Of all the warehouses-turned-art spaces, the Johnson Trading Gallery‘s 1940’s cinema in Queens is pretty cool. Through the back door (unmarked, of course), one enters a black-and-white painted concrete showroom filled with design masterworks spilling upstairs into the projection room (now, an office), a converted lounge, and a cavernous basement. “I found it on Craigslist,” founder Paul Johnson told me last night on the phone. It’s a gem.

The gallery’s well-known in the design world as a late Greenwich Village staple and a regular at the fairs; it just opened an outpost in LA. I first heard of it through a friend in furniture who’d been a fan of the designers and started working for Johnson soon after moving to New York.

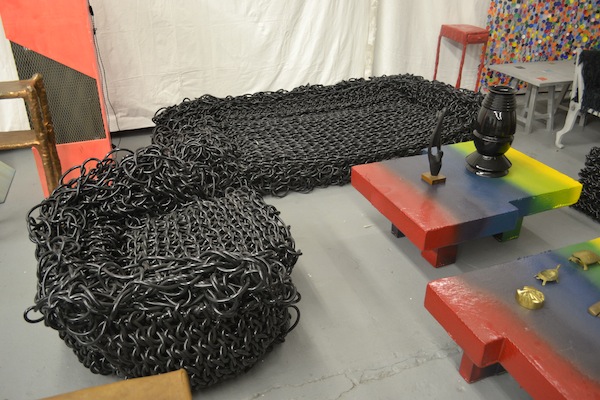

For those of us whose furniture showroom experience is strictly visual, the space is practically a safari of 20th century design. You’ll find, for example, a Frank Lloyd Wright next to pieces by young designers Max Lamb and Kwangho Lee. You’ve got crystalline chairs by architects Aranda/Lasch, a hexagonal wooden table by Frank Lloyd Wright, and a hulking blue chest with the silhouette of an 8-bit space invader by Rafael de Cárdenas. Many of them invite touch and play, like the shaggy wool and fur cushions on Ricky Clifton’s metal seats and Valic’s kangaroo pull toy. There’s even a 10-foot-tall fort by Max Lamb, what looks like a black monolith made of rubber-glazed styrofoam; he’s carved a ladder inside, with a seat and a look-out hole at the top. Robert Loughlin’s signature “The Brute” face is stamped on chairs and tables throughout the gallery.

I want to live here, so I asked founder Paul Johnson a few questions about the showroom.

Clockwise from left: Frank Lloyd Wright nesting table, wood and black hexagonal table by Rafael de Cárdenas, rubber-coated styrofoam vase and stool by Max Lamb

I was wondering if you wouldn’t mind telling me a little bit about how you choose work? There’s a definite sensibility there, everything kind of feels very natural in a weird way.

I’ve been really careful with the designers I’ve worked with, I think. Their sensibility of what furniture is– it’s all very personal to each one of them. They put their own stamp on the work. Even with vintage, I always was attracted to people who made work that was more of a personal thing, less about what was happening at the time; they broke away from trends. Repeatedly, the designers I’ve worked with have been in a situation where they haven’t been able to produce what they wanted to for their clients. They didn’t have an audience for it, so I kind of gave them an audience to do it.

Putting your own stamp on the work makes me think about Robert Loughlin, obviously. [Loughlin was a late famed furniture-picker who marked his own collection by painting a character “The Brute,” a stern, big-jawed man smoking a cigarette, on chairs, tables, mirrors, clothing—just about everything.]

[Paul laughs.]

Did you first meet him through furniture picking or as an artist?

The first time I ever sold a piece of furniture was in October 2000. I had gone to Montreal, bought a bunch of vintage furniture, and basically just rolled up to the flea market in a sixties wood truck. The first person waiting on the back of the truck was Robert.

He was out there as a picker every single week. Even within that first year, I knew that he was kind of this legendary character who had sold furniture to Warhol and Basquiat, all these people. He was at the flea market at three in the morning every Saturday for thirty years.

One day, I was at a store 280 Modern on Lafayette street, and I saw a chair painted with the cigarette guy. I asked what it was, but it wasn’t until six months later that I put two and two together.

You were interested in the work separately?

Yeah, and then I realized it was the same guy I was seeing at the flea market. One time I saw a painting in the back of his truck, and I asked him where he got it. He started laughing, and he said, “What you mean, I paint that!” I traded him something for it, and every week for the next seven years, I’d buy one or two. I’d get to the flea market at two in the morning, I’d shoot the shit with Robert for an hour, buy a painting or two, and then go ahead shopping. It was my reason to get up that early. There were a couple of people who bought them, too, but not as religiously as me, I guess.

He was very knowledgeable about art. Obviously about furniture because he’d been doing it for a long time, but his [understanding of] art was incredible.

Unfortunately, the main part of the Chelsea flea market ended in 2006, when they sold the parking lots for the condos. Everyone kind of stopped going. It used to be huge. When it ended, I didn’t see Robert as much as before. Once in a while, he’d come by my Bond Street gallery, but the mass of it I bought at the market.

So are you still vintage shopping?

Yeah, of course. Vintage shopping is more of a hunting and gathering sort of thing, people tell me what they want, and I go get it. The vintage market’s changed a lot. The prices are leveled, but the internet has leveled the playing field; before, if you were a gallery in New York, you could buy from a guy in Kansas who didn’t have access to the same types of clients. But now you go online, and if the guy’s got a warehouse in the middle of Kansas, he’s going to price it the same as me. It changed the whole thing, for everything. It’s not just that it’s more competitive, but it’s also harder to find more untapped designers.

You’ve discovered a couple of people, like Max Lamb, Kwangho Lee, Paul Evans…

Those are the contemporary ones. Basically, their work resembles the Paul Evans model. He was working in the sixties and seventies, but he had a small studio, he showed with a few people in New York, ended up in people’s homes so he went there and commissioned something. When I started dealing with contemporary design, I found designers working in that mold.

It seems a lot of your designers are people who’ve dabbled in the art world or are kind of connected. Do you see the two as coming closer together, or do you think that’s something that has always been that way?

I think it’s always been like that. If people collect art, then they get the aesthetic of design.

Adam Lindemann was my first big client. This was when I was on 39th street in a tiny studio, and he found me through a friend. He had an empty house that he needed furnishing for a shoot. He was a big first supporter of Paul Evans. We worked on that market together; I ran around the country to find his work.

I fell into the art world crowd, and I guess I always was a big fan of art, I followed the art world, and I think my aesthetic tends to go along with it, or what’s happening. I’ve done Art Basel Miami and Switzerland almost seven years now, so I’ve been around people who are interested in art.

Yes, several of these pieces seem to push the boundaries of what furniture is–the Loughlin paintings, that Max Lamb fort, the crazy, sculptural chair by [architects] Aranda/Lasch.

I think there’s something to be said about architects in furniture today. In the past, they were much more closely connected. van der Rohe would design a building, and then he’d design all the furniture inside. Philip Johnson, any of those guys. Today it doesn’t really work like that. There’s a boundary between outside and inside…I’m kind of tired of that argument, though. Architects can design furniture, too, people just don’t trust them like they used to.

{ 1 comment }

what a bunch of junk

Comments on this entry are closed.