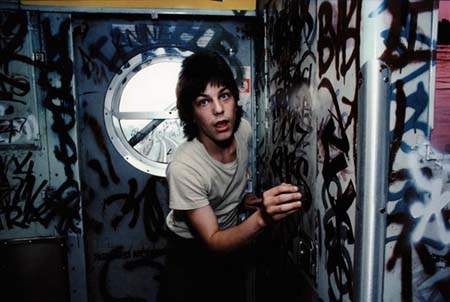

Subway is mainly famous for capturing a dirty and dangerous period in NYC's history. To be sure, grittiness plays an important role in the work: Davidson's subway is an overheated, overcrowded, and potentially violent setting for gunpoint muggings, drug-related medical emergencies, and numerous instances of vagrant nudity. In viewing the series, though, it seems clear that what truly interested the artist was not the unkind conditions, but rather the people who converged on the subway each day and endured them. Davidson writes in his essay, “I wanted to transform the subway from its dark, degrading, and impersonal reality into images that open up our experience again to the color, sensuality, and vitality of the individual souls that ride it each day.” Conceptually, this is familiar territory for Davidson, who used the same basic approach to portraiture in Brooklyn Gangs and 100 East Harlem. Aesthetically, however, Subway represents a noteworthy departure, as he momentarily abandons his signature black-and-white imagery in favor of vivid color snapshots. This new palette introduces a graphic sensibility otherwise unseen in his documentary work, one which Davidson uses to capture more vividly the darkness and the sensuality he observed. Depicted in black-and-white, for instance, the trains' layers of graffiti would register as merely oppressive; rendered in color, however, the tags interact with passengers' clothes and skin tones, creating striking visual dialogues. Equally purposeful is Davidson's use of a strobe flash, which helped him achieve deep blacks and blown-out hues that amplify the subway's violence. By adding color, Davidson transformed his subway rides into aesthetic experiences, revealing a visual lushness that might otherwise be overlooked, and the resulting photographs are unique in his body of work.

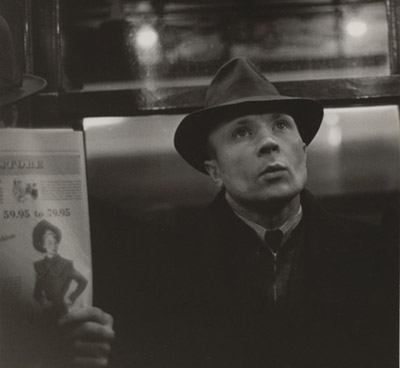

It's worth pointing out that in choosing the transit system as his setting, Davidson joined a longstanding tradition of subway photography, one that includes such notables as Walker Evans, Wolfgang Tilmanns, and Chris Marker. The subway is an attractive setting to documentary photographers because of its unique voyeuristic potential: it's an unpredictable, anonymous, and enclosed environment containing a diverse range of subjects who, despite the public setting, often remain lost in their own inner worlds. For most subway photographers, remaining unnoticed by their subjects is a crucial part of the process, as it allows them to capture candid portraits free of projections or self-awareness. A prime example of this approach would be Evans' 1930s NYC subway shots, eventually released under the title Many Are Called. To remain covert, Evans used a miniature camera hidden in his coat, capturing his fellow riders lost in moments of boredom or reverie.

Davidson's method breaks from this convention. He deliberately made his presence known by carrying his camera around his neck, and when a subject or scene caught his attention, he would approach people, explain his project and ask their permission to shoot. If they agreed, he would ask them either to look directly at the camera or to return to the activity or stance that had interested him. His approach yields entirely different results from the typical stealth method of working: where Evans' work was about capturing private moments unfolding in public, Davidson's subjects are aware and oftentimes posing for the camera. This raises some interesting questions – do we stand to learn more about a person from their conscious or unconscious behavior? Can photos like Davidson's truly be called “documentary,” or do they constitute a different kind of portraiture?

As a whole, the Aperture exhibition doesn't commit any major sins; the photos, presented in vivid dye transfer color prints, look great, and the selection captures the balance of roughness and lyricism for which the series is celebrated. In the end, though, it's a superfluous offering: Davidson is a book photographer, and seeing these images outside of that context does little to enhance our understanding or appreciation of them. Realistically, anyone interested in (re-)discovering this work would be better off spending time with a copy of the new edition of the monograph, which looks just as good and offers the added benefit of purposeful sequencing and a series of essays that illuminate Davidson's objectives, experiences, and working methods.

One question remains, though: Why resurrect this work at this time? My sense is that the decision to re-publish Subway has more to do with the book's turning 25 than with arguing for its relevance to contemporary discourse. As much as I admire Davidson’s series, the truth is that it's hard to find a place for it in today's “photography-about-photography” landscape. Implicit in Subway, after all, is an affirmation of the fidelity of the photographic image. Today, that confidence has been shaken by a proliferation of images and the implications of digital manipulation, resulting in work that compels us to look with new eyes at both the materiality and the function of the photograph. Furthermore, where Davidson's search for meaning led him to venture out into the city, these current trends have brought with them a widespread reinvestment in studio practice. Sure, revisiting 1980s New York is an interesting, even exciting exercise; and yes, as an anomaly in both Davidson's career and the lineage of transit photography, Subway is worth discussing. My feeling, however, is that Aperture's gallery walls would be put to better use presenting fresh work that speaks to the present rather than the past.

Comments on this entry are closed.