Game Plan, MoMA’s retrospective of Alighiero Boetti, splices the Italian artist in two: there was the rabidly sarcastic pop-conceptual artist of the 1960s and the introspective dreamer of the 1970s onward who made big, furry wall hangings. Both of these Boettis produced a lot of art: Game Plan consists of hundreds of works produced from the 1960s through the 1990s and takes up room on two floors of MoMA and part of the sculpture garden.

Boetti started off his career on strong, if imperfect, footing, and like Piero Manzoni before him—the Italian artist who, in 1961, canned his own shit—he had flashes of sarcasm aimed at Anglophone pop and conceptual art. Later in Boetti’s life, the dreamer took over. The works became overly cryptic, based on personal systems and mythology, and they lost some of the playfulness associated with his earlier work.

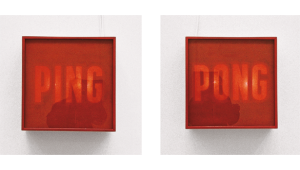

The show opens before you get to the main gallery: two lightboxes surround the doorway, one reading “ping,” the other, “pong,” and they flash on and off, one after the other. It’s a silly, maybe even dumb way to say, “Hey, these are really similar!” But it’s easy to see how Ping Pong (1966) pulls off a casual idea of order—these two things are alike, but different. This isn’t his best work, but it’s kind of funny. Just a wink’s distance away, Boetti’s photograph Twins (1968) has been blown up to fill the entire wall, and shows a subtle game of play with “spot the difference.” Boetti holds hands with someone who looks just like him, but you can’t tell if he’s playing a joke on you. Since when did the artist get a sibling, and a twin no less? It’s not like black and white photos, in all their graininess, can be trusted for accuracy, either.

That idea of deceptive surfaces takes hold in other works from this period, like Cube (1967) and Rosso Gilera 60 1232/Rosso Guzzi 60 1305 (1967). Cube is a big hunk of clear Plexiglas packed full of scraps of wood, steel, rubber, cardboard, glass, wool, and wire. It replaces the grandeur of American minimalism with the raw and imperfect, making something a tad bit more interesting to look at than an ordinary Minimalist cube. In Rosso Gilera 60 1232/Rosso Guzzi 60 1305, Boetti made two red paintings, each named after the industrial paint used on Gilera and Guzzi brand motorcycles. This is pop: it makes plain that commercial industry now dictates how we see the colors of the world. That red is no longer cherry red, but motorcycle red.

By the 1970s, Boetti left behind his playful attitude with surfaces and opposites. If Boetti had invented a twin in 1968, then a decade later, Boetti had become that imaginary twin, and left his former self far behind. In his artistic persona, Boetti transformed into a dreamer, interested in creating complex visual systems. In his personal life, he turned into a kind of art world deadbeat, spending years hanging out in Afghanistan; and he even started a business out there, the One Hotel in Kabul.

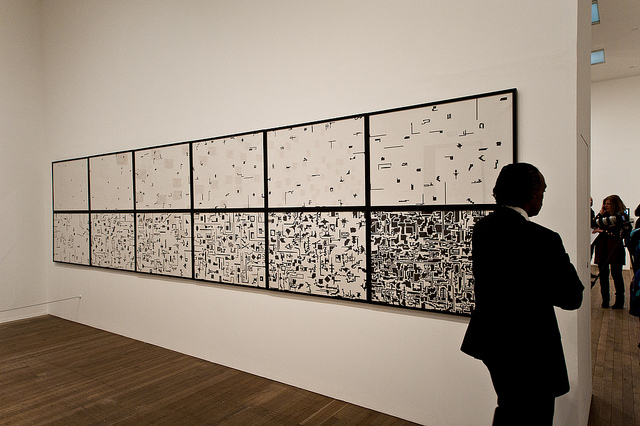

On the 6th floor, many of Boetti’s most visually compelling works were created during this period. There’s some vibrantly colored, large-scale embroideries that looked like blurry landscapes, and some that, oddly, look like a whole lot of QR codes. Natural History of Multiplication (1975) falls into the latter category.

It’s a series of black-and-white drawings on graph paper that show a digital awareness, like they could’ve been made within the last few years. While this, and all the other works in this show that contain QR codes, look really cool, it’s too bad that this “history” is so darn cryptic: it’s not clear how each of the shapes perform multiplication with each other. MoMA lets Boetti speak to this obvious line of questioning with some lines of text on the gallery walls: “It’s just a question of knowing the rules of the game. Someone who doesn’t know them will never see the order that reigns in things.” This sounds like a whiny excuse; it can’t be so hard to let people know what your art’s about.

It’s not just Boetti’s cryptic systems that cause trouble in this exhibition; his personalizing tone makes his works unrelatable to anyone other than himself. When I saw two bronze squares with December 16, 2040, and July 11, 2023 inscribed into them, I laughed, thinking Boetti was making fun of On Kawara’s date paintings, which always take place in the present. That’s not really what Boetti was thinking about with these works: the dates were of mythical importance to Boetti, who needed to publicize in bronze the dates of his imagined death and the hundredth anniversary of his birth. He also made a wall-rug with these dates.

By the time the exhibition reaches the 1990s, Boetti’s continued obsession with that special someone in his life—himself—takes on an even grander scale. One of the more recent works in the exhibition, Orne (Footprints) (1990), was made for the 1990 Venice Biennale. Boetti was selected to represent Italy at the biennale, and this work reflects the sheer excitement of that honor. In it, news articles celebrating the artist’s appointment to the biennale surround the artist’s footprints. It sure is nice to be famous and all, but geez, go get a room with yourself. No doubt about it, this is the essence of self-absorbed navel-gazing.

Boetti must have known his me-centric art practice was becoming a joke. Placed inside MoMA’s sculpture garden, Boetti’s bronze Self-Portrait [My Brain is Smoking] (1993), is so absurd that it makes all the other sculptures hanging out in the grass and concrete seem like the bores of the party. It shows Boetti, fully clad in a suit, dousing himself with a waterhose, but there’s an added trick: inside the sculpture’s head, there’s a heated motor, making it so sizzling hot that the water turns into steam. You know that Yosemite Sam cartoon with steam coming out of its ears? That’s Boetti. The artist is obviously poking fun at himself here, and it’s good to see that he still had a sense of humor this late in his career. It’s too bad this glimmer of sarcasm came back so late because he never had time to develop the third, and last Boetti: the clown.

{ 3 comments }

good review, nice thoughts–looks like a nice show. i like personal systems and am often disappointed when someone with them gives in to requests for more clarity [at least within the art]. to each his/her own.

re: “It can’t be so hard to let people know what your art’s about.” As if that is the imperative? Or you think it should have been/be? Let the dude e dude do his thing. The dude who “lets me know” what his art is “about”, is the bore of the party… Like you said, this is not Alighiero e Boetti.

What’s amazing about art is how many interpretations a work can have. However, you need to have some sense, even a teensy bit, of what the artist’s doing in order to form any sort of reaction. When it comes to systems-based work, an already didactic form implying, “This is the way things are,” then there’s very little room for any interpretation whatsoever. When a system’s off, that leaves no way to get into the work.

Comments on this entry are closed.